Volume 4, Number 2—June 1998

Synopsis

Multiple-Drug Resistant Enterococci: The Nature of the Problem and an Agenda for the Future

Figure 4

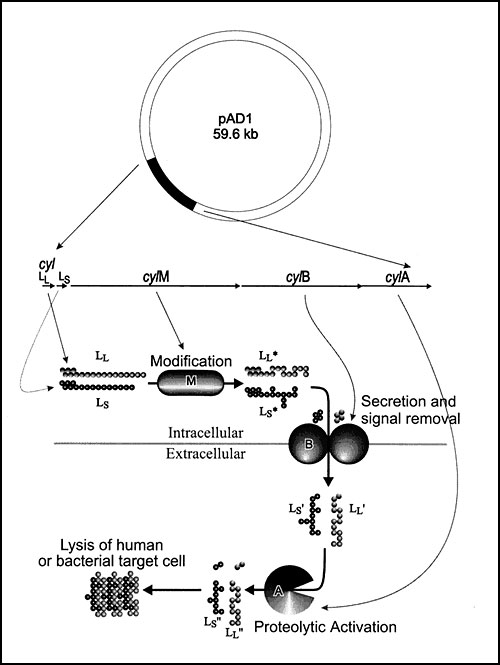

Figure 4. Cytolysin is expressed and processed through a complex maturation pathway (64). The cytolysin precursors, CylLL and CylLS, are ribosomally synthesized. The putative modification protein, CylM, is required for the expression of CylLL and CylLS in an activatable form, and the secreted forms, CylLL and CylLS were recently shown to possess the amino acid lanthionine as the result of posttranslational modification (64). CylLL and CylLS both are secreted by CylB (65), which is accompanied by an initial proteolytic trimming event (64) converting each to CylLL' and CylLS', respectively. Once secreted, CylLL' and CylLS' are both functionally inactive until six amino acids are removed from each amino terminus. This final step in maturation is catalyzed by CylA (64), a subtilisin-type serine protease. Since this final catalytic event is essential, occurs extracellularly, and is catalyzed by a class of enzyme for which a substantial body of structural information exists, it represents an ideal therapeutic target. As shown in Figure 3, inhibition of cytolysin by mutation (or potentially by therapeutic intervention) results in a reduction by several orders of magnitude in the number of circulating organisms.

References

- Kaye D. Enterococci: biologic and epidemiologic characteristics and in vitro susceptibility. Arch Intern Med. 1982;142:2006–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Emori TG, Gaynes RP. An overview of nosocomial infections, including the role of the microbiology laboratory. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1993;6:428–42.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Jarvis WR, Gaynes RP, Horan TC, Emori TG, Stroud LA, Archibald LK, Semiannual report: aggregated data from the National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance (NNIS) system. CDC, 1996:1-27.

- Cohen ML. Epidemiology of drug resistance: implications for a post-antimicrobial era. Science. 1992;257:1050–5. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Jett BD, Huycke MM, Gilmore MS. Virulence of enterococci. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1994;7:462–78.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Rice EW, Messer JW, Johnson CH, Reasoner DJ. Occurrence of high-level aminoglycoside resistance in environmental isolates of enterococci. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:374–6.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Devriese LA, Pot B, Collins MD. Phenotypic identification of the genus Enterococcus and differentiation of phylogenetically distinct enterococcal species and species groups. J Appl Bacteriol. 1993;75:399–408.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Willett HP. Energy metabolism. In: Joklik WK, Willett HP, Amos DB, Wilfert CM, editors. Zinsser microbiology. 20th ed. East Norwalk (CT): Appleton & Lange; 1992. p. 53-75.

- Ritchey TW, Seeley HW. Cytochromes in Streptococcus faecalis var. zymogenes grown in a haematin-containing medium. J Gen Microbiol. 1974;85:220–8.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Pritchard GG, Wimpenny JWT. Cytochrome formation, oxygen-induced proton extrusion and respiratory activity in Streptococcus faecalis var. zymogenes grown in the presence of haematin. J Gen Microbiol. 1978;104:15–22.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Ritchey TW, Seeley HW Jr. Distribution of cytochrome-like respiration in streptococci. J Gen Microbiol. 1976;93:195–203.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Bryan-Jones DG, Whittenbury R. Haematin-dependent oxidative phosphorylation in Streptococcus faecalis. J Gen Microbiol. 1969;58:247–60.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Williamson R. Le Bougu,nec C, Gutmann L, Horaud T. One or two low affinity penicillin-binding proteins may be responsible for the range of susceptibility of Enterococcus faecium to benzylpenicillin. J Gen Microbiol. 1985;131:1933–40.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Bush LM, Calmon J, Cherney CL, Wendeler M, Pitsakis P, Poupard J, High-level penicillin resistance among isolates of enterococci: implications for treatment of enterococcal infections. Ann Intern Med. 1989;110:515–20.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Sapico FL, Canawati HN, Ginunas VJ, Gilmore DS, Montgomerie JZ, Tuddenham WJ, Enterococci highly resistant to penicillin and ampicillin: an emerging clinical problem? J Clin Microbiol. 1989;27:2091–5.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Horodniceanu T, Bougueleret L, El-Solh N, Bieth G, Delbos F. High-level, plasmid-borne resistance to gentamicin in Streptococcus faecalis subsp zymogenes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1979;16:686–9.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Zervos MJ, Kauffman CA, Therasse PM, Bergman AG, Mikesell TS, Schaberg DR. Nosocomial infection by gentamicin-resistant Streptococcus faecalis: an epidemiologic study. Ann Intern Med. 1987;106:687–91.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Murray BE, Singh KV, Markowitz SM, Lopardo HA, Patterson JE, Zervos MJ, Evidence for clonal spread of a single strain of ß-lactamase-producing Enterococcus (Streptococcus) faecalis to six hospitals in five states. J Infect Dis. 1991;163:780–5.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Uttley AHC, Collins CH, Naidoo J, George RC. Vancomycin-resistant enterococci. Lancet. 1988;1:57–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Leclercq R, Derlot E, Duval J, Courvalin P. Plasmid-mediated resistance to vancomycin and teicoplanin in Enterococcus faecium. N Engl J Med. 1988;319:157–61.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Sahm DF, Kissinger J, Gilmore MS, Murray PR, Mulder R, Solliday J, In vitro susceptibility studies of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecalis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1989;33:1588–91.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Arthur M, Courvalin P. Genetics and mechanisms of glycopeptide resistance in enterococci. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:1563–71.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Clark NC, Cooksey RC, Hill BC, Swenson JM, Tenover FC. Characterization of glycopeptide-resistant enterococci from U.S. hospitals. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:2311–7.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Klare I, Heier H, Claus H, Reissbrodt R, Van Witte W. A-mediated high-level glycopeptide resistance in Enterococcus faecium from animal husbandry. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1995;125:165–72. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Noble WC, Virani Z, Cree RGA. Co-transfer of vancomycin and other resistance genes from Enterococcus faecalis NCTC 12201 to Staphylococcus aureus. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1992;93:195–8. DOIGoogle Scholar

- Hiramatsu K, Hanaki H, Ino T, Yabuta K, Oguri T, Tenover FC. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clinical strain with reduced vancomycin susceptibility. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1997;40:135–46. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Haley RW, Culver DH, White JW, Meade WM, Emori TG, Munn VP, The efficacy of infection surveillance and control programs in preventing nosocomial infections in US hospitals. Am J Epidemiol. 1985;121:182–205.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Harris SL. Definitions and demographic characteristics. In: Kaye D, editor. Infective endocarditis. New York: Raven Press, Ltd.; 1992. p. 1-18.

- Hughes JM, Culver DH. W, Morgan WM, Munn VP, Mosser JL, Emori TG. Nosocomial infection surveillance, 1980-1982. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 1983;32:1SS-16SS.

- Edmond MB, Ober JF, Dawson JD, Weinbaum DL, Wenzel RP. Vancomycin-resistant enterococcal bacteremia: natural history and attributable mortality. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;23:1234–9.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Rhinehart E, Smith NE, Wennersten C, Gorss E, Freeman J, Eliopoulos GM, Rapid dissemination of ß-lactamase-producing, aminoglycoside-resistant Enterococcus faecalis among patients and staff on an infant-toddler surgical ward. N Engl J Med. 1990;26:1814–8.

- Chow JW, Kuritza A, Shlaes DM, Green M, Sahm DF, Zervos MJ. Clonal spread of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium between patients in three hospitals in two states. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:1609–11.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Montecalvo MA, Horowitz H, Gedris C, Carbonaro C, Tenover FC, Issah A, Outbreak of vancomycin-, ampicillin-, and aminoglycoside-resistant Enterococcus faecium bacteremia in an adult oncology unit. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:1363–7.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Livornese LL, Dias S, Samel C, Romanowski B, Taylor S, May P, Hospital-acquired infection with vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium transmitted by electronic thermometers. Ann Intern Med. 1992;117:112–6.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Handwerger S, Raucher B, Altarac D, Monka J, Marchione S, Singh KV, Nosocomial outbreak due to Enterococcus faecium highly resistant to vancomycin, penicillin, and gentamicin. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;16:750–5.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommendations for preventing the spread of vancomycin resistance: recommendations of the Hospital Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee (HICPAC). MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1995;44(No. RR-12):1–13.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Morris JG Jr, Shay DK, Hebden JN, McCarter RJ Jr, Perdue BE, Jarvis W, Enterococci resistant to multiple antimicrobial agents, including vancomycin. Ann Intern Med. 1995;123:250–9.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Edmond MB, Ober JF, Weinbaum DL, Pfaller MA, Hwang T, Sanford MD, Vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium bacteremia: risk factors for infection. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;20:1126–33.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Goldmann D, Larson E. Hand-washing and nosocomial infections. N Engl J Med. 1992;327:120–2.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Noskin GA, Stosor V, Cooper I, Peterson LR. Recovery of vancomycin-resistant enterococci on fingertips and environmental surfaces. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1995;16:577–81. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Vollaard EJ, Clasener HAL. Colonization resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:409–14.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Quale J, Landman D, Saurina G, Atwood E, DiTore V, Patel K. Manipulation of a hospital antimicrobial formulary to control an outbreak of vancomycin-resistant enterococci. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;23:1020–5.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Caron F, Pestel M, Kitzis M-D, Lemeland JF, Humbert G, Gutmann L. Comparison of different ß-lactam-glycopeptide-gentamicin combinations for an experimental endocarditis caused by a highly ß-lactam-resistant and highly glycopeptide-resistant isolate of Enterococcus faecium. J Infect Dis. 1995;171:106–12.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Norris AH, Reilly JP, Edelstein PH, Brennan PJ, Schuster MG. Chloramphenicol for the treatment of vancomycin-resistant enterococcal infections. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;20:1137–44.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Cohen MA, Yoder SL, Huband MD, Roland GE, Courtney CL. In vitro and in vivo activities of clinafloxacin, CI-990 (PD 131112), and PD 138312 versus enterococci. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:2123–7.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Aumercier M, Bouhallab S, Capmau M-L, LeGoffic F. RP 59500: A proposed mechanism for its bactericidal activity. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1992;30(Suppl A):9–14.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Collins LA, Malanoski GJ, Eliopoulos GM, Wennersten CB, Ferraro MJ, Moellering RC Jr. In vitro activity of RP59500, an injectable streptogramin antibiotic, against vancomycin-resistant gram-positive organisms. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:598–601.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Chow JW, Davidson A, Sanford E III, Zervos MJ. Superinfection with Enterococcus faecalis during quinupristin/dalfopristin therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24:91–2.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Chow JW, Donahedian SM, Zervos MJ. Emergence of increased resistance to quinupristin/dalfopristin during therapy for Enterococcus faecium bacteremia. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24:90–1.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Eliopoulos GM, Wennersten CB, Cole G, Moellering RC. In vitro activities of two glycylcyclines against gram-positive bacteria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:534–41.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Jones RN, Johnson DM, Erwin ME. In vitro antimicrobial activities and spectra of U-100592 and U-100766, two novel fluorinated oxazolidinones. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:720–6.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Hillyard DR. The molecular approach to microbial diagnosis. Am J Clin Pathol. 1994;101:S18–21.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Strohl WR. Biotechnology of Antibiotics. 2nd ed: Drugs and the Pharmaceutical Sciences 82, 1997.

- Jett BD, Jensen HG, Nordquist RE, Gilmore MS. Contribution of the pAD1-encoded cytolysin to the severity of experimental Enterococcus faecalis endophthalmitis. Infect Immun. 1992;60:2445–52.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Ike Y, Hashimoto H, Clewell DB. High incidence of hemolysin production by Enterococcus (Streptococcus) faecalis strains associated with human parenteral infections. J Clin Microbiol. 1987;25:1524–8.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Huycke MM, Spiegel CA, Gilmore MS. Bacteremia caused by hemolytic, high-level gentamicin-resistant Enterococcus faecalis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1991;35:1626–34.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Jett BD, Jensen HG, Atkuri R, Gilmore MS. Evaluation of therapeutic measures for treating endophthalmitis cause by isogenic toxin producing and toxin non-producing Enterococcus faecalis strains. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1995;36:9–15.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Ike Y, Hashimoto H, Clewell DB. Hemolysin of Streptococcus faecalis subspecies zymogenes contributes to virulence in mice. Infect Immun. 1984;45:528–30.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Chow JW, Thal LA, Perri MB, Vazquez JA, Donabedian SM, Clewell DB, Plasmid-associated hemolysin and aggregation substance production contributes to virulence in experimental enterococcal endocarditis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:2474–7.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Ike Y, Clewell DB. Genetic analysis of pAD1 pheromone response in Streptococcus faecalis using transposon Tn917 as an insertional mutagen. J Bacteriol. 1984;158:777–83.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Ike Y, Clewell DB, Segarra RA, Gilmore MS. Genetic analysis of the pAD1 hemolysin/bacteriocin determinant in Enterococcus faecalis: Tn917 insertional mutagenesis and cloning. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:155–63.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Huycke MM, Gilmore MS. Frequency of aggregation substance and cytolysin genes among enterococcal endocarditis isolates. Plasmid. 1995;34:152–6. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Todd EW. A comparative serological study of streptolysins derived from human and from animal infections, with notes on pneumococcal haemolysin, tetanolysin and staphylococcus toxin. J Pathol Bacteriol. 1934;39:299–321. DOIGoogle Scholar

- Booth MC, Bogie CP, Sahl H-G, Siezen RJ, Hatter KL, Gilmore MS. Structural analysis and proteolytic activation of Enterococcus faecalis cytolysin, a novel lantibiotic. Mol Microbiol. 1996;21:1175–84. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Gilmore MS, Segarra RA, Booth MC. An hlyB-type function is required for expression of the Enterococcus faecalis hemolysin/bacteriocin. Infect Immun. 1990;58:3914–23.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Katz L, Chu DT, Reich K. Bacterial genomics and the search for novel antibiotics. In: Plattner JJ, editor. Annual Reports in Medicinal Chemistry. Vol. 32. New York: Academic Press, Inc., 1997. p. 121-30.

- Shankar V, Gilmore MS. Structure and expression of a novel surface protein of Enterococcus faecalis. In: Abstracts of the 97th General Meeting of the American Society for Microbioloty; 4-8 May 1997;Miami Beach, Florida. Washington: The Society; 1997.

- Hancock LE, Gilmore MS. The contribution of a cell wall associated carbohydrate to the in vivo survival of Enterococcus faecalis in a murine model of infection. In: Abstracts of the 97th General Meeting of the American Society for Microbioloty. 4-8 May 1997;Miami Beach, Florida. Washington: The Society; 1997.

- Arduino RC, Murray BE, Rakita RM. Roles of antibodies and complement in phagocytic killing of enterococci. Infect Immun. 1994;62:987–93.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Arduino RC, Palaz-Jacques K, Murray BE, Rakita RM. Resistance of Enterococcus faecium to neutrophil-mediated phagocytosis. Infect Immun. 1994;62:5587–94.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Huycke MM, Joyce W, Wack MF. Augmented production of extracellular superoxide production by blood isolates of Enterococcus faecalis. J Infect Dis. 1996;173:743–6.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Swartz MN. Hospital-acquired infections: diseases with increasingly limited therapies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:2420–7. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar