Volume 5, Number 2—April 1999

Dispatch

Neospora caninum Infection and Repeated Abortions in Humans

Abstract

To determine whether Neospora caninum, a parasite known to cause repeated abortions and stillbirths in cattle, also causes repeated abortions in humans, we retrospectively examined serum samples of 76 women with a history of abortions for evidence of N. caninum infection. No antibodies to the parasite were detected by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, immunofluorescence assay, or Western blot.

Neospora caninum, an intracellular protozoan parasite closely related to Toxoplasma gondii (1,2), was first described in dogs in Norway in 1984 and later in a wide range of other mammals including cattle, goats, horses, and sheep. The life cycle of N. caninum is only partially known, but the dog has recently been established as its definitive host (3). The pathogen's only known natural route of transmission (which can occur during sequential pregnancies in cattle) is transplacental (4).

N. caninum is now recognized as the most common cause of repeated abortions and stillbirths in cattle, and infected herds have been reported in most parts of the world, including Scandinavia (4-6). Infected, live-borne offspring may have neurologic symptoms including progressive paralysis. When experimentally transferred to pregnant nonhuman primates, N. caninum has caused fetal infection. The fetal lesions closely resembled those in congenital toxoplasmosis (7). N. caninum organisms are morphologically very similar to T. gondii, the pathogen responsible for toxoplasmosis; however, the two species have distinct antigenic characteristics and can be distinguished by serologic and immunohistochemical methods (4).

No case of N. caninum infection has been described in humans. However, because of the organism's close phylogenetic relationship to T. gondii and its wide range of potential hosts, the possibility of human N. caninum infection cannot be excluded. We investigated serologically the possible presence of N. caninum infection in Danish women who had repeated abortions of unknown cause.

The study included 76 women (mean age 30.8 years, range 19 to 41 years) who had had repeated abortions or intrauterine death of the fetus. Blood samples were obtained at the time of abortion or within 3 months of fetal death. The study participants had been referred to the Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics, Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen, Denmark, between 1 September 1991 and 31 October 1992 as part of a larger study of pregnant women with repeated primary or secondary abortions or repeated intrauterine fetal deaths. Serum specimens were tested for antibodies to N. caninum and T. gondii as described below.

The absorbence values for the human serum samples were 0.10 to 1.24 absorbence units, whereas the mean value for the presumed N. caninum-negative human control serum was 0.26 (0.13 to 0.56). The mean absorbence values for the high-positive and low-positive control pig sera were 1.73 (1.54 to 1.93) and 0.87 (0.85 to 1.07), respectively. As no true N. caninum-negative or -positive human sera were available, serum specimens with absorbencies 0.50 (n = 12) were selected for further investigation (Table).

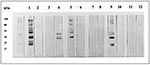

None of the 12 specimens showed specific fluorescence in the indirect fluorescence antibody test (IFAT) at dilution 1:640 with N. caninum tachyzoites that had been cultivated in vitro (6). (Sera had been diluted in twofold serial dilutions from 1:20 in phosphate-buffered saline.) Of the 12, only 3 had T. gondii antibodies. The reactivities in the N. caninum enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) were not associated with the presence of T. gondii antibodies (Table). Only 1 of the 12 human serum specimens tested showed reactivity against the N. caninum antigen by Western blot analysis. This specimen, number 279, recognized an antigen with apparent molecular weight of 60 kDa (Figure, lane 11 and 12). This antigen was not recognized by the N. caninum-positive pig sera, and serum 279 did not recognize any of the low-molecular weight antigens recognized by the N. caninum-positive pig sera. Three serum specimens reacted with the T. gondii antigen; all were T. gondii-positive in the dye test.

Because of the biologic similarities between N. caninum and the human pathogen T. gondii, it has been speculated that N. caninum could be transmissible to humans. Since repeated abortions and stillbirths are common manifestations of neosporosis in cattle (4), women with a history of repeated abortions seemed an obvious category to investigate for human N. caninum infection. However, in this study of serum samples from women with repeated abortions, no evidence of N. caninum infection was detected.

The assays we used were based on methods used for T. gondii analyses; we used the same conjugates and serum dilutions found optimal in these analyses. The N. caninum immunostimulating complex antigen has a high specificity (14) and has been used for serologic investigations in different animal species (8,9,15). It was therefore anticipated that it would be applicable in a human system as well. However, because we could not define a proper cut-off for the assay, we further investigated the serum samples with the highest ELISA absorbence values by IFAT, regarded as the reference test for N. caninum antibodies in different species (4), and Western blot. None of the human sera investigated showed any reactivity in IFAT. Only one of the specimens reacted with the N. caninum antigen in the Western blot. However, because it only reacted with a band not recognized by sera from the infected pigs, the reaction was considered unspecific, and cross-reactivity between T. gondii and N. caninum was not found.

That we found no evidence of N. caninum infection in women who had repeated spontaneous abortions does not rule out the possibility that the infection might occur in humans. The predominant effects of neosporosis in dogs are primarily progressive neurologic signs including paralysis. It might, therefore, be worthwhile to examine human patients with clinical symptoms other than abortions, e.g., neurologic disorders of unknown etiology. Furthermore, the possible presence of N. caninum in patients with weakened immune systems should be considered. Researchers might continue the search for N. caninum by using serologic tests, as we did, or, alternatively, by using material collected at biopsy or autopsy for polymerase chain reaction or immunohistochemical analysis.

Dr. Petersen is a specialist in infectious diseases and tropical medicine at the Laboratory of Parasitology, Statens Serum Institut, Denmark's national reference center for diagnosis and research of human parasitic infections. His areas of expertise include immunology and epidemiology, primarily applied to malaria and congenital toxoplasmosis.

Acknowledgment

We thank Lisbeth Petersen, Lis Wassmann, and Ann Lene Andresen for skillful technical assistance.

References

- Dubey JP, Carpenter JL, Speer CA, Topper MJ, Uggla A. Newly recognized fatal protozoan disease of dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1988;192:1269–85.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Holmdahl OJM, Mattsson JG, Uggla A, Johansson K-E. The phylogeny of Neospora caninum and Toxoplasma gondii based on ribosomal RNA sequences. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1994;119:187–92.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- McAllister MM, Dubey JP, Lindsay DS, Jolley WR, Wills RA, McGuire AM. Dogs are definitive hosts of Neospora caninum. Int J Parasitol. 1998;28:1473–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Dubey JP, Lindsay DS. A review of Neospora caninum and neosporosis. Vet Parasitol. 1996;67:1–59. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Holmdahl OJM, Björkman C, Uggla A. A case of Neospora associated bovine abortion in Sweden. Acta Vet Scand. 1995;36:279–81.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Agerholm JS, Willadsen CM, Nielsen TK, Giese SB, Holm E, Jensen L, Diagnostic studies of abortion in Danish dairy herds. J Vet Med. 1997;A44:551–8.

- Barr BC, Conrad PA, Sverlow KW, Tarantal AF, Hendrickx AG. Experimental fetal and transplacental Neospora infection in the nonhuman primate. Lab Invest. 1994;71:236–42.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Björkman C, Lundén A, Holmdahl J, Barber J, Tress AJ, Uggla A. Neospora caninum in dogs: detection of antibodies by ELISA using an iscom antigen. Parasite Immunol. 1994;16:643–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Björkman C, Holmdahl OJM, Uggla A. An indirect enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for demonstration of antibodies to Neospora caninum in serum and milk of cattle. Vet Parasitol. 1997;68:251–6. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Jensen L, Jensen TK, Lind P, Henriksen SA, Uggla A, Bille-Hansen V. Experimental porcine neosporosis. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand. 1998;106:475–82.

- Sabin AB, Feldman HA. Dyes as microchemical indicators of a new immunity phenomenon affecting a protozoon parasite (Toxoplasma). Science. 1948;108:660–3. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Sharma SD, Mullenax J, Araujo FG, Erlich HA, Remington JS. Western blot analysis of the antigens of Toxoplasma gondii recognized by human IgM and IgG antibodies. J Immunol. 1983;131:977–83.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Dubey JP, Hattel AL, Lindsay DS, Topper MJ. Neonatal Neospora caninum infection in dogs: isolation of the causative agent and experimental transmission. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1988;193:1259–63.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Björkman C, Lundén A. Application of iscom antigen preparations in ELISAs for diagnosis of Neospora and Toxoplasma infections. Int J Parasitol. 1998;28:187–93. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Huong LTT, Ljungström BL, Uggla A, Björkman C. Prevalence of antibodies to Neospora caninum and Toxoplasma gondii in cattle and water buffaloes in southern Vietnam. Vet Parasitol. 1998;75:53–7. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

Figure

Table

Cite This ArticleTable of Contents – Volume 5, Number 2—April 1999

| EID Search Options |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Please use the form below to submit correspondence to the authors or contact them at the following address:

Eskild Petersen, Laboratory of Parasitology, Statens Serum Institut, DK-2300 Copenhagen S. Denmark; fax:45-3268-3033

Top