Volume 29, Number 10—October 2023

Dispatch

Angiostrongylus cantonensis Infection in Brown Rats (Rattus norvegicus), Atlanta, Georgia, USA, 2019–2022

Cite This Article

Citation for Media

Abstract

Rat lungworm (Angiostrongylus cantonensis), a zoonotic parasite invasive to the United States, causes eosinophilic meningoencephalitis. A. cantonensis harbors in rat reservoir hosts and is transmitted through gastropods and other paratenic hosts. We discuss the public health relevance of autochthonous A. cantonensis cases in brown rats (Rattus norvegicus) in Atlanta, Georgia, USA.

Rat lungworm, Angiostrongylus cantonensis (Strongylida: Metastrongyloidea), causes eosinophilic meningoencephalitis (neural angiostrongyliasis) in humans and other accidental mammal hosts. This vectorborne nematode has an indirect life cycle in which several rodent species, including Rattus spp., serve as definitive hosts (1). Rodents become infected by ingesting terrestrial gastropods acting as intermediate hosts infected with third-stage larvae (L3). In the rodent host, L3 migrate through vasculature to the central nervous system and after 2 molts become adult nematodes that migrate to the pulmonary artery (1). After mating, females lay eggs that hatch first-stage larvae (L1) in lung airspaces. L1 ascend the trachea, pass into the digestive system after being swallowed by the host rat, and exit the body through feces (1). Subsequently, gastropods ingest nematode L1 after which the larvae develop to the infective L3 stage. Paratenic hosts, such as fish, frogs, and crustaceans, can also harbor A. cantonensis L3, which can be transferred to rodents and accidental hosts (2).

A. cantonensis, originally described in Asia, where most human infections are reported, is now endemic in different regions of the world (2). In the United States, A. cantonensis was initially reported in Hawaii (3), and later in Texas, Louisiana, Alabama, and Florida, likely introduced by infected rats and gastropods through trade routes, such as on merchant ships (3–7). We confirm autochthonous A. cantonensis infection in brown rats (Rattus norvegicus) in Atlanta, Georgia, USA, and briefly discuss the relevance of these findings to human and animal health.

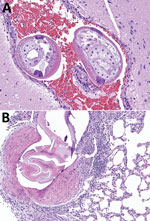

We collected tissue samples (brain, heart, liver, kidney, lung, spleen, skeletal muscle, skin, gastrointestinal tract, adrenal gland, and gonads) from 33 wild brown rats found dead during 2019–2022 on the grounds of a zoological facility located in Atlanta, Fulton County, Georgia (33°44′1.536″N; 84°22′19.416″W). We stored samples in 10% neutral buffered formalin and processed them for routine histopathologic evaluation as part of opportunistic monitoring of wildlife found dead on zoo grounds. Of the rats we histologically evaluated, 7/33 (21.2%) had nematodes in heart, pulmonary artery, and brain tissues (Table; Figure).

Where intravascular nematodes were observed, we extracted genomic DNA from paraffin-embedded tissue sections using QIAamp DNA FFPE Tissue Kit (QIAGEN, https://www.qiagen.com) according to manufacturer recommendations. PCR reactions targeted a 200-bp segment of the mitochondrial cytochrome oxidase subunit 1 gene (cox1). We performed a 25 μL reaction containing 0.25 μmol each of primers CO1ACF7 (5′-TGCCTGCTTTTGGGATTGTTAGAC-3′) and CO1ACR7 (5′-TCACTCCCGTAGGAACCGCA-3′), 1× GoTaq Green Master Mix (Promega Corporation, https://www.promega.com), and 2.5 μL of DNA template (8). Cycling procedure involved initial denaturation at 95°C for 2 min, then 40 cycles at 95°C for 30 s, 50°C for 30 s, 72°C for 90 s, and a final extension at 72°C for 5 min. We used nuclease-free water as a negative control and DNA of Dirofilaria immitis as a positive control. We purified PCR products using the EZNA Cycle Pure Kit (OMEGA Bio-Tek, https://www.omegabiotek.com) according to manufacturer instructions. We aligned and compared generated sequences with homologous A. cantonensis sequences available in GenBank. We determined genetic distances and performed phylogenetic analysis using MEGA X 10.1 (9) (Table).

Our molecular analysis confirmed the identity of A. cantonensis in 4/7 samples that had nematodes visible on histologic examination of heart, pulmonary artery, and brain tissues (Table). All 4 sequences were 100% identical to each other and to A. cantonensis sequences belonging to haplotype 17a, previously reported from Louisiana, USA. Among homologous sequences available in GenBank from A. cantonensis isolates from the United States, those belonging to haplotype 17b (Louisiana and California) were 99.5% similar, haplotype 8b (Louisiana) 98.9% similar, and haplotype 5a (Hawaii) 98.9% similar to those in haplotype 17a. Overall, compared with other A. cantonensis haplotypes included in the phylogenetic analysis, similarity of sequences ranged from 93.1%–99.5%, clustering in a clade with 86% bootstrap support (Appendix).

Discovery of autochthonous cases of A. cantonensis infection in definitive host rodents collected during 2019–2022 in the state of Georgia, suggests that this zoonotic parasite was introduced to and has become established in a new area of the southeastern United States. Although we molecularly confirmed diagnosis in only 4/7 cases, the remaining rats had intravascular nematodes morphologically consistent with A. cantonensis and typical associated lesions. We could not molecularly confirm the remaining 3 cases because of insufficient sample quality and DNA degradation; thus, we could not rule out the presence of other nematode species.

Because A. cantonensis lungworm previously was identified in rats in neighboring states Florida and Alabama, A. cantonensis populations likely were in Georgia much earlier than 2019, when the first positive rat was identified in Atlanta. Furthermore, 6 suspected autochthonous human angiostrongyliasis cases were detected during 2011–2017 in Texas, Tennessee, and Alabama (10). Among captive wildlife, A. cantonensis lungworm has been reported in nonhuman primates in Florida (11), Louisiana (7,12), Texas (4), and Alabama (13), and a red kangaroo in Mississippi (14). Among free-ranging wildlife native to the southeastern United States, A. cantonensis infections have been identified in armadillos and an opossum (15).

Various native and exotic gastropod species have been shown, both naturally and experimentally, to be susceptible intermediate hosts (3,5,11). Although details of A. cantonensis invasion and spread are not fully known, identification of introduced gastropods as intermediate hosts (11) and Cuban tree frogs as paratenic hosts (6) in the southern United States suggest anthropogenic disturbance and climate-induced change in local food webs might be amplifying A. cantonensis transmission. Clearly, A. cantonensis lungworm in urban rat populations, gastropod intermediate hosts, and other paratenic hosts in the populous greater Atlanta area pose a possible threat to the health of humans and domestic, free-ranging, and captive animals.

Understanding patterns of historic, contemporary, and future expansion of the range of A. cantonensis lungworm in North America through surveillance, genetic analysis, and modeling is critical to mitigating risk to humans and other animals for infection by this parasitic nematode, which harbors in synanthropic wild rodent and intermediate host populations. Medical and veterinary professionals throughout the southern United States should consider A. cantonensis infection in differential diagnoses of aberrant central nervous system larva migrans, eosinophilic meningitis, and meningoencephalitis.

Dr. Gottdenker is a professor in the Department of Pathology at the University of Georgia College of Veterinary Medicine, Athens, GA, USA. Her research focuses on pathology and ecology of wildlife diseases, including zoonotic parasites, and the effects of anthropogenic environmental changes on disease ecology and evolution.

References

- da Silva AJ, Morassutti AL. Angiostrongylus spp. (Nematoda; Metastrongyloidea) of global public health importance. Res Vet Sci. 2021;135:397–403. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Wang QP, Lai DH, Zhu XQ, Chen XG, Lun ZR. Human angiostrongyliasis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2008;8:621–30. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Stockdale Walden HD, Slapcinsky JD, Roff S, Mendieta Calle J, Diaz Goodwin Z, Stern J, et al. Geographic distribution of Angiostrongylus cantonensis in wild rats (Rattus rattus) and terrestrial snails in Florida, USA. PLoS One. 2017;12:

e0177910 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Edwards EE, Borst MM, Lewis BC, Gomez G, Flanagan JP. Angiostrongylus cantonensis central nervous system infection in captive callitrichids in Texas. Vet Parasitol Reg Stud Rep. 2020;19:

100363 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Cowie RH, Ansdell V, Panosian Dunavan C, Rollins RL. Neuroangiostrongyliasis: global spread of an emerging tropical disease. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2022;107:1166–72. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Chase EC, Ossiboff RJ, Farrell TM, Childress AL, Lykins K, Johnson SA, et al. Rat lungworm (Angiostrongylus cantonensis) in the invasive Cuban treefrog (Osteopilus septentrionalis) in central Florida, USA. J Wildl Dis. 2022;58:454–6. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Rizor J, Yanez RA, Thaiwong T, Kiupel M. Angiostrongylus cantonensis in a red ruffed lemur at a zoo, Louisiana, USA. Emerg Infect Dis. 2022;28:1058–60. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Qvarnstrom Y, Xayavong M, da Silva ACA, Park SY, Whelen AC, Calimlim PS, et al. Real-time polymerase chain reaction detection of Angiostrongylus cantonensis DNA in cerebrospinal fluid from patients with eosinophilic meningitis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2016;94:176–81. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Kumar S, Stecher G, Li M, Knyaz C, Tamura K. MEGA X: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Mol Biol Evol. 2018;35:1547–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Liu EW, Schwartz BS, Hysmith ND, DeVincenzo JP, Larson DT, Maves RC, et al. Rat lungworm infection associated with central nervous system disease—eight U.S. states, January 2011–January 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:825–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Walden HDS, Slapcinsky J, Rosenberg J, Wellehan JFX. Angiostrongylus cantonensis (rat lungworm) in Florida, USA: current status. Parasitology. 2021;148:149–52. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Gardiner CH, Wells S, Gutter AE, Fitzgerald L, Anderson DC, Harris RK, et al. Eosinophilic meningoencephalitis due to Angiostrongylus cantonensis as the cause of death in captive non-human primates. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1990;42:70–4. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Kottwitz JJ, Perry KK, Rose HH, Hendrix CM. Angiostrongylus cantonensis infection in captive Geoffroy’s tamarins (Saguinus geoffroyi). J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2014;245:821–7. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Patial S, Delcambre BA, DiGeronimo PM, Conboy G, Vatta AF, Bauer R. Verminous meningoencephalomyelitis in a red kangaroo associated with Angiostrongylus cantonensis infection. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2022;34:107–11. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Dalton MF, Fenton H, Cleveland CA, Elsmo EJ, Yabsley MJ. Eosinophilic meningoencephalitis associated with rat lungworm (Angiostrongylus cantonensis) migration in two nine-banded armadillos (Dasypus novemcinctus) and an opossum (Didelphis virginiana) in the southeastern United States. Int J Parasitol Parasites Wildl. 2017;6:131–4. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

Figure

Table

Cite This ArticleTable of Contents – Volume 29, Number 10—October 2023

| EID Search Options |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Please use the form below to submit correspondence to the authors or contact them at the following address:

Guilherme G. Verocai, Texas A&M University College of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences, Veterinary Pathobiology, 660 Raymond Stotzer Pkwy, College Station, TX 77843, USA

Top