Volume 29, Number 6—June 2023

Research Letter

Manifestations and Management of Trimethoprim/Sulfamethoxazole–Resistant Nocardia otitidiscaviarum Infection

Cite This Article

Citation for Media

Abstract

Nocardia can cause systemic infections with varying manifestations. Resistance patterns vary by species. We describe N. otitidiscavarium infection with pulmonary and cutaneous manifestations in a man in the United States. He received multidrug treatment that included trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole but died. Our case highlights the need to treat with combination therapy until drug susceptibilities are known.

Nocardia otitidiscaviarum was first described in 1924 after being isolated from a guinea pig with ear disease (1). N. otitidiscaviarum infections account for ≈5.9% of all Nocardia infections (2,3). Nocardia can cause systemic infections with varying clinical signs. Predisposing factors are chronic lung disease, corticosteroid use, HIV infection, solid organ transplant, and solid organ malignancy (4). Patterns of resistance to antimicrobial therapies vary widely among Nocardia species. We present a case of a man with pulmonary and cutaneous manifestations of a trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (TMP/SMX)–resistant N. otitidiscaviarum infection.

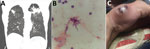

The patent was a 73-year-old man in Gainesville, Florida, USA, who had severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, coronary artery disease, and congestive heart failure. In June 2020, he sought care for fever, productive cough, dyspnea on exertion, and a 30-pound weight loss over 4 months. Six months earlier, he had undergone computed tomography (CT) of the chest because of his smoking history and concern for unintentional weight loss. Scans revealed a 3.4-cm spiculated, cavitary, right upper lobe mass with associated precarinal and right hilar adenopathy. Subsequent positron emission tomography/CT showed a hypermetabolic wedge-shaped subpleural area of consolidation (5.0 × 4.1 cm) in the right upper lobe, consistent with pneumonia. Antimicrobial drugs were administered. Follow-up CT chest 3 months later showed progressive disease bilaterally in the upper lobes (Figure, panel A). The patient was then hospitalized and underwent bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL). We sent cultures for bacterial, including mycobacterial, and fungal testing. Pending results of the BAL gram stain and cultures, we empirically prescribed broad-spectrum antimicrobial drugs (i.e., vancomycin, cefepime, and metronidazole) for pneumonia, and the patient was discharged after clinical improvement. The BAL sample showed gram-positive branching rods (Figure, panel B), and N. otitidiscaviarum grew on culture. The patient was readmitted to the hospital.

At readmission, examination was remarkable for distant heart and lung sounds and a prolonged expiratory phase. The patient had no noticeable skin lesions at that time. CT of the head with contrast (implantable cardioverter device was not compatible with magnetic resonance imaging) revealed no focal enhancing lesions. We empirically started intravenous TMP/SMX, intravenous amikacin, and oral levofloxacin. At the same time, the patient discovered a rapidly enlarging skin lesion along the ulnar aspect of the right hand (Figure, panel C). We incised and drained the 2.5-cm abscess, and N. otitidiscaviarum grew in cultures with broth microdilution. On the basis of sensitivity results (Table), we discontinued TMP/SMX and levofloxacin and added linezolid and clarithromycin; amikacin remained unchanged. Unfortunately, acute renal injury developed, and a new, prolonged QTc interval was seen on electrocardiogram. Those findings were attributed to either amikacin or clarithromycin, which prompted discontinuation of the aminoglycoside and macrolide. Repeat CT of the chest at week 6 of treatment showed disease progression. The patient subsequently decided to pursue palliative care and subsequently died.

Clinical manifestations of N. otitidiscaviarum infection may include pneumonia, brain abscess, lung abscess, skin abscess, muscle abscess, ocular infections, bacteremia, osteomyelitis, and septic joints (4). The risk factor for this patient was chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. The patient had pulmonary involvement and a rapidly developing skin abscess.

Antimicrobial drug resistance of N. otitidiscaviarum is variable. The organism is usually sensitive to linezolid, amikacin, TMP/SMX, doxycycline, gentamicin, and minocycline. Susceptibility to carbapenems is limited; most activity is from imipenem compared with meropenem or ertapenem. N. otitidiscaviarum is generally resistant to amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, cefotaxime, ceftriaxone, ciprofloxacin, moxifloxacin, tobramycin, and clarithromycin (3–5).

This case demonstrates the value of considering Nocardia infection for patients with cavitary lung disease and concomitant soft tissue abscesses. It also highlights the need to choose appropriate initial antimicrobial therapy. In the absence of a drug susceptibility profile, clinicians should approach the selection of antibiotics with a framework that considers disease severity, the epidemiologic probability of particular species, and the most likely resistance profiles of the species. Treatment can be narrowed after the species and susceptibilities are known.

Dr. Fu is an internal medicine resident at the University of Florida, pursuing a fellowship in pulmonology and critical care. Her research interests include global health, clinical education, pulmonary diseases, critical care, and pulmonary hypertension.

References

- Brown-Elliott BA, Brown JM, Conville PS, Wallace RJ Jr. Clinical and laboratory features of the Nocardia spp. based on current molecular taxonomy. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2006;19:259–82. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Tan C-K, Lai C-C, Lin S-H, Liao CH, Chou CH, Hsu HL, et al. Clinical and microbiological characteristics of Nocardiosis including those caused by emerging Nocardia species in Taiwan, 1998-2008. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2010;16:966–72. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Wang H, Zhu Y, Cui Q, Wu W, Li G, Chen D, et al. Epidemiology and antimicrobial resistance profiles of the Nocardia species in China, 2009–2021. Microbiol Spectr. 2022;10:

e0156021 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Brown-Elliott BA, Killingley J, Vasireddy S, Bridge L, Wallace RJ Jr. In vitro comparison of ertapenem, meropenem, and imipenem against isolates of rapidly growing mycobacteria and Nocardia by use of broth microdilution and Etest. J Clin Microbiol. 2016;54:1586–92. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

Figure

Table

Cite This ArticleOriginal Publication Date: April 24, 2023

Table of Contents – Volume 29, Number 6—June 2023

| EID Search Options |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Please use the form below to submit correspondence to the authors or contact them at the following address:

Katherine Fu, Department of Medicine, University of Florida College of Medicine, 1600 SW Archer Rd, Gainesville, FL 32610, USA

Top