Volume 31, Number 5—May 2025

Research Letter

Autochthonous Leishmania (Viannia) lainsoni in Dog, Rio de Janeiro State, Brazil, 2023

Abstract

In Brazil, Leishmania (Leishmania) infantum causes canine visceral leishmaniasis; the primary vector is the Lutzomyia longipalpis sand fly. We describe a case of canine visceral leishmaniasis caused by Leishmania (Viannia) lainsoni in a dog from Barra Mansa municipality, Rio de Janeiro state. Better specificity of serologic diagnostic techniques is needed for diagnoses.

Protozoa transmitted by sand flies cause leishmaniasis, and several pathogenic species affect humans. Various clinical forms of the disease have been described, including visceral, cutaneous, and mucocutaneous leishmaniasis (1). Leishmania (Viannia) lainsoni was described in Brazil in 1987 as the causative agent of human cases of cutaneous leishmaniasis. Its vector is the Lutzomyia ubiquitalis sand fly (2). Other countries in Latin America have reported human cases of L. (V.) lainsoni infection. Researchers isolated the parasite from the rodent species Cuniculus paca, the lowland paca, in the state of Pará, Brazil, suggesting a potential wild reservoir (3,4).

This study reports the case of a dog (Canis familiaris) infected with L. (V.) lainsoni that was from the municipality of Barra Mansa, an urban area in Rio de Janeiro state with widespread visceral leishmaniasis (VL) (Appendix). The Ethics Committee on the Use of Animals–Fiocruz approved this work (license no. LW 19/20; https://www.ceua.fiocruz.br/ceuaw000.aspx).

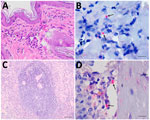

A 5-year-old male dog of mixed breed domiciled in Barra Mansa tested positive for VL by both rapid immunochromatographic testing and enzyme immunoassay (Bio-Manguinhos, https://portal.fiocruz.br/en/unidade/immunobiological-technology-institute-biomanguinhos) during epidemiologic surveillance in 2023 and was euthanized using the recommendations of the Brazilian Ministry of Health (https://www.gov.br). The dog had not moved to other regions and had localized alopecia, crusted skin ulcers, onychogryphosis, keratoconjunctivitis, normocytic normochromic anemia, hyperproteinemia, hyperglobulinemia, hypoalbuminemia, and a low albumin:globulin ratio (Appendix). Histopathologic changes included skin with hyperkeratosis and multifocal and moderate granulomatous dermatitis, as well as lymphoid hyperplasia of the spleen. Immunohistochemistry was positive for amastigote forms of Leishmania in skin and spleen (Figure 1).

We performed parasitologic and PCR tests (Appendix Table 2). We used multilocus enzyme electrophoresis with 5 enzyme profiles (phosphoglucomutase, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase, nucleoside hydrolase, 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase, and phosphoglucose isomerase) (5). We extracted DNA from the isolated parasite and used it for PCR restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis (HaeIII and BstUI). We sequenced the 70-kDa heat shock protein products with the same primers by Sanger sequencing (primers: BankIt2825220 and Seq1PP760383) (6). Those techniques identified the parasite as L. (V.) lainsoni in all profiles studied in the bone marrow sample (Figure 2).

Like other species of the subgenus Viannia, L. (V.) lainsoni can cause ulcerative or nodular dermal lesions in humans (4). The clinical signs found in this infected dog included onychogryphosis and skin alterations. Development of skin lesions can lead to hematogenous dissemination and parasitemia of internal organs, as observed in this case, and visceral involvement of lymph nodes and spleen (7). The positive results of serologic tests show flaws in the specificity of the techniques because those tests were validated for detecting dogs with canine VL caused by L. (Leishmania) infantum. Hematocrit values less than the reference range, along with a slight increase in total protein, are expected in chronic diseases. We observed no changes in renal function markers. The host–parasite interaction has been extensively studied in dogs infected with L. (L.) infantum; however, little is known about that interaction in dogs infected with other Leishmania species.

In Latin America, L. (V.) lainsoni is found in tropical and sub-Andean regions with different climatic conditions. Its presence in other countries highlights the high dispersal capacity of the parasite and potential involvement of unidentified mammalian host vectors. Barra Mansa has a crucial migratory flow because it is located on the banks of the Paraíba do Sul River and influences the Médio Paraíba region and southern part of the south-central region of Rio de Janeiro State.

The dog lived in an area surrounded by natural and abundantly wooded areas. A large portion of the Hemlock Forest is located in Barra Mansa, and C. paca rodents are part of the local fauna and could serve as reservoirs of L. (V.) lainsoni in that area (8).

Few entomologic surveys have been conducted in Barra Mansa, and only Lu. sallesi and Lu. longipalpis sand flies were confirmed, limiting the conclusions of this study (9). Although the Lu. ubiquitalis sand fly is considered the primary vector of L. (V.) lainsoni in Brazil, other species such as Lu. nuneztovari anglesi and Lu. velascoi sand flies in Bolivia have been reported (10). Therefore, identification of a dog infected with L. (V.) lainsoni in Barra Mansa may be linked to transmission by other yet undocumented sand fly species in that municipality. The dog did not have a history of moving to other locations. We consider environmental changes caused by humans in the region, as well as local wildlife and migratory flows, as possible causes of infection. This study raises several questions. Is a new and yet unknown disease cycle being established locally? What is the risk for the disease becoming endemic in the population? Will the cycle persist? Also, could other regions in Brazil or elsewhere face similar risks of emerging Leishmania species infecting dogs? Further epidemiologic investigations and taxonomic characterization studies are essential and should be continuously supported. Efforts to create clearer specificity in serologic diagnostic techniques are also needed.

Ms. Santos is a PhD student at the Instituto Nacional de Infectologia Evandro Chagas, Fundação Oswaldo Cruz, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Her research interests include the evaluation of diagnostic techniques for dogs suspected of having canine visceral leishmaniasis, using molecular techniques such as conventional PCR, quantitative PCR, and loop-mediated isothermal amplification.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Municipal Health Department of Barra Mansa and the Central Laboratory of Public Health for collaboration and Adilson Benedito de Almeida and Ricardo Baptista Schmidt for processing the figures.

This study was supported by Fundação Carlos Chagas Filho de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (grant no. CNE-E-26/201.032/2021) and Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior, Brazil (finance code 001). R.C. Menezes is a recipient of productivity fellowships from Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Cientifico e Tecnológico, Brazil (grant no. 305956/2021-3).

A.P.M., D.M.d.A., and R.C.M. conceptualized the study. I.C.d.S.S., D.M.d.A, L.d.F.C.M., A.A.V.M.J., L.K.O., L.d.S.V., A.F.d.S., F.N.S., L.d.F.A.O., R.C.M., and A.P.M. constructed the methodology. I.C.d.S.S., D.M.d.A, L.F.C.M., A.A.V.M.J., L.K.O., L.d.S.V., and F.N.S. carried out the investigation. R.C.M., A.F.d.S., L.d.F.A.O., and A.P.M. performed data analysis. A.P.M. and R.C.M. acquired funding. A.P.M. was the study administrator. R.C.M. supervised the study. I.C.d.S.S. and A.P.M. wrote the original draft. All authors contributed to the review and editing of the final manuscript.

References

- World Health Organization. Leishmaniasis [cited 2024 Jul 2]. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/leishmaniasis

- Silveira FT, Shaw JJ, Braga RR, Ishikawa E. Dermal leishmaniasis in the Amazon region of Brazil: Leishmania (Viannaia) lainsoni sp.n., a new parasite from the State of Pará. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1987;82:289–91. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Silveira FT, Lainson R, Shaw JJ, Braga RR, Ishikawa EE, Souza AA. [Cutaneous leishmaniasis in Amazonia: isolation of Leishmania (Viannia) lainsoni from the rodent Agouti paca (Rodentia: Dasyproctidae), in the state of Pará, Brazil] [in Portuguese]. Rev Inst Med Trop São Paulo. 1991;33:18–22. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Corrêa JR, Brazil RP, Soares MJ. Leishmania (Viannia) lainsoni (Kinetoplastida: Trypanosomatidae), a divergent Leishmania of the Viannia subgenus—a mini review. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2005;100:587–92. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Cupolillo E, Grimaldi G Jr, Momen H. A general classification of New World Leishmania using numerical zymotaxonomy. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1994;50:296–311. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Graça GC, Volpini AC, Romero GAS, Oliveira Neto MP, Hueb M, Porrozzi R, et al. Development and validation of PCR-based assays for diagnosis of American cutaneous leishmaniasis and identification of the parasite species. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2012;107:664–74. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Marquez ES, de Castro EA, Nabut LB, da Costa-Ribeiro MCV, Dela Coletta Troiano Araújo L, Poubel SB, et al. Cutaneous leishmaniosis in naturally infected dogs in Paraná, Brazil, and the epidemiological implications of Leishmania (Viannia) braziliensis detection in internal organs and intact skin. Vet Parasitol. 2017;243:219–25. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Brasil, Ministério do Meio Ambiente. Plano de manejo ARIE floresta da cicuta [cited 2024 Jul 16]. https://www.gov.br/icmbio/pt-br/assuntos/biodiversidade/unidade-de-conservacao/unidades-de-biomas/mata-atlantica/lista-de-ucs/arie-floresta-da-cicuta/arquivos/plano-de-manejo-arie-cicuta-oficial.pdf

- Carvalho BM, Dias CMG, Rangel EF. Phlebotomine sand flies (Diptera, Psychodidae) from Rio de Janeiro state, Brazil: species distribution and potential vectors of leishmaniasis. Rev Bras Entomol. 2014;58:77–87. DOIGoogle Scholar

- Kato H, Cáceres AG, Mimori T, Ishimaru Y, Sayed ASM, Fujita M, et al. Use of FTA cards for direct sampling of patients’ lesions in the ecological study of cutaneous leishmaniasis. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48:3661–5. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

Figures

Cite This ArticleOriginal Publication Date: April 15, 2025

1These authors contributed equally to this article.

Table of Contents – Volume 31, Number 5—May 2025

| EID Search Options |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Please use the form below to submit correspondence to the authors or contact them at the following address:

Andreza Pain Marcelino, Laboratório de Pesquisa Clínica e Vigilância em leishmanioses, Instituto Nacional de Infectologia Evandro Chagas, Fundação Oswaldo Cruz, 4365 Brasil Ave, Manguinhos, Rio de Janeiro 21040-900, Brazil

Top