Volume 31, Number 11—November 2025

Research

Two Independent Acquisitions of Multidrug Resistance Gene lsaC in Streptococcus pneumoniae Serotype 20 Multilocus Sequence Type 1257

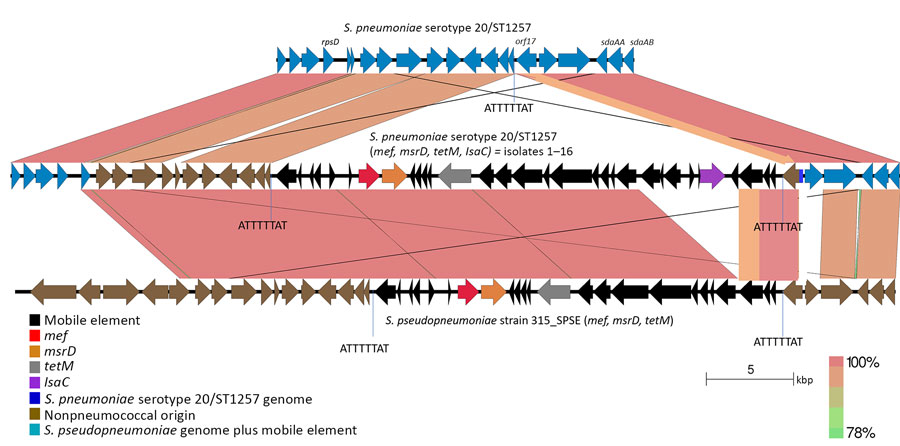

Figure 4

Figure 4. Near sequence identity shared between pneumococcal isolates 1–16 and Streptococcus pseudopneumoniae strain 315_SPE in mobile element insertion region in study of 2 independent acquisitions of multidrug resistance gene lsaC in serotype 20/ST1257 S. pneumoniae, United States. The near-identical region includes much of the mobile element itself, and flanking genes that diverge from pneumococcal parental recipient strain (top). The EasyFig (20) output homology was modified to reflect boundaries between marked homology differences between the 2 pneumococcal strains (focused upon orf17 only) and between the middle pneumococcal strain and the below S. pseudopneumoniae strain (encompassing the last 3 orfs of the mobile elements and most of orf17). ST, sequence type.

References

- Schroeder MR, Stephens DS. Macrolide resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2016;6:98. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Murphy PB, Bistas KG, Patel P, Le JK. Clindamycin. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 [cited 2024 Feb 28]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519574

- de Azavedo JC, McGavin M, Duncan C, Low DE, McGeer A. Prevalence and mechanisms of macrolide resistance in invasive and noninvasive group B streptococcus isolates from Ontario, Canada. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2001;45:3504–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Achard A, Villers C, Pichereau V, Leclercq R. New lnu(C) gene conferring resistance to lincomycin by nucleotidylation in Streptococcus agalactiae UCN36. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49:2716–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Malbruny B, Werno AM, Murdoch DR, Leclercq R, Cattoir V. Cross-resistance to lincosamides, streptogramins A, and pleuromutilins due to the lsa(C) gene in Streptococcus agalactiae UCN70. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:1470–4. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Douarre PE, Sauvage E, Poyart C, Glaser P. Host specificity in the diversity and transfer of lsa resistance genes in group B Streptococcus. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2015;70:3205–13. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Schwarz S, Shen J, Kadlec K, Wang Y, Brenner Michael G, Feßler AT, et al. Lincosamides, streptogramins, phenicols, and pleuromutilins: mode of action and mechanisms of resistance. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2016;6:

a027037 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - US Food and Drug Administration. Xenleta: highlights of prescribing information [cited 2019 Sep 16]. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2019/211672s000,211673s000lbl.pdf

- Cao Y, Zhu J, Liang B, Guo Y, Ding L, Hu F. Assessment of lefamulin 20 µg disk versus broth microdilution when tested against common respiratory pathogens. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2024;64:

107366 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing, 34th ed (M100-S34). Wayne, PA: The Institute; 2024.

- ABCs Bactfacts Interactive Data Dashboard. Active bacterial core surveillance reports for 1997–2021 [cited 2024 Oct 13]. https://www.cdc.gov/abcs/bact-facts/data-dashboard.html

- Metcalf BJ, Gertz RE Jr, Gladstone RA, Walker H, Sherwood LK, Jackson D, et al.; Active Bacterial Core surveillance team. Strain features and distributions in pneumococci from children with invasive disease before and after 13-valent conjugate vaccine implementation in the USA. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2016;22:60.e9–29. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Metcalf BJ. CDC streptococcal bioinformatics pipelines [cited 2023 Dec 1]. https://github.com/BenJamesMetcalf

- Chochua S, Beall B, Lin W, Tran T, Rivers J, Li Z, et al. The emergent invasive serotype 4 ST10172 strain acquires vanG type vancomycin resistance element: a case of a 66-year-old with bacteremic pneumococcal pneumonia. J Infect Dis. 2025;231:746–50. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Paukner S, Riedl R. Pleuromutilins: potent drugs for resistant bugs—mode of action and resistance. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2017;7:

a027110 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Kolmogorov M, Yuan J, Lin Y, Pevzner PA. Assembly of long, error-prone reads using repeat graphs. Nat Biotechnol. 2019;37:540–6. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Lin Y, Yuan J, Kolmogorov M, Shen MW, Chaisson M, Pevzner PA. Assembly of long error-prone reads using de Bruijn graphs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:E8396–405. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Camacho C, Coulouris G, Avagyan V, Ma N, Papadopoulos J, Bealer K, et al. BLAST+: architecture and applications. BMC Bioinformatics. 2009;10:421. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Seemann T. Prokka: rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2068–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Sullivan MJ, Petty NK, Beatson SA. Easyfig: a genome comparison visualizer. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:1009–10. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Gardner SN, Slezak T, Hall BG. kSNP3.0: SNP detection and phylogenetic analysis of genomes without genome alignment or reference genome. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:2877–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K. MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol Biol Evol. 2016;33:1870–4. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Grant JR, Enns E, Marinier E, Mandal A, Herman EK, Chen C, et al. Proksee: in-depth characterization and visualization of bacterial genomes nucleic acids research. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023;51(W1):

W484–92 . - Brown CL, Mullet J, Hindi F, Stoll JE, Gupta S, Choi M, et al. mobileOG-db: a manually curated database of protein families mediating the life cycle of bacterial mobile genetic elements. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2022;88:

e0099122 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Darling AE, Mau B, Perna NT. progressiveMauve: multiple genome alignment with gene gain, loss and rearrangement. PLoS One. 2010;5:

e11147 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Croucher NJ, Page AJ, Connor TR, Delaney AJ, Keane JA, Bentley SD, et al. Rapid phylogenetic analysis of large samples of recombinant bacterial whole genome sequences using Gubbins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:

e15 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Clewell DB, Flannagan SE, Jaworski DD, Clewell DB. Unconstrained bacterial promiscuity: the Tn916-Tn1545 family of conjugative transposons. Trends Microbiol. 1995;3:229–36. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Metcalf BJ, Chochua S, Walker H, Tran T, Li Z, Varghese J, et al. Invasive pneumococcal strain distributions and isolate clusters associated with persons experiencing homelessness during 2018. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;72:e948–56. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Beall B, Chochua S, Li Z, Tran T, Varghese J, McGee L, et al. Invasive pneumococcal disease clusters disproportionally impact persons experiencing homelessness, injecting drug users, and the western United States. J Infect Dis. 2022;226:332–41. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Glambek M, Skrede S, Sivertsen A, Kittang BR, Kaci A, Jonassen CM, et al.; Norwegian Study Group on Streptococcus dysgalactiae. Antimicrobial resistance patterns in Streptococcus dysgalactiae in a One Health perspective. Front Microbiol. 2024;15:

1423762 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - D’Aeth JC, van der Linden MP, McGee L, de Lencastre H, Turner P, Song J-H, et al.; GPS Consortium. The role of interspecies recombination in the evolution of antibiotic-resistant pneumococci. Elife. 2021;10:

e67113 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Beall B, Chochua S, Metcalf B, Lin W, Tran T, Li Z, et al. Increased proportions of invasive pneumococcal disease cases among adults experiencing homelessness sets stage for new serotype 4 capsular-switch recombinant. J Infect Dis. 2025;231:871–82. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Beall B, Walker H, Tran T, Li Z, Varghese J, McGee L, et al. Upsurge of conjugate vaccine serotype 4 invasive pneumococcal disease clusters among adults experiencing homelessness in California, Colorado, and New Mexico. J Infect Dis. 2021;223:1241–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Sankilampi U, Honkanen PO, Bloigu A, Leinonen M. Persistence of antibodies to pneumococcal capsular polysaccharide vaccine in the elderly. J Infect Dis. 1997;176:1100–4. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Kobayashi M, Leidner AJ, Gierke R, Farrar JL, Morgan RL, Campos-Outcalt D, et al. Use of 21-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine among U.S. adults: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, 2024. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2024;73:793–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Huang SS, Hinrichsen VL, Stevenson AE, Rifas-Shiman SL, Kleinman K, Pelton SI, et al. Continued impact of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine on carriage in young children. Pediatrics. 2009;124:e1–11. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Sharma D, Baughman W, Holst A, Thomas S, Jackson D, da Gloria Carvalho M, et al. Pneumococcal carriage and invasive disease in children before introduction of the 13-valent conjugate vaccine: comparison with the era before 7-valent conjugate vaccine. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2013;32:e45–53. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Desai AP, Sharma D, Crispell EK, Baughman W, Thomas S, Tunali A, et al. Decline in pneumococcal nasopharyngeal carriage of vaccine serotypes after the introduction of the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in children in Atlanta, Georgia. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2015;34:1168–74. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Milucky J, Carvalho MG, Rouphael N, Bennett NM, Talbot HK, Harrison LH, et al.; Adult Pneumococcal Carriage Study Group. Streptococcus pneumoniae colonization after introduction of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine for US adults 65 years of age and older, 2015-2016. Vaccine. 2019;37:1094–100. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Kellner JD, McGeer A, Cetron MS, Low DE, Butler JC, Matlow A, et al. The use of Streptococcus pneumoniae nasopharyngeal isolates from healthy children to predict features of invasive disease. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1998;17:279–86. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Metcalf BJ, Waldetoft KW, Beall BW, Brown SP. Variation in pneumococcal invasiveness metrics is driven by serotype carriage duration and initial risk of disease. Epidemics. 2023;45:

100731 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Domínguez-Hüttinger E, Boon NJ, Clarke TB, Tanaka RJ. Mathematical modeling of Streptococcus pneumoniae colonization, invasive infection and treatment. Front Physiol. 2017;8:115. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Pilishvili T, Lexau C, Farley MM, Hadler J, Harrison LH, Bennett NM, et al.; Active Bacterial Core Surveillance/Emerging Infections Program Network. Sustained reductions in invasive pneumococcal disease in the era of conjugate vaccine. J Infect Dis. 2010;201:32–41. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Ahmed SS, Pondo T, Xing W, McGee L, Farley M, Schaffner W, et al. Early impact of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine use on invasive pneumococcal disease among adults with and without underlying medical conditions—United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;70:2484–92. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- US Department of Housing and Urban Development. Annual homelessness assessment report [cited 2025 Sep 26]. https://www.huduser.gov/portal/datasets/ahar.html

- Kellner JD, Ricketson LJ, Demczuk WHB, Martin I, Tyrrell GJ, Vanderkooi OG, et al. Whole-genome analysis of Streptococcus pneumoniae serotype 4 causing outbreak of invasive pneumococcal disease, Alberta, Canada. Emerg Infect Dis. 2021;27:1867–75. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Navajo Epidemiology Center. Serotype 4 invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) information for providers [cited 2024 Jul 22]. https://nec.navajo-nsn.gov/Projects-Reports/Infectious-Disease

- Golubchik T, Brueggemann AB, Street T, Gertz RE Jr, Spencer CC, Ho T, et al. Pneumococcal genome sequencing tracks a vaccine escape variant formed through a multi-fragment recombination event. Nat Genet. 2012;44:352–5. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar