Fatal Human Neurologic Infection Caused by Pigeon Avian Paramyxovirus-1, Australia

Siobhan Hurley

1

, John Sebastian Eden

1, John Bingham, Michael Rodriguez, Matthew J. Neave, Alexandra Johnson, Annaleise R. Howard-Jones, Jen Kok, Antoinette Anazodo, Brendan McMullan, David T. Williams, James Watson, Annalisa Solinas, Ki Wook Kim

2, and William Rawlinson

2

Author affiliations: Prince of Wales Hospital, Randwick, New South Wales, Australia (S. Hurley, K.W. Kim); Westmead Institute for Medical Research Centre for Virus Research, Westmead, New South Wales, Australia (J.S. Eden); Sydney Institute for Infectious Diseases, University of Sydney Faculty of Medicine and Health, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia (J.S. Eden, A.R. Howard-Jones); CSIRO Australian Centre for Disease Preparedness, Geelong, Victoria, Australia (J. Bingham, M.J. Neave, D.T. Williams, J. Watson); Prince of Wales and Sydney Children’s Hospital, Randwick (M. Rodriguez, A. Solinas); Sydney Children’s Hospital, Randwick (A. Johnson, B. McMullan); Centre for Infectious Diseases and Microbiology Laboratory Services, New South Wales Health Pathology–Institute of Clinical Pathology and Medical Research, Westmead (A.R. Howard-Jones, J. Kok); Kids Cancer Centre, Sydney Children’s Hospital, Randwick (A. Anazodo); University of New South Wales Faculty of Medicine and Health, School of Clinical Medicine, Sydney (B. McMullan, K. Kim); Prince of Wales Hospital and Community Health Services, Sydney (W. Rawlinson); University of New South Wales Schools of Clinical Medicine, Biotechnology and Biomolecular Sciences, Sydney (W. Rawlinson)

Main Article

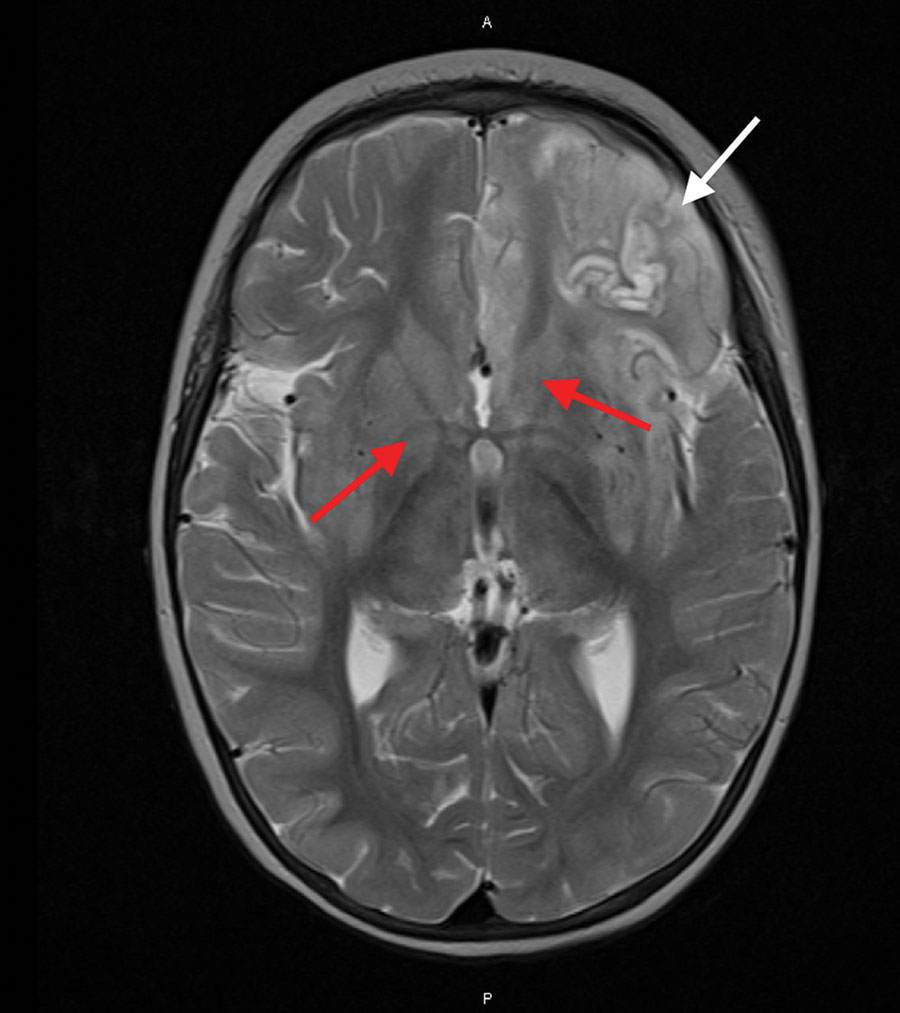

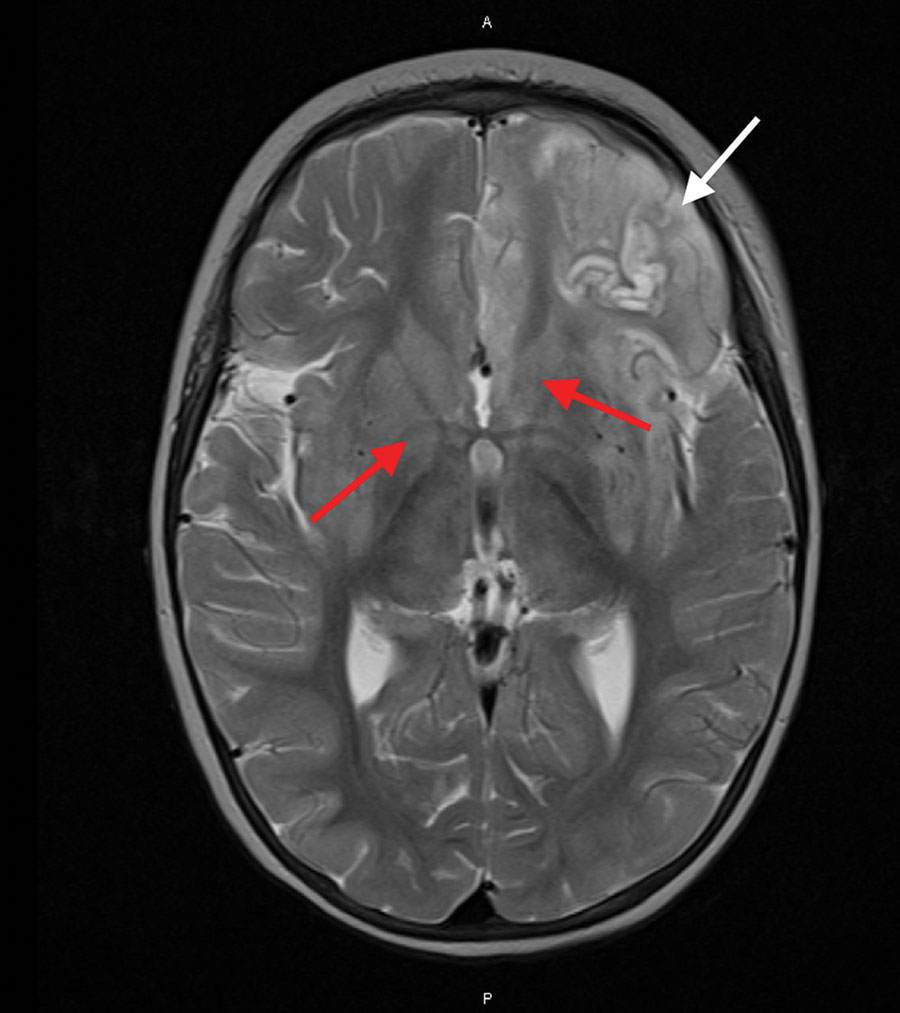

Figure 2

Figure 2. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain of an immunocompromised child with avian paramyxovirus type 1 infection, Australia. Image, captured 16 days after hospital admission, shows predominantly left frontal and insular T2 signal hyperintensity evolving into laminar necrosis (white arrow) and hyperintensity of deep gray-matter structures (red arrows).

Main Article

Page created: November 13, 2023

Page updated: November 18, 2023

Page reviewed: November 18, 2023

The conclusions, findings, and opinions expressed by authors contributing to this journal do not necessarily reflect the official position of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the Public Health Service, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or the authors' affiliated institutions. Use of trade names is for identification only and does not imply endorsement by any of the groups named above.