Volume 30, Number 12—December 2024

Online Report

Operational Risk Assessment Tool for Evaluating Leishmania infantum Introduction and Establishment in the United States through Dog Importation1

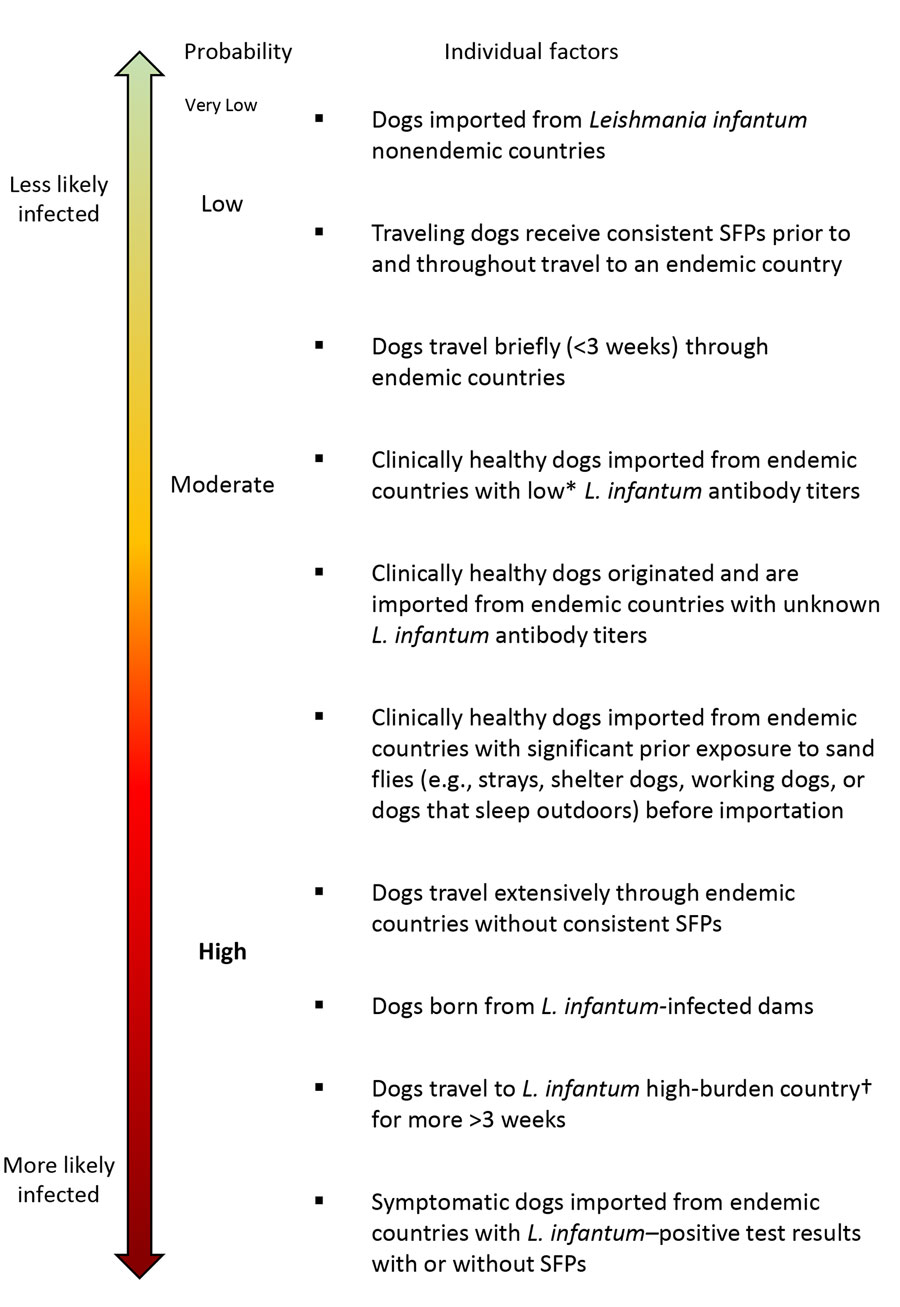

Figure 5

Figure 5. Probability scale used to develop an operational risk assessment tool for evaluating Leishmania infantum introduction and establishment in the United States through dog importation. *Negative serologic titers are typically those <1:40, but titer thresholds vary by laboratory. Titer values 1–2-fold higher than reference thresholds should be considered low titers and values >2-fold the reference should be considered a high titer (45). †Endemic and high burden countries are listed elsewhere (Appendix). SFPs, sand fly preventatives.

References

- Wright I, Jongejan F, Marcondes M, Peregrine A, Baneth G, Bourdeau P, et al. Parasites and vector-borne diseases disseminated by rehomed dogs. Parasit Vectors. 2020;13:546. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- McQuiston JH, Wilson T, Harris S, Bacon RM, Shapiro S, Trevino I, et al. Importation of dogs into the United States: risks from rabies and other zoonotic diseases. Zoonoses Public Health. 2008;55:421–6. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Wright I, Whitfield V, Hanaghan R, Upjohn M, Boyden P. Analysis of exotic pathogens found in a large group of imported dogs following an animal welfare investigation. Vet Rec. 2023;193:

e2996 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Guidance regarding agency interpretation of “rabies-free” as it relates to the importation of dogs into the United States. Federal Register. 2019 Jan 31 [cited 2023 May 22]. https://www.federalregister.gov/d/2019-00506

- United States Department of Agriculture. Report on the importation of live dogs into the United States. 2019 Jun 25 [cited 2023 May 22]. http://www.naiaonline.org/uploads/WhitePapers/USDA_DogImportReport6-25-2019.pdf

- Herricks JR, Hotez PJ, Wanga V, Coffeng LE, Haagsma JA, Basáñez MG, et al. The global burden of disease study 2013: What does it mean for the NTDs? PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017;11:

e0005424 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Vilas-Boas DF, Nakasone EKN, Gonçalves AAM, Lair DF, Oliveira DS, Pereira DFS, et al. Global distribution of canine visceral leishmaniasis and the role of the dog in the epidemiology of the disease. Pathogens. 2024;13:455. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Duprey ZH, Steurer FJ, Rooney JA, Kirchhoff LV, Jackson JE, Rowton ED, et al. Canine visceral leishmaniasis, United States and Canada, 2000-2003. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:440–6. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Toepp AJ, Schaut RG, Scott BD, Mathur D, Berens AJ, Petersen CA. Leishmania incidence and prevalence in U.S. hunting hounds maintained via vertical transmission. Vet Parasitol Reg Stud Reports. 2017;10:75–81. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Bruhn FRP, Morais MHF, Cardoso DL, Bruhn NCP, Ferreira F, Rocha CMBMD. Spatial and temporal relationships between human and canine visceral leishmaniases in Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, 2006-2013. Parasit Vectors. 2018;11:372. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- World Health Organization. Leishmaniasis. 2023 Jan 12 [cited 2023 May 22]. https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/leishmaniasis

- Martín-Sánchez J, Morales-Yuste M, Acedo-Sánchez C, Barón S, Díaz V, Morillas-Márquez F. Canine leishmaniasis in southeastern Spain. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:795–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Gin TE, Lashnits E, Wilson JM, Breitschwerdt EB, Qurollo B. Demographics and travel history of imported and autochthonous cases of leishmaniosis in dogs in the United States and Canada, 2006 to 2019. J Vet Intern Med. 2021;35:954–64. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Curtin JM, Aronson NE. Leishmaniasis in the United States: emerging issues in a region of low endemicity. Microorganisms. 2021;9:578. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Operational tool on rapid risk assessment methodology. 2019 Mar 14 [cited 2023 May 22] https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/operational-tool-rapid-risk-assessment-methodolgy-ecdc-2019.pdf

- Wieland B, Dhollander S, Salman M, Koenen F. Qualitative risk assessment in a data-scarce environment: a model to assess the impact of control measures on spread of African Swine Fever. Prev Vet Med. 2011;99:4–14. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- World Health Organization, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, and World Organisation for Animal Health. Joint risk assessment operational tool (JRA OT): an operational tool of the tripartite zoonoses guide. 2021 Mar 9 [cited 2023 May 22]. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240015142

- World Organisation for Animal Health. Handbook on import risk analysis for animals and animal products, 2nd edition. Paris: The Organisation; 2010.

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Technical guidelines on rapid risk assessment for animal health threats. FAO animal production and health guidelines no. 24. Rome: The Organization; 2021.

- Department of Agriculture and Water Resources. Biosecurity import risk analysis guidelines, 2016: managing biosecurity risks for imports into Australia. Canberra: Department of Agriculture and Water Resources; 2016.

- McKenna M, Attipa C, Tasker S, Augusto M. Leishmaniosis in a dog with no travel history outside of the UK. Vet Rec. 2019;184:441. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Toepp AJ, Bennett C, Scott B, Senesac R, Oleson JJ, Petersen CA. Maternal Leishmania infantum infection status has significant impact on leishmaniasis in offspring. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2019;13:

e0007058 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Silva FL, Oliveira RG, Silva TM, Xavier MN, Nascimento EF, Santos RL. Venereal transmission of canine visceral leishmaniasis. Vet Parasitol. 2009;160:55–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Schantz PM, Steurer FJ, Duprey ZH, Kurpel KP, Barr SC, Jackson JE, et al. Autochthonous visceral leishmaniasis in dogs in North America. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2005;226:1316–22. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Naucke TJ, Amelung S, Lorentz S. First report of transmission of canine leishmaniosis through bite wounds from a naturally infected dog in Germany. Parasit Vectors. 2016;9:256. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- McGrotty Y, Kilpatrick S, Magowan D, Colville R. Canine leishmaniosis in a non-travelled dog. Vet Rec. 2023;192:174–6. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Morales-Yuste M, Martín-Sánchez J, Corpas-Lopez V. Canine leishmaniasis: update on epidemiology, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention. Vet Sci. 2022;9:387. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Esch KJ, Petersen CA. Transmission and epidemiology of zoonotic protozoal diseases of companion animals. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2013;26:58–85. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Pereira MA, Santos R, Oliveira R, Costa L, Prata A, Gonçalves V, et al. Prognostic factors and life expectancy in canine leishmaniosis. Vet Sci. 2020;7:128. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Berger BA, Bartlett AH, Saravia NG, Galindo Sevilla N. Pathophysiology of leishmania infection during pregnancy. Trends Parasitol. 2017;33:935–46. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Pineda JA, Martín-Sánchez J, Macías J, Morillas F. Leishmania spp infection in injecting drug users. Lancet. 2002;360:950–1. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Miró G, López-Vélez R. Clinical management of canine leishmaniosis versus human leishmaniasis due to Leishmania infantum: Putting “One Health” principles into practice. Vet Parasitol. 2018;254:151–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Franssen SU, Sanders MJ, Berriman M, Petersen CA, Cotton JA. Geographic origin and vertical transmission of Leishmania infantum parasites in hunting hounds, United States. Emerg Infect Dis. 2022;28:1211–23. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Schaut RG, Robles-Murguia M, Juelsgaard R, Esch KJ, Bartholomay LC, Ramalho-Ortigao M, et al. Vectorborne transmission of Leishmania infantum from hounds, United States. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015;21:2209–12. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Young DG. Phlebotomine sand flies of North America (Diptera: Psychodidae). Mosq News. 1984;44:2.

- McHugh CP, Grogl M, Kreutzer RD. Isolation of Leishmania mexicana (Kinetoplastida: Trypanosomatidae) from Lutzomyia anthophora (Diptera: Psychodidae) collected in Texas. J Med Entomol. 1993;30:631–3. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Beasley EA, Mahachi KG, Petersen CA. Possibility of Leishmania transmission via Lutzomyia spp. sand flies within the USA and implications for human and canine autochthonous infection. Curr Trop Med Rep. 2022;9:160–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Lawyer PG, Young DG. Experimental transmission of Leishmania mexicana to hamsters by bites of phlebotomine sand flies (Diptera: Psychodidae) from the United States. J Med Entomol. 1987;24:458–62. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Endris RG, Young DG, Perkins PV. Experimental transmission of Leishmania mexicana by a North American sand fly, Lutzomyia anthophora (Diptera: Psychodidae). J Med Entomol. 1987;24:243–7. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Lawyer PG, Young DG, Butler JF, Akin DE. Development of Leishmania mexicana in Lutzomyia diabolica and Lutzomyia shannoni (Diptera: Psychodidae). J Med Entomol. 1987;24:347–55. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Travi BL, Ferro C, Cadena H, Montoya-Lerma J, Adler GH. Canine visceral leishmaniasis: dog infectivity to sand flies from non-endemic areas. Res Vet Sci. 2002;72:83–6. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Courtenay O, Peters NC, Rogers ME, Bern C. Combining epidemiology with basic biology of sand flies, parasites, and hosts to inform leishmaniasis transmission dynamics and control. PLoS Pathog. 2017;13:

e1006571 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Scorza BM, Mahachi KG, Cox AC, Toepp AJ, Leal-Lima A, Kumar Kushwaha A, et al. Leishmania infantum xenodiagnosis from vertically infected dogs reveals significant skin tropism. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2021;15:

e0009366 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Paltrinieri S, Solano-Gallego L, Fondati A, Lubas G, Gradoni L, Castagnaro M, et al.; Canine Leishmaniasis Working Group, Italian Society of Veterinarians of Companion Animals. Guidelines for diagnosis and clinical classification of leishmaniasis in dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2010;236:1184–91. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Miró G, Wright I, Michael H, Burton W, Hegarty E, Rodón J, et al. Seropositivity of main vector-borne pathogens in dogs across Europe. Parasit Vectors. 2022;15:189. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Martín-Sánchez J, Rodríguez-Granger J, Morillas-Márquez F, Merino-Espinosa G, Sampedro A, Aliaga L, et al. Leishmaniasis due to Leishmania infantum: Integration of human, animal and environmental data through a One Health approach. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2020;67:2423–34. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Estevam LGTM, Veloso LB, Silva GG, Mori CC, Franco PF, Lima ACVMR, et al. Leishmania infantum infection rate in dogs housed in open-admission shelters is higher than of domiciled dogs in an endemic area of canine visceral leishmaniasis. Epidemiological implications. Acta Trop. 2022;232:

106492 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Hamel D, Silaghi C, Pfister K. Arthropod-borne infections in travelled dogs in Europe. Parasite. 2013;20:9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Teske E, van Knapen F, Beijer EG, Slappendel RJ. Risk of infection with Leishmania spp. in the canine population in the Netherlands. Acta Vet Scand. 2002;43:195–201. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

1Preliminary results from this study were presented at the American Society for Tropical Medicine and Hygiene Annual Meeting; October 18–22, 2023; Chicago, Illinois, USA.

2These first authors contributed equally to this article.

3These senior authors contributed equally to this article.