Volume 31, Number 6—June 2025

Research

Force of Infection Model for Estimating Time to Dengue Virus Seropositivity among Expatriate Populations, Thailand

Figure

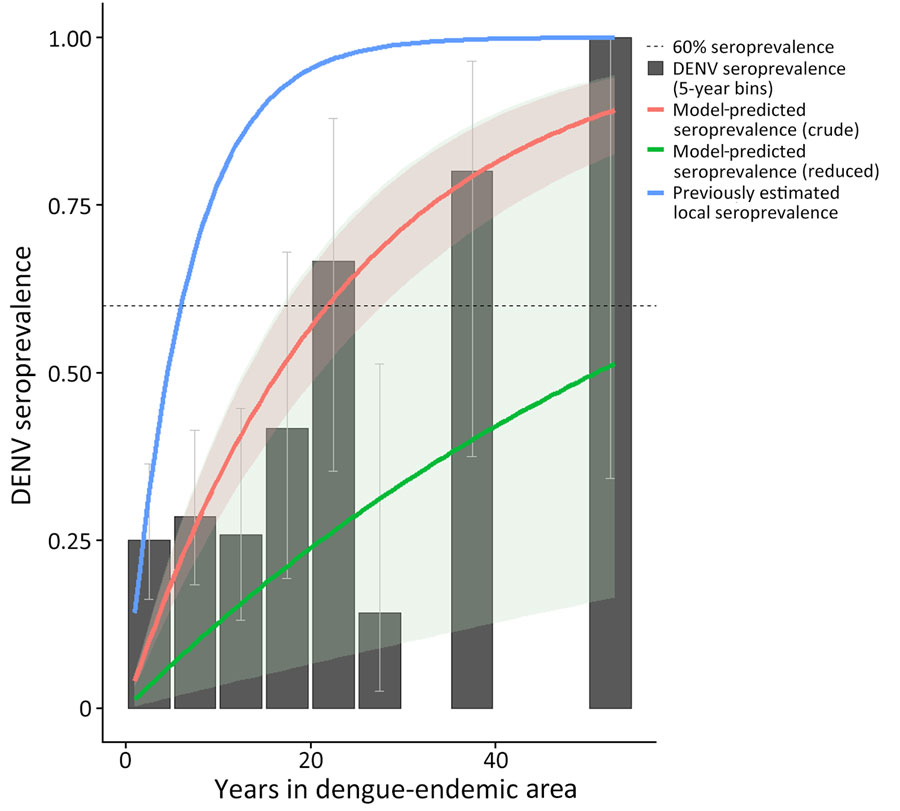

Figure. Crude force of infection by years in dengue-endemic area (DEA) in study of force of infection model for estimating time to DENV seropositivity among expatriate populations, Thailand. A serocatalytic model estimating dengue force of infection was fit using a binomial model with a cloglog link function with log(years in DEA) as an offset. Solid red line represents the crude model; solid green line represents the reduced model. The solid blue line represents approximate seroprevalence among locals of Thailand, as modeled by Hamins Puertolas et al. (25). Dotted line indicates 60% DENV seroprevalence. Black bars show the seroprevalence of DENV among all study participants in 5-year bins of years spent in a DEA. Uncertainty in measured seroprevalence was calculated using the Wilson confidence interval for proportions (30). DENV, dengue virus.

References

- Cattarino L, Rodriguez-Barraquer I, Imai N, Cummings DAT, Ferguson NM. Mapping global variation in dengue transmission intensity. Sci Transl Med. 2020;12:

eaax4144 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - World Health Organization. Dengue and severe dengue [2020 Apr 12]. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dengue-and-severe-dengue

- Halstead SB, Yamarat C. Recent epidemics of hemorrhagic fever in Thailand: observations related to pathogenesis of a “new” dengue disease. Am J Public Health Nations Health. 1965;55:1386–95. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Sabin AB. Research on dengue during World War II. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1952;1:30–50. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Dengue shock syndrome (DSS) 2010 case definition [cited 2024 Jan 29]. https://ndc.services.cdc.gov/case-definitions/dengue-shock-syndrome-2010

- Halstead SB, Rojanasuphot S, Sangkawibha N. Original antigenic sin in dengue. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1983;32:154–6. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Bhatt S, Gething PW, Brady OJ, Messina JP, Farlow AW, Moyes CL, et al. The global distribution and burden of dengue. Nature. 2013;496:504–7. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Naish S, Dale P, Mackenzie JS, McBride J, Mengersen K, Tong S. Climate change and dengue: a critical and systematic review of quantitative modelling approaches. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:167. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Rocklöv J, Tozan Y. Climate change and the rising infectiousness of dengue. Emerg Top Life Sci. 2019;3:133–42. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Gubler DJ. Dengue, urbanization and globalization: the unholy trinity of the 21st century. Trop Med Health. 2011;39(Suppl):3–11. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Menon S, Wilder-Smith A. New vaccines on the immediate horizon for travelers: chikungunya and dengue vaccines. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2023;25:211–24. DOIGoogle Scholar

- Thomas SJ. Is new dengue vaccine efficacy data a relief or cause for concern? NPJ Vaccines. 2023;8:55. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Kallás EG, Cintra MAT, Moreira JA, Patiño EG, Braga PE, Tenório JCV, et al. Live, attenuated, tetravalent butantan-dengue vaccine in children and adults. N Engl J Med. 2024;390:397–408. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Nogueira ML, Cintra MAT, Moreira JA, Patiño EG, Braga PE, Tenório JCV, et al.; Phase 3 Butantan-DV Working Group. Efficacy and safety of Butantan-DV in participants aged 2-59 years through an extended follow-up: results from a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3, multicentre trial in Brazil. Lancet Infect Dis. 2024;24:1234–44. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Angelin M, Sjölin J, Kahn F, Ljunghill Hedberg A, Rosdahl A, Skorup P, et al. Qdenga® - A promising dengue fever vaccine; can it be recommended to non-immune travelers? Travel Med Infect Dis. 2023;54:

102598 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Freedman DO. A new dengue vaccine (TAK-003) now WHO recommended in endemic areas; what about travellers? J Travel Med. 2023;30:

taad132 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - World Health Organization. WHO position paper on dengue vaccines–May 2024 [cited 2024 Sep 4]. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/376641/WER9918-eng-fre.pdf

- Duvignaud A, Stoney RJ, Angelo KM, Chen LH, Cattaneo P, Motta L, et al.; GeoSentinel Network. Epidemiology of travel-associated dengue from 2007 to 2022: A GeoSentinel analysis. J Travel Med. 2024;31:

taae089 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Kitro A, Ngamprasertchai T, Srithanaviboonchai K. Infectious diseases and predominant travel-related syndromes among long-term expatriates living in low-and middle- income countries: a scoping review. Trop Dis Travel Med Vaccines. 2022;8:11. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- World Population Review. Bangkok population 2023 [cited 2023 Dec 26]. https://worldpopulationreview.com/world-cities/bangkok-population

- Shepherd SM, Shoff WH. Vaccination for the expatriate and long-term traveler. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2014;13:775–800. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Reiter P, Lathrop S, Bunning M, Biggerstaff B, Singer D, Tiwari T, et al. Texas lifestyle limits transmission of dengue virus. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003;9:86–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Ribeiro Dos Santos G, Buddhari D, Iamsirithaworn S, Khampaen D, Ponlawat A, Fansiri T, et al. Individual, household, and community drivers of dengue virus infection risk in Kamphaeng Phet Province, Thailand. J Infect Dis. 2022;226:1348–56. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Anderson KB, Buddhari D, Srikiatkhachorn A, Gromowski GD, Iamsirithaworn S, Weg AL, et al. An innovative, prospective, hybrid cohort-cluster study design to characterize dengue virus transmission in multigenerational households in Kamphaeng Phet, Thailand. Am J Epidemiol. 2020;189:648–59. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Hamins-Puértolas M, Buddhari D, Salje H, Cummings DAT, Fernandez S, Farmer A, et al. Household immunity and individual risk of infection with dengue virus in a prospective, longitudinal cohort study. Nat Microbiol. 2024;9:274–83. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Rodríguez-Barraquer I, Buathong R, Iamsirithaworn S, Nisalak A, Lessler J, Jarman RG, et al. Revisiting Rayong: shifting seroprofiles of dengue in Thailand and their implications for transmission and control. Am J Epidemiol. 2014;179:353–60. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Kitro A, Imad HA, Pisutsan P, Matsee W, Sirikul W, Sapbamrer R, et al. Seroprevalence of dengue, Japanese encephalitis and Zika among long-term expatriates in Thailand. J Travel Med. 2024;31:

taae022 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Russell PK, Nisalak A. Dengue virus identification by the plaque reduction neutralization test. J Immunol. 1967;99:291–6. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Rue H, Martino S, Chopin N. Approximate bayesian inference for latent gaussian models by using integrated nested laplace approximations. J R Stat Soc Series B Stat Methodol. 2009;71:319–92. DOIGoogle Scholar

- Wilson EB. Probable inference, the law of succession, and statistical inference. J Am Stat Assoc. 1927;22:209–12. DOIGoogle Scholar

- McElreath R. Statistical rethinking: a Bayesian course with examples in R and Stan. New York: CRC Press Taylor & Francis; 2016.

- Nealon J, Bouckenooghe A, Cortes M, Coudeville L, Frago C, Macina D, et al. Dengue endemicity, force of infection, and variation in transmission intensity in 13 endemic countries. J Infect Dis. 2022;225:75–83. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Hamins-Puértolas M, Buddhari D, Salje H, Cummings DAT, Fernandez S, Farmer A, et al. Household immunity and individual risk of infection with dengue virus in a prospective, longitudinal cohort study. Nat Microbiol. 2024;9:274–83. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Patel RV, Shaeer KM, Patel P, Garmaza A, Wiangkham K, Franks RB, et al. EPA-registered repellents for mosquitoes transmitting emerging viral disease. Pharmacotherapy. 2016;36:1272–80. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Lupi E, Hatz C, Schlagenhauf P. The efficacy of repellents against Aedes, Anopheles, Culex and Ixodes spp. - a literature review. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2013;11:374–411. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Kitro A, Sirikul W, Piankusol C, Rirermsoonthorn P, Seesen M, Wangsan K, et al. Acceptance, attitude, and factors affecting the intention to accept COVID-19 vaccine among Thai people and expatriates living in Thailand. Vaccine. 2021;39:7554–61. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- NSO. Population and Housing Census [cited 2025 Jan 15]. https://www.nso.go.th/nsoweb/main/summano/aE?year=957&type=3309#data__report

- Jaisuekun K, Sunanta S. German migrants in Pattaya, Thailand: gendered mobilities and the blurring boundaries between sex tourism, marriage migration, and lifestyle migration. In: Mora C, Piper N, editors. The Palgrave Handbook of Gender and Migration. Cham (Switzerland): Springer International Publishing; 2021. p. 137–149.

- Kerdpanich P, Kongkiatngam S, Buddhari D, Simasathien S, Klungthong C, Rodpradit P, et al. Comparative analyses of historical trends in confirmed dengue illnesses detected at public hospitals in Bangkok and northern Thailand, 2002–2018. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2020;104:1058–66. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- World Health Organization. Combating dengue outbreak and addressing overlapping challenges with COVID-19 [cited 2024 Jan 5]. https://www.who.int/thailand/news/detail/30-06-2023-combating-dengue-outbreak-and-addressing-overlapping-challenges-with-covid-19

- Ooi EE, Kalimuddin S. Insights into dengue immunity from vaccine trials. Sci Transl Med. 2023;15:

eadh3067 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Lim JK, Carabali M, Edwards T, Barro A, Lee JS, Dahourou D, et al. Estimating the force of infection for dengue virus using repeated serosurveys, Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso. Emerg Infect Dis. 2021;27:130–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Biggs JR, Sy AK, Sherratt K, Brady OJ, Kucharski AJ, Funk S, et al. Estimating the annual dengue force of infection from the age of reporting primary infections across urban centres in endemic countries. BMC Med. 2021;19:217. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

1These last authors contributed equally to this article.