Volume 7, Number 1—February 2001

Research

Emerging Chagas Disease: Trophic Network and Cycle of Transmission of Trypanosoma cruzi from Palm Trees in the Amazon

Figure 6

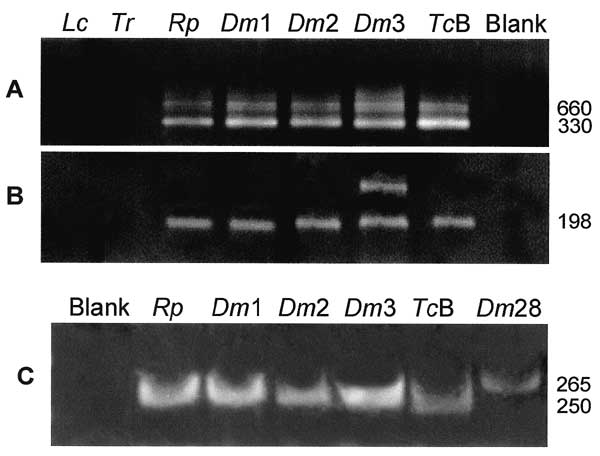

Figure 6. . Genotypic characterization of wild-type flagellates by PCR amplification with rDNA and mini-exon specific primers derived from Trypanosoma cruzi. A, template DNAs amplified with mini-exon intergenic spacer primers (38): Blank, negative control; Tcb, archetypic type II T. cruzi Berenice; Rp1, Dm1, Dm2 and Dm3, flagellates isolated from Rhodnius pictipes and from Didelphis marsupialis; Dm28, standard type I, sylvatic T. cruzi isolate. B, same template DNAs amplified with rDNA primers (39-41). Tcb yielded typical 300-bp band of type II lineage, whereas Rp1, Dm1, Dm2, and Dm3 and Dm28 yielded a 350-bp band of type I T. cruzi lineage, with mini-exon spacer primers. In addition, Tcb yielded typical a 125-bp band of type II, whereas the sylvatic T. cruzi isolates yielded a 110-bp band of type I, with rDNA primers. These findings confirm sylvatic Rp1, Dm1, Dm2, and Dm3 as T. cruzi.

References

- Dinerstein E, Olson DM, Graham DJ, Webster AL, Primm SA, Bookbinder MP, A conservation assessment of the terrestrial ecoregions of Latin America and the Caribbean. Ed. Washington: The World Wildlife Fund/The World Bank; 1995.

- La Foret en Jeu. L' Extractivisme en Amazonie Centrale. In: Emperaire L, editor. L' Orston: Institut Français de Recherche Scientifique pour le Développement en Coopéracion; Paris: Unesco; 1996. p. 116-59.

- Pindorama. São Paulo: Mercedes-Benz do Brazil; 1993.

- Kahn F, Corradini L. Palmeiras da Amazonia. Ed. Cendotec. Brasilia: Centro Franco Brasileiro de Documentação Científica; 1994. Contato, special volume. p. 11-6.

- Mapeamento e levantamento do potencial das ocorrências de babaçuais. Brasília: Núcleo de Comunicação Social da Secretaria de Tecnologia Industrial, Ministério da Indústria e do Comércio; 1982. p. 11-62.

- Moomen H. Emerging infectious diseases--Brazil. Emerg Infect Dis. 1998;4:351–4. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Brasil RP, Silva AR, Arbarelli A, Vale JF. Distribuição e infecção de triatomineos por Trypanosoma tipo cruzi na Ilha de São Luis, Maranhão. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 1985;18:257–60.

- Miles MA. Souza de AA, Póvoa M. Chagas diseases in the Amazon Basin. III. Ecotopes of ten triatomine bug species (Hemiptera: Reduvidae) from the vicinity of Belém, Pará State, Brazil. J Med Entomol. 1981;18:266–78.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Miles MA, Arias JR, Souza AA. Chagas disease in the Amazon Basin. V. Periurban palms as habitats of Rhodnius robustus and Rhodnius pictipes triatominae vectors of Chagas disease. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1983;78:391–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Lainson R, Shaw JJ, Fraiha H, Miles MA, Draper CC. Chagas disease in the Amazon Basin: Trypanosoma cruzi infections in sylvatic mammals, triatomine bugs and man in the State of Pará, north Brazil. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1979;73:193–204. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Recommendations from a satellite meeting. International Symposium to commemorate the 90th anniversary of the discovery of Chagas disease. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1999;94:429–32. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- D'Alessandro A, Barreto P, Saravia N, Barreto M. Epidemiology of Trypanosoma cruzi in the oriental plains of Colombia. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1984;33:1084–95.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Coura JR, Barret TV, Naranjo CM. Ataque de populações humanas por triatomineos silvestres no Amazonas: uma nova forma de transmissão da infecção Chagásica? Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 1994;27:251–3.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Valente VC, Valente SA, Noireau F, Carrasco HJ, Miles MA. Chagas disease in the Amazon Basin: association of Panstrongylus geniculatus (Hemiptera: Reduviidae) with domestic pigs. J Med Entomol. 1998;35:99–103.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Amunárriz MU, Chico ME, Guderian RH. Chagas disease in Ecuador: a sylvatic focus in the Amazon Region. J Trop Med Hyg. 1991;94:145–9.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Whitlaw JT, Chaniotis BN. Palm trees and Chagas' in Panama. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1978;27:873–81.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Almeida FB. Triatomíneos da Amazonia. Encontro de três espécies naturalmente infectadas por trypanosoma semelhante ao cruzi no Estado do Amazonas (Hemiptera, Reduviidae). Acta Amáz (Manaus). 1971;1:71–5.

- Coura JR. Doença de Chagas como endemia na amazonia brasileira: risco ou hipótese? Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 1990;23:67–70.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Fraiha Neto H, Valente SA, Valente VC, Pinto AYN. Doença de Chagas endemica na Amazonia. Rev Acad Med Pará, Belém. 1995;6:1–132.

- Chagas C. Infection naturelle des singes du Pará (Crysotrix sciureus) par Trypanosoma cruzi. C R Soc Biol (Paris). 1924;9:873–6.

- Raccurt CP. Trypanosoma cruzi in French Guinea: review of accumulated data since 1940. Med Trop. 1996;56:79–87.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Shaw JJ, Lainson R, Fraiha H. Considerações sobre a epidemiologia dos primeiros casos autóctones de doença de Chagas registrados em Belém, Pará, Brasil. Rev Bras Saúde Pública, São Paulo. 1969;3:153–7.

- Ferraroni JJ, Melo JAN, Camargo ME. Molestia de Chagas na Amazônia. Ocorrência de seis casos suspeitos, autóctones, sorologicamente positivos. Acta Amazon. 1977;3:438–9.

- Silva AR, Mendes JR, Mendonca ML, Cutrin RN, Brazil RP. Primeiros casos agudos autoctones da doença de Chagas no Maranhão e inquérito soro-epidemiologico da população. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 1985;18:269–70.

- Rodrigues CI, Souza AA, Terceros R, Valente S. Doença de Chagas na Amazonia: I Registro de oito casos autóctones em Macapa. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 1988;21:193–7.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Acosta HMS, Ferreira CS, Carvalho ME. Human infection with Trypanosoma cruzi in Nasca, Peru: a seroepidemiologic survey. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 1997;39:107–12. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Chico MH, Sandoval C, Guevara AE, Calvopiña MH, Cooper PJ, Reed SG, Chagas disease in Ecuador: evidence for disease transmission in an indigenous population in the Amazon Region. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1997;92:317–20. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Corredor-Arjona A, Moreno CA, Agudelo CA, Bueno M, López MC, Cáceres E, Prevalence of Trypanosoma cruzi and Leishmania chagasi infection and risk factors in a Colombian indigenous population. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 1999;41:229–4. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Spellerberg IF, Hardes S. Biological conservation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992.

- Williams-Blangero S, VandeBerg J, Blangero J, Teixeira ARL. Genetic epidemiology of seropositivity for Trypanosoma cruzi infection in rural Goias, Brazil. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1997;57:538–43.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Pedreira de Freitas JL, Siqueira AF, Ferreira OA. Investigações epidemiológicas sobre triatomíneos de hábitos domésticos e silvestres com auxílio da reação de precipitina. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 1960;2:90–9.

- Siqueira AF. Estudos sobre a reação da precipitina aplicada à identificação de sangue por triatomineos. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 1960;2:41–53.

- Teixeira ARL. The Stercorarian trypanosomes. In: Immune responses in parasitic infections: immunology, immunopathology and immunoprophylaxis. EJL Soulsby, editor. Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press, 1987. p. 125-45.

- Teixeira ARL, Teixeira G, Macedo V, Prata A. Acquired cell-mediated immunodepression in acute Chagas disease. J Clin Invest. 1978;62:1132–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Sturm NR, Degrave W, Morel CM, Simpson L. Sensitive detection and schizodeme classification of Trypanosoma cruzi by amplification of kinetoplast minicircle DNA sequences: use in the diagnosis of Chagas disease. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1984;33:205–14. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Avila HA, Sigman DS, Coohen LM, Millikan RC, Simpson L. Polymerase chain reaction amplification of Trypanosoma cruzi kinetoplast minicircle DNA isolated from whole blood lysates: diagnosis of chronic Chagas disease. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1991;48:211–22. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Moser DR, Kirchhoff LV, Donelson J. Detection of Trypansoma cruzi by DNA amplification using the polymerase chain reaction. J Clin Microbiol. 1989;27:1477–82.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Fernandes O, Sturm NR, Campbell D. The mini-exon gene: a genetic marker for zymodeme III of Trypanosoma cruzi. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1998;95:129–33. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Briones MR, Souto RP, Stolf BS, Zingales B. The evolution of two Trypanosoma cruzi subgroups inferred from rRNA genes can be correlated with the interchange of American mammalian faunas in the Cenozoic and has implications to pathogenicity and host specificity. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1999;104:219–32. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Souto RP, Zingales B. Sensitive detection and strain classification of Trypanosoma cruzi by amplification of a ribosomal RNA sequence. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1993;63:45–52. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Souto RP, Vargas N, Zingales B. Trypanosoma rangeli: discrimination from Trypanosoma cruzi based on a variable domain from the large subunit ribosomal RNA gene. Exp Parasitol. 1999;91:306–14. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Jorg ME. La modificación del biotopo peri-habitacional en la profilaxis de la enfermedad de Chagas. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 1989;22:91–5.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Vexenat AC, Santana JM, Teixeira ARL. Cross-reactivity of antibodies in human infections by the kinetoplastid protozoa Trypanosoma cruzi, Leishmania chagasi and Leishmania (viannia) braziliensis. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 1996;38:177–85. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Guhl F, Hudson L, Marinkelle CJ, Jaramillo CA, Bridge C. Clinical Trypanosoma rangeli infection as a complication of Chagas disease. Parasitology. 1987;94:475–84. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Romaña CA, Pizarro JC, Rodas E, Guilbert E. Palm trees as ecological indicators of risk areas for Chagas disease. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1999;93:594–5. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Barreto MP, Siqueira AF, Correa FMA, Ferrioli F, Cavalheiro JR. Estudos sobre reservatórios e vetores silvestres do Trypanosoma cruzi. VII: investigacões sobre a infecção natural de gambás por Tripanossomos semelhantes ao "T. cruzi.". Rev Bras Biol. 1964;24:289–300.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Barreto MP, Siqueira AF. Filho, Cavalheiro JR. Estudos sobre reservatórios e vetores silvestres do Trypanosoma cruzi. XI: Observações sobre um foco da tripanosomose Americana no Município de Ribeirão Preto, São Paulo. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 1966;8:103–12.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Barreto MP, Alburquerque RDR, Funayama GK. Estudos sobre reservatórios e vetores silvestres do Trypanosoma cruzi. XXXVI: investigações sobre triatomineos de palmeiras no Municipio De Uberaba, MG, Brasil. Rev Soc Bras Biol. 1969;29:577–88.

- Barreto MP, Ribeiro RD, Rocha GM. Estudos Sobre reservatórios e vetores silvestres do Trypanosoma cruzi. LXIX: Inquérito preliminar sobre triatomíneos silvestres na região do triângulo Mineiro MG, Brasil. Rev Bras Biol. 1978;38:633–7.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Hawksworth DL, Kirk PM, Sutton DN. Dictionary of the fungi. 8th edition. International Mycological Institute. Cambridge: University Press; 1995. p. 76, 272.

- Fungos em plantas no Brasil. Empresa Brasileira de Pesquisa Agropecuária, Centro Nacional de Pesquisa de Recursos Genéticos e Biotecnologia, Ministério da Agricultura e do Abastecimento. Brasília: Serviço de Produção de Informação; 1988. p. 171.

- Edwards PJ, Wratten SD. Ecologia das interações entre insetos e plantas. Vol. 27.São Paulo: Editora Pedagógica e Universitária Ltda; 1981.

- Kempf WW. Levantamento das formigas da mata amazônica, nos arredores de Belém do Pará, Brasil. Studia entomológica. Rio de Janeiro: Vozes Ltda; 1970. p. 321-43.

- Naiff MF, Naiff RD, Barret TV. Vetores selváticos de doença de Chagas na área urbana de Manaus (AM): atividade de vôo nas estações secas e chuvosas. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 1998;31:103–5. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Miles MA, Arias JR, Naiff RD, Souza AA, Povoa MM, Lima JAN, Vertebrate hosts and vectors of Trypanosoma rangeli in the Amazon Basin of Brazil. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1983;32:1251–9.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Helmut S. Birds in Brazil. A natural history. Princeton (NJ): Princeton University Press;1993.

- Deane L. Animal reservoirs of Trypanosoma cruzi in Brazil. Rev Bras Malariol Doencas Trop. 1964;16:28–48.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Deane MP, Jansen AM. Another Trypanosoma, distinct fron T. cruzi, multiples in the lumen of the anal glands of the opossum Didelphis marsupialis. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1986;81:131–2. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Jansen AM, Madeira F, Carreira JC. Acosta-Medina, Deane MP. Trypanosoma cruzi in the opossum Didelphis marsupialis: a study of the correlations and kinetics of the systemic and scent gland infections in naturally and experimentally infected animals. Exp Parasitol. 1997;86:37–44. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Odun EP. Ecologia. Biblioteca Pioneira de Biologia Moderna. São Paulo: Livraria Pioneira; 1977. p. 19-148.

- Morse SS. Factors in the emergence of infectious diseases. Emerg Infect Dis. 1995;1:7–15. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Valente AS, Valente VC, Fraiha Neto A. Considerations on the epidemiology and transmission of Chagas disease in the Brazilian Amazon. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1999;94:395–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Silveira AC, Rezende DF. Epidemiologia e controle da transmissão vetorial da doença de Chagas no Brasil. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop 1994;27(Supl III):11-22.

- Silveira AC, Vinhaes MC. Elimination of vector-borne transmission of Chagas disease. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1999;94:405–11. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Camargo ME, Silva GR, Castilho EA, Silveira AC. Inquérito sorológico da prevalência de infecção chagasica no Brasil, 1985-1980. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 1984;26:192–204.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Dias JCP. A doença de Chagas e seu controle na América Latina. Uma análise de possibilidades. Rio de Janeiro. Cad Saude Publica. 1993;9:201–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Moncayo A. Chagas disease: epidemiology and prospects for interruption of transmission in the Americas. Wld Hlth Statist Quart. 1992;45:276–9.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Valente VC. Potential for domestication of Panstrongylus geniculatus in the municipality of Muaná, Marajó Island, State of Pará, Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1999;94:399–400. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Feitosa VR. Implantação de um sistema de vigilância epidemológica (VE) de doença de Chagas na Amazônia. Ver Soc Brás Méd Trop. 1995;28:84–7.

- Coura JR, Junqueira ACV, Boia MN, Fernandes O. Chagas disease: from bush to huts and houses. Is it the case of the Brazilian Amazon? Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1999;94:379–84. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Bos R. The importance of peridomestic environmental management for the control of the vectors of Chagas disease. Rev Argent Microbiol. 1988;20:58–62.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Kroeger A, Ordonez-Gonzalez J, Behrend M, Alvarez G. Bednet impregnation for Chagas disease control: a new perspective. Trop Med Int Health. 1999;4:194–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Wood E, de Licastro SA, Casabe N, Picollo MI, Alzogaray R, Nicolas Zerba E. A new tactic for Triatoma infestans control: fabrics impregnated with beta-cypermethrin. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 1999;6:1–7. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

1In this study, a major ecosystem is defined as a set of ecoregions of comparable dynamics, response characteristics to disturbance, species diversity, and conservation needs. An ecoregion is a geographically distinct set of natural communities with similar species, ecologic dynamics, environmental conditions, and ecologic interactions critical for long-term persistence (1).