Volume 26, Number 11—November 2020

Research

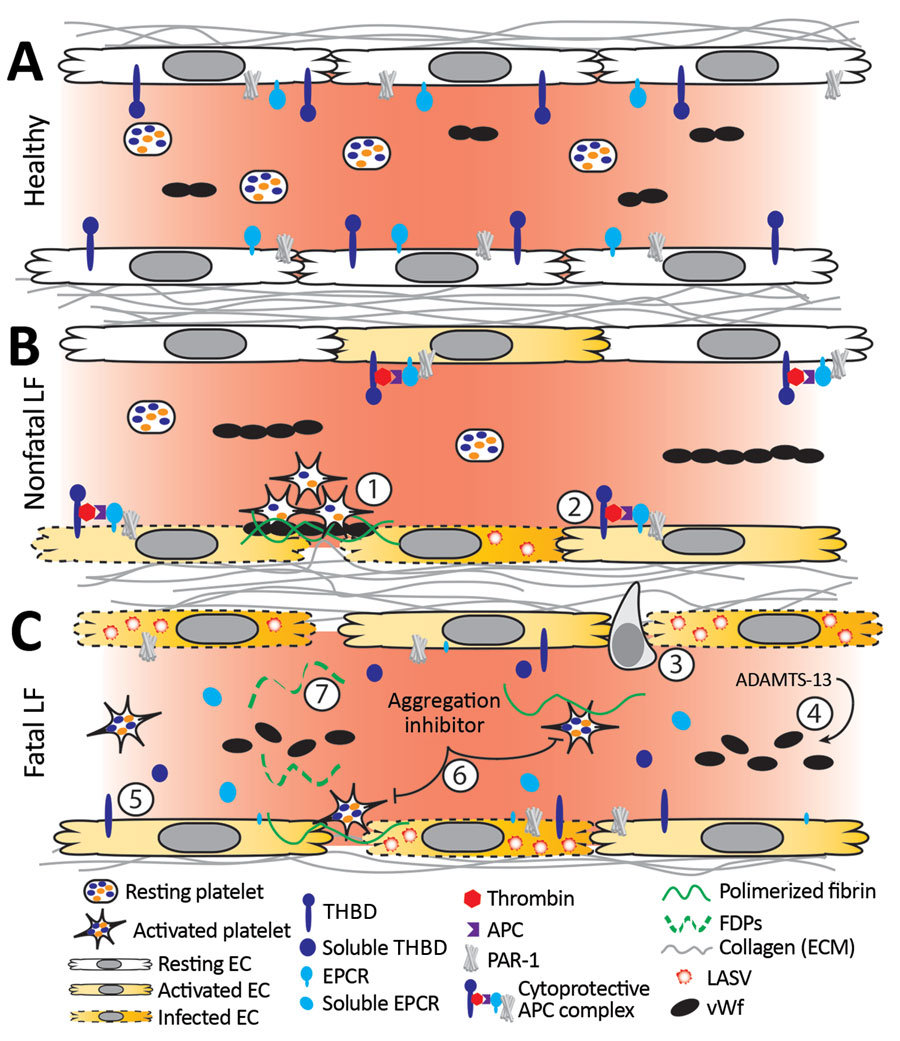

Endotheliopathy and Platelet Dysfunction as Hallmarks of Fatal Lassa Fever

Figure 8

Figure 8. Working model of endothelial barrier function during time-of-admission for Lassa fever showing differences in function between healthy endothelium, and endothelium in nonfatal and fatal Lassa fever, Sierra Leone during 2015–2018. A) Healthy endothelium; resting platelets circulate and lower molecular weight vWF multimers are constitutively secreted by the endothelium. B) Endothelium barrier function in non-fatal Lassa fever. 1) Immune mediated damage near infected endothelial cells leads to collagen exposure, fibrin deposition, platelet activation, endothelial activation, and release of ultra-high molecular weight vWF from endothelial cells and platelets. Functional coagulation and platelet responses lead to endothelial repair. 2) Endothelial surface bound thrombomodulin and EPCR lead to activation of protein C; PAR-1 activation strengthens endothelial tight junctions, increases endothelial survival, and dampens the inflammatory response. C) Endothelium barrier function in fatal Lassa fever. 3) Increased endothelial infection has been observed in fatal LF cases. Increased immune infiltrates likely stress the endothelial barrier and lead to increased endothelial activation, evidenced by increased soluble ICAM, P-selectin, and EPCR. 4) Ultra-high molecular weight vWF multimers are broken down by ADAMTS-13, likely leading to the increased vWF ELISA signal observed during fatal LF. 5) Increases in soluble thrombomodulin and EPCR likely leave less surface bound forms, inhibiting the ability of endothelial cells to activate cytoprotective pathways through PAR-1 and increasing their susceptibility to immune mediated destruction. 6) Our in vitro aggregation studies show that platelets in the presence of the aggregation inhibitor become activated and change shape in response to platelet agonists but fail to maintain the aggregated state. These data are consistent with the inhibition of the release of α or dense granules or their contents, thereby inhibiting certain aspects of primary hemostasis, clot formation, and endothelial repair. 7) The state of fibrinolysis during fatal LF is unclear. Increased PAI-1 suggests an inhibition of fibrinolysis, but D-dimers and other FDPs are only formed during plasmin mediated breakdown of fibrin. Likely, increased platelet activation leads to an increase of total fibrin formation. Platelet dysfunction can lead to weaker hemostatic plugs which then leave fibrin more susceptible to cleavage by plasmin. APC, activated protein C; EC, endothelial cell; EPCR, endothelial protein C receptor; FDP, fibrin degradation product; ICAM, intercellular adhesion molecule; LASV, Lassa fever virus; PAI-1, plasminogen activator inhibitor 1; PAR-1, protease-activated receptor 1; plasminogen activator inhibitor 1; THBD, thrombomodulin; vWF, von Willebrand factor.

1These authors contributed equally to this article.