Volume 28, Number 7—July 2022

Dispatch

Determining Infected Aortic Aneurysm Treatment Using Focused Detection of Helicobacter cinaedi

Cite This Article

Citation for Media

Abstract

We detected Helicobacter cinaedi in 4 of 10 patients with infected aortic aneurysms diagnosed using blood or tissue culture in Aichi, Japan, during September 2017–January 2021. Infected aortic aneurysms caused by H. cinaedi had a higher detection rate and better results after treatment than previously reported, without recurrent infection.

Infected aortic aneurysms account for 0.7%–3% of all aortic aneurysms and are associated with a 26%–44% mortality rate (1). No consensus exists about appropriate antimicrobial therapy and treatment duration for infected aneurysms. Moreover, determining surgical treatment in each case requires carefully considering the causative bacterium and the patient’s medical background (2). Recently, several cases of infected aortic aneurysms caused by Helicobacter cinaedi, a rare, difficult-to-detect causative bacterium have been reported (3).

First identified in 1984, H. cinaedi, a gram-negative rod with spiral morphology and bipolar flagella, is indigenous to the intestinal tract of humans and other animals (4,5). This bacterium produces a cytolethal distending toxin that invades epithelial cells (6) and is associated with bacteremia in compromised hosts and infected aortic aneurysms, mediated by bacterial translocation from the intestinal mucosa (7,8). Because of the high recurrence rate for H. cinaedi bacteremia, it is recommended that patients receive prolonged treatment of at least 3 months with appropriate antimicrobial drugs (9). We sought to determine the efficacy of treatment for infected aortic aneurysms through the focused detection of H. cinaedi.

During September 2017–January 2021, we treated 10 patients with infected aortic aneurysms from a single center in Aichi, Japan. Diagnosis, including for recurrent aneurysms, was based on either positive culture or PCR of aortic tissue resected at the time of surgery or positive blood or puncture culture of an abscess caused by a hematogenous infection in patients who did not undergo open surgery and had clinical findings localized to the aortic aneurysm.

We started patients on antimicrobial therapy with meropenem when H. cinaedi was suspected or gram-negative rods were identified, then changed to sulbactam/ampicillin after confirming drug sensitivity. After 4 weeks of treatment or a negative inflammatory reaction, the antimicrobial treatment was switched to minocycline or amoxicillin/clavulanate for 3–6 months. If other causative bacteria were identified, antimicrobial drugs were changed based on drug sensitivity results and continued for 3–6 months. Rifampin-soaked graft replacement was the first-choice surgical treatment, irrespective of causative bacterium.

Among the 10 patients with infected aortic aneurysms, H. cinaedi was the causative bacterium in 4, Staphylococcus aureus in 3, Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis in 1, and Enterobacter cloacae in 1. Treatment included vascular replacement in 7 patients (2 with H. cinaedi), endovascular stent grafting in 1 (with H. cinaedi), and medical treatment in 2 patients (1 with H. cinaedi). One patient with aortic rupture and Salmonella Enteritidis infection died postoperatively from multiorgan failure; the other 9 patients had good courses of recovery without recurrence (Table 1).

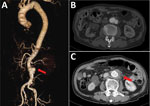

All 4 of the H. cinaedi–infected case-patients were immunocompromised (diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease, cancer). However, their clinical findings were mild, and C-reactive protein levels tended to be low (H. cinaedi/non–H. cinaedi median 4.3/21.6 mg/dL) at hospital admission. All patients had saccular aneurysms and severely calcified aortas. Surgical findings showed highly adherent areas around the aneurysms with intimal defects but without abscess formation. Pathological examination revealed severe lymphocytic infiltration in the aneurysmal wall with loss of elastic fibers. In contrast, 3 of 5 patients in the non–H. cinaedi group showed abscesses and hematomas around the infections (Figure 1).

We performed blood cultures using the BacT/Alert system (bioMérieux, https://www.biomerieux.com) and grew microaerobic cultures in the presence of hydrogen using a commercial hydrogen generator (SUGIYAMA-GEN Co., Ltd., http://sugiyama-gen.com). In the H. cinaedi group, we used multilocus sequence typing (MLST) to identify the subtype, and we immunostained aortic tissues with antiserum against the whole-cell lysate of H. cinaedi raised in rabbits (Figure 2; Appendix Figure) (10).

Among the H. cinaedi patients, we were able to subculture isolates from 3; the range of blood culture growth times, 75.3–160.8 h (median 90.6 h), was longer than that among the non–H. cinaedi patients, 12.3–28.3 h (median 12.3 h). Drug susceptibility testing demonstrated levofloxacin-resistant H. cinaedi, although the sequence type on MLST was different in each case (Tables 1, 2).

Infected aortic aneurysms caused by H. cinaedi are increasingly being recognized, especially in Japan, although the detection rate remains low (3). One study reported 734 cases of infected aortic aneurysms caused by various organisms, including Salmonella, Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, and Escherichia coli, but not H. cinaedi (1). Infected aortic aneurysms are a critical disease with high mortality, and whereas identifying the causative bacteria is effective in determining treatment, 23.3%–25% of cases are caused by unidentified bacteria (1). In our study, the detection rate for H. cinaedi in infected aortic aneurysms was high, 40%, although the absolute number of cases was small. Of note, infections caused by H. cinaedi all showed good clinical courses. H. cinaedi is known to cause nosocomial infections; however, nosocomial infections were ruled out as mode of infection here because the 3 isolates that underwent MLST had different sequence types (11).

The Bactec FX system (https://www.bd.com), widely used for blood culturing of H. cinaedi, is generally considered to be more sensitive than the bioMérieux BacT/Alert system (8). Nevertheless, by assuming H. cinaedi was the causative bacterium of the infected aortic aneurysms for our patients and simply allowing a longer incubation period of 10 days versus the usual 5 days, the BacT/Alert system detected the bacterium in 3/4 cases, comparable to the Bactec FX system (12). It is sometimes difficult to grow bacterial subcultures in microaerophilic conditions; however, adding 5%–10% hydrogen effectively helps form characteristic thin-spread colonies (4). PCR reliably detects and identifies species, but matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry is also useful (13), although unfortunately this testing method results in a time lag between initiating treatment on and identifying bacteria.

H. cinaedi infects atherosclerotic sites, leading to the progression of atherosclerosis through lipid accumulation (5,14). Progression is slow, often taking months, and leads to no clinical findings even if a local infection is established (7,15). Considering the slow, localized progression and difficulty of detection of atherosclerosis associated with H. cinaedi infection, aortic aneurysms thought to be noninfectious might actually be infected by H. cinaedi. Clarifying the relationship between this bacterium and atherosclerotic diseases might lead to additional treatments.

No infected aortic aneurysms caused by H. cinaedi have resulted in rupture, and cases usually pass without recurrence following an appropriate period of antibiotic treatment. Because nonsurgical treatment has been shown to be effective, open surgery during the acute phase of infection might be overindicated. Endovascular stent grafting, a less invasive treatment than the standard vascular replacement procedure, followed by use of appropriate antimicrobial agents might successfully complete treatment (3). This treatment is beneficial among aging patients, and it is hoped that the presence of these bacteria in infected aortic aneurysms will be widely recognized, with treatment and diagnosis proceeding simultaneously.

In summary, although H. cinaedi is a relatively rare cause of infected aortic aneurysms, it might be overlooked because of its low initial detection rate. Detection during treatment initiation can improve patient life expectancy by enabling effective antimicrobial therapy and expanding treatment options.

Dr. Saito is a researcher in the Department of Cardiovascular Surgery at Nagoya City University. His main research interests include Helicobacter cinaedi infections and arteriosclerosis.

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Asano for the useful discussions and careful proofreading of the manuscript and Tuge Kaori, Okaniwa Izumi, and Tsukamoto Haruka for helping us cultivate the bacteria. We also thank Editage for English language editing.

This work was supported by Japan Society for the Promotion of Science Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (KAKENHI) grant no. JP16K18928 and Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED) under grant no. JP20fk0108148j0001.

References

- Sörelius K, Budtz-Lilly J, Mani K, Wanhainen A. Systematic review of the management of mycotic aortic aneurysms. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2019;58:426–35. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Lee CH, Hsieh HC, Ko PJ, Li HJ, Kao TC, Yu SY. In situ versus extra-anatomic reconstruction for primary infected infrarenal abdominal aortic aneurysms. J Vasc Surg. 2011;54:64–70. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Matsuo T, Mori N, Mizuno A, Sakurai A, Kawai F, Starkey J, et al. Infected aortic aneurysm caused by Helicobacter cinaedi: case series and systematic review of the literature. BMC Infect Dis. 2020;20:854. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Fennell CL, Totten PA, Quinn TC, Patton DL, Holmes KK, Stamm WE. Characterization of Campylobacter-like organisms isolated from homosexual men. J Infect Dis. 1984;149:58–66. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Kawamura Y, Tomida J, Morita Y, Fujii S, Okamoto T, Akaike T. Clinical and bacteriological characteristics of Helicobacter cinaedi infection. J Infect Chemother. 2014;20:517–26. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Taylor NS, Ge Z, Shen Z, Dewhirst FE, Fox JG. Cytolethal distending toxin: a potential virulence factor for Helicobacter cinaedi. J Infect Dis. 2003;188:1892–7. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Kushimoto K, Yonekura R, Umesue M, Oshiro Y, Yamasaki H, Yoshida K, et al. Infected thoracic aortic aneurysm caused by Helicobacter cinaedi. Ann Vasc Dis. 2017;10:139–42. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Araoka H, Baba M, Okada C, Kimura M, Sato T, Yatomi Y, et al. First evidence of bacterial translocation from the intestinal tract as a route of Helicobacter cinaedi bacteremia. Helicobacter. 2018;23:

e12458 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Araoka H, Baba M, Kimura M, Abe M, Inagawa H, Yoneyama A. Clinical characteristics of bacteremia caused by Helicobacter cinaedi and time required for blood cultures to become positive. J Clin Microbiol. 2014;52:1519–22. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Rimbara E, Mori S, Matsui M, Suzuki S, Wachino J, Kawamura Y, et al. Molecular epidemiologic analysis and antimicrobial resistance of Helicobacter cinaedi isolated from seven hospitals in Japan. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50:2553–60. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Rimbara E, Mori S, Kim H, Matsui M, Suzuki S, Takahashi S, et al. Helicobacter cinaedi and Helicobacter fennelliae transmission in a hospital from 2008 to 2012. J Clin Microbiol. 2013;51:2439–42. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Miyake N, Chong Y, Nishida R, Nagasaki Y, Kibe Y, Kiyosuke M, et al. A dramatic increase in the positive blood culture rates of Helicobacter cinaedi: the evidence of differential detection abilities between the Bactec and BacT/Alert systems. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2015;83:232–3. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Taniguchi T, Sekiya A, Higa M, Saeki Y, Umeki K, Okayama A, et al. Rapid identification and subtyping of Helicobacter cinaedi strains by intact-cell mass spectrometry profiling with the use of matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry. J Clin Microbiol. 2014;52:95–102. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Khan S, Okamoto T, Enomoto K, Sakashita N, Oyama K, Fujii S, et al. Potential association of Helicobacter cinaedi with atrial arrhythmias and atherosclerosis. Microbiol Immunol. 2012;56:145–54. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Oyama K, Khan S, Okamoto T, Fujii S, Ono K, Matsunaga T, et al. Identification of and screening for human Helicobacter cinaedi infections and carriers via nested PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50:3893–900. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

Figures

Tables

Cite This ArticleOriginal Publication Date: June 09, 2022

Table of Contents – Volume 28, Number 7—July 2022

| EID Search Options |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Please use the form below to submit correspondence to the authors or contact them at the following address:

Saito Jien, Department of Cardiovascular Surgery, Nagoya City University East Medical Center, 1-2-23 Wakamizu, Chikusa-ku, Nagoya, Aichi, 464-8547, Japan

Top