Volume 30, Number 3—March 2024

Research Letter

Betacoronavirus Infection Outbreak, São Paulo, Brazil, Fall 2023

Cite This Article

Citation for Media

Abstract

We report a human coronavirus OC43 infection outbreak in hospitalized patients and healthcare workers in São Paulo, Brazil, occurring after SARS-CoV-2 cases disappeared. Infection was associated with healthcare workers in 5 (29.4%) patients. Routine surveillance including a respiratory virus panel can improve coronavirus detection in both healthcare professionals and patients.

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused major human and social behavior changes. Human coronavirus (HCoV) OC43, a common human coronavirus, remains a major cause of respiratory infections. HCoV-OC43 can infect humans at any age, causing lower respiratory tract infections that can be severe in patients who have concurrent conditions (1,2). Until May 2023, a total of 2,533 patients were hospitalized with COVID-19 at Hospital São Paulo (São Paulo, Brazil). We report an unexpected HCoV-OC43 infection outbreak among patients and healthcare workers at Hospital São Paulo. We conducted this observational study in compliance with institutional guidelines and approval by the Ethics Committee of Universidade Federal de São Paulo (CEP/UNIFESP no. 29407720.4.00 00.5505).

During March–June 2023 (fall season), we collected swab specimens from patients and screened those specimens for influenza A/B virus, respiratory syncytial virus, SARS-CoV-2, and HCoV in the laboratory at our hospital as a routine surveillance method used since 2020. We evaluated samples from 927 persons who had acute respiratory infections: 446 hospitalized patients and 481 healthcare workers. We detected HCoV by using multiplex real-time PCR with specific primers and probes for HCoV-OC43, HCoV-229E, HCoV-40 HKU-1, and HCoV-NL63 (3,4). Among tested samples, 7.7% (71/927) were positive for HCoV: 10.6% (51/481) for healthcare workers and 4.5% (20/446) for hospitalized patients (Table).

Of the 71 HCoV-positive samples, 28.2% (20/71) were obtained from hospitalized patients (mean age 34.5 years; interquartile range 6–64 years) and 71.8% (51/71) from healthcare workers (mean age 41.9 years; interquartile range 32–52 years). Among healthcare workers, 46 (90.2%) samples were positive for HCoV-OC43, 4 (7.8%) for HCoV-NL63, and 1 (2%) for HCoV-229E. Among hospitalized patients, 16 (80%) patients were positive for OC43, 3 (15%) for NL63, and 1 (5%) for HKU-1. Co-infections were identified in only 4 (5.6%) case-patients: 1 patient had both HCoV-NL63 and SARS-CoV2, 1 patient had both HCoV-OC43 and respiratory syncytial virus, and 2 patients each had both HCoV-OC43 and influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 virus.

All 16 inpatients who had HCoV-OC43 had risk factors for more severe illness, such as immunosuppression (3 patients) and underlying conditions (8 patients); 5 (31.2%) patients had both. Two (2/16; 12.5%) immunosuppressed patients required admission to an intensive care unit and died (1 child, 1 adult).

Radiologic images were obtained for 14 of 16 inpatients who had HCoV-OC43, and 62.5% (10/16) had an alteration detected by chest computed tomography. Radiologic findings included lung opacities, bilateral interstitial infiltrate, consolidations, and centrilobular micronodules with a unifocal or multifocal ground glass pattern, all of which were predominantly distributed within the lower lobes.

A probable nosocomial acquisition might have occurred because the infection rate among healthcare workers peaked earlier (May) than the observed inpatient peak rate (June) (Table). Five (31.2%) inpatients who had HCoV-OC43–positive samples were housed within different wards several days after admission; thus, it was possible to confirm nosocomial acquisition. In those cases, HCoV-OC43 transmission took place within inpatient wards, specifically during activities involving direct contact with a healthcare worker. Contact tracing connected patient cases to interactions with healthcare workers.

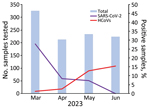

The SARS-CoV-2 positivity rate during the outbreak period (March–June) varied from 7.3% to 27.9% (Figure); no cases were reported in June. To provide background for the outbreak, we conducted surveillance testing for respiratory viruses collected 2 months before (January–February) and after (July–August) the outbreak; no HCoV was detected during those periods. In previous studies conducted at our hospital before the COVID-19 pandemic, we did not observe >5% monthly circulation of HCoVs during the study years under investigation (5). The HCoV-OC43 outbreak peak occurred after the disappearance of SARS-CoV-2 cases (Figure).

In this outbreak, hospitalized patients showed evolution of a severe form of infection caused by HCoV-OC43. Nirmatrelvir/ritonavir is a promising antiviral drug combination in preclinical studies that inhibits the proteolytic activity of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro, a cysteine protease found in the family Coronaviridae (6), and might be useful for treating HCoV-OC43 infections.

At the end of March 2023 in Brazil, the National Health Surveillance Agency (Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária) updated guidelines for mask use in healthcare settings. Since April 2023, the hospital committee has relaxed the requirement for universal mask use, making them obligatory only in areas designated for patient care (7). Relaxing mask use by healthcare workers who provide care to high-risk patients likely contributed to nosocomial acquisition of HCoV-OC43. Furthermore, healthcare workers who had respiratory infections other than SARS-CoV-2 infections were likely less vigilant in using personal protective equipment during patient care. In addition, an unconscious relaxation in maintaining precautions might have occurred, possibly because persons did not perceive themselves as potential transmitters.

In conclusion, we report the occurrence of HCoV-OC43 causing severe acute respiratory infection that might be underestimated because of a lack of better diagnostic approaches for viral respiratory infections, particularly in high-risk patients. Routine surveillance using a diagnostic panel of respiratory viruses can improve detection in both healthcare workers and patients and can help determine prevalence and prevent transmission of different viruses.

Dr. Chaves is an infectious and tropical diseases research scientist at the Evandro Chagas Institute/Secretariat of Health and Environment Surveillance at the Brazilian Ministry of Health, professor at the Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade Federal do Pará, Belém, Brazil, and a postdoctoral research scientist at the Federal University of São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil. Her primary research interests are epidemiologic and clinical studies of infectious and tropical diseases, emerging and reemerging diseases, public health¸ and travel medicine.

N.B., A.H.P., and T.S.S.C. conceived and designed the study and contributed to data analysis; A.H.P., D.B.F., and G.B. contributed to diagnostic, patient, and public health surveillance data analysis; and N.B., T.S.S.C., and G.B. wrote the first draft. All authors contributed and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgment

T.S.S.C was supported by the Evandro Chagas Institute at the Ministry of Health of Brazil and the School of Medicine at the Federal University of Pará.

References

- Chow EJ, Uyeki TM, Chu HY. The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on community respiratory virus activity. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2023;21:195–210.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Vabret A, Mourez T, Gouarin S, Petitjean J, Freymuth F. An outbreak of coronavirus OC43 respiratory infection in Normandy, France. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:985–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Kesheh MM, Hosseini P, Soltani S, Zandi M. An overview on the seven pathogenic human coronaviruses. Rev Med Virol. 2022;32:

e2282 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Dare RK, Fry AM, Chittaganpitch M, Sawanpanyalert P, Olsen SJ, Erdman DD. Human coronavirus infections in rural Thailand: a comprehensive study using real-time reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction assays. J Infect Dis. 2007;196:1321–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Cabeça TK, Granato C, Bellei N. Epidemiological and clinical features of human coronavirus infections among different subsets of patients. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2013;7:1040–7. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Owen DR, Allerton CMN, Anderson AS, Aschenbrenner L, Avery M, Berritt S, et al. An oral SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitor clinical candidate for the treatment of COVID-19. Science. 2021;374:1586–93. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- ANVISA. Technical Note GVIMS/GGTES/ANVISA No.04/2020. Guidelines for health services: prevention and control measures that must be adopted when providing care to suspected or confirmed cases of COVID-9 infection [in Portuguese] [cited 2024 Jan 3]. https://www.gov.br/anvisa/pt-br/centraisdeconteudo/publicacoes/servicosdesaude/notas-tecnicas/2020/nota-tecnica-gvims_ggtes_anvisa-04_2020-25-02-para-o-site.pdf

Figure

Table

Cite This ArticleOriginal Publication Date: January 30, 2024

Table of Contents – Volume 30, Number 3—March 2024

| EID Search Options |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Please use the form below to submit correspondence to the authors or contact them at the following address:

Tânia do Socorro Souza Chaves, Universidade Federal de São Paulo, Rua Pedro de Toledo 781, São Paulo CEP 04039-032, Brazil; Evandro Chagas Institute/Secretariat of Health and Environment Surveillance/Brazilian Ministry of Health, Rodovia BR-316 km 7 s/n, Ananindeua CEP 67030-000, Brazil; or Universidade Federal do Pará/Instituto de Ciências Médicas, Avenida Generalíssimo Deodoro número 1, Belém CEP 66050-060, Brazil

Top