Volume 31, Number 5—May 2025

Dispatch

Recent and Forecasted Increases in Coccidioidomycosis Incidence Linked to Hydroclimatic Swings, California, USA

Cite This Article

Citation for Media

Abstract

In 2023, California reported near–record high coccidioidomycosis cases after a dramatic transition from drought to heavy precipitation. Using an ensemble model, we forecasted 12,244 cases statewide during April 1, 2024–March 31, 2025, a 62% increase over cases reported 2 years before and on par with case counts for 2023.

Incidence of coccidioidomycosis, an emerging infectious disease caused by Coccidioides spp. fungi, has increased dramatically since 2000 (1). In 2023, California, USA, reported a near-record 9,054 coccidioidomycosis cases (only surpassed by 9,093 cases in 2019). During April 2023–March 2024, a period capturing the full seasonal rise and fall in incidence, California reported 10,519 cases, 39% higher than the same period the previous year (2).

The 2023 spike in incidence might be attributable, in part, to a swing from extreme drought to heavy precipitation during winter 2022–2023. Transitions from dry to wet years have been linked to increased coccidioidomycosis incidence (3,4). Soil moisture during wet winters is hypothesized to support fungal growth, contributing to an abundance of spores available for airborne dispersal during hot, dry conditions characteristic of summer and early fall (3). Drought preceding rainy seasons might enhance fungal growth by eliminating microbial competitors from soils (5) or by affecting rodent populations, a putative reservoir host and nutrient source for the fungus (6). During 2020–2022, California experienced severe drought (7). An unusually wet winter followed in 2022–2023; statewide precipitation exceeded 150% of average, among the top 10 wettest seasons in the past century (7). Statewide precipitation during the 2023–2024 wet season was 115% of the long-term average, marking the second consecutive wetter-than-average season after a severe drought (7). That pattern suggested high coccidioidomycosis incidence might continue throughout the 2024 transmission year. We developed a disease forecast to guide public health alerts and messages by pinpointing when and where disease risk is expected to be highest. Such targeted messaging can raise awareness about disease risk, leading to earlier diagnosis and more effective disease management (8).

We adapted our previously published ensemble prediction model relating monthly reported cases per census tract to climatologic or environmental predictors (Appendix Table 1) (3). Using a progressive time-series cross validation approach (Appendix Figure 1), we examined how each of 5 candidate algorithms performed when forecasting future out-of-sample cases and calculated an ensemble weight for each candidate model as proportional to the inverse of each model’s mean out-of-sample prediction error (Appendix Table 2) (9). We fit separate models for each county (for highly endemic regions) or region (for low to moderately endemic regions) to account for spatial differences in the effects of precipitation and temperature on coccidioidomycosis incidence (Appendix Figure 2). Within random forest models, temperature had high variable importance in forecasting cases in wetter, coastal regions, whereas precipitation had high importance in the drier Central Valley (Appendix Figure 3). Those results align with previous findings and emphasize the role of wet periods for fungal growth and hot, dry periods for spore dispersal (3).

To forecast coccidioidomycosis cases, we applied each model to temperature and precipitation data from January 2023–March 2024 and extrapolated temperature and precipitation data through March 2025 (10). We generated future temperature and precipitation estimates beyond April 2024 (the date of analysis) by extrapolating historical monthly temperature averages in each census tract using a 42-year linear trend (1981–2023) and by setting precipitation to the 50th percentile of the 42-year precipitation distribution (10). Because future climate is unknown, we examined the sensitivity of forecasts to 2 alternative precipitation scenarios, drier-than-average (20th percentile) and wetter-than-average (80th percentile), and 2 temperature scenarios, warmer-than-average (+3°F) and cooler-than-average (−3°F). We fit each model to data from January 1, 2000–December 31, 2022, and created an ensemble forecast of cases for each month during January 1, 2023–March 31, 2025, by taking the weighted average of each model’s forecast. We summed cases across calendar years and the coccidioidomycosis transmission year (2), which spans April 1 of 1 year to March 31 of the next. To quantify uncertainty in our forecasts, we generated 90% prediction intervals (PIs) using a 2-step bootstrapping process (Appendix Figure 4). All analyses were conducted in R v.4.3.2 (The R Project for Statistical Computing, https://www.r-project.org).

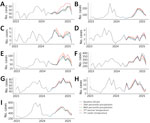

Our ensemble forecast model predicted 11,846 cases (90% PI 11,261–12,505) in California during April 1, 2023–March 31, 2024, closely matching the preliminary state report of 10,519 (Figure 1) (2). The reported number of monthly cases in California in 2023 peaked at 1,462, aligning with our model forecast of 1,619 (90% PI 1,410–1,745). Our forecast model predicted the highest case counts in the Southern San Joaquin Valley, Southern Coast, and Central Coast (Table, Figure 2). Although our model slightly overpredicted cases in these regions, our predictions aligned with the relative magnitude of cases across regions (Appendix Table 3).

Our model forecasted 12,244 cases (90% PI 11,579–12,964) statewide during April 1, 2024–March 31, 2025, a 62% increase over the transmission year 2 years before. The Southern San Joaquin Valley (5,399 [90% PI 4,993–5,902] cases), Southern Coast (3,322 [90% PI 3,172–3,494] cases), and Central Coast (1,207 [90% PI 1,071–1,378] cases) were expected to have the largest number of infections (Table; Figure 2). Our model forecasted pronounced seasonality in disease incidence (Figure 2), with incidence beginning to rise in June and peaking in November at 1,411 (90% PI 1,267–1,587) cases statewide, 98% higher than the 2022 peak (714) and nearly as high as the 2023 peak (1,462). Forecasts were similar under alternative climate scenarios in the forecasted period (Figure 3), suggesting that previous climate conditions are a larger driver of incidence than concurrent climate. Forecasts were robust to model specifications that modeled year as a natural spline and removed collinear predictors (Appendix Table 4).

Predictive models that forecast disease risk can provide public health officials and healthcare providers with information about timing, location, and magnitude of future disease risk (8). Our forecast of high incidence after a swing from extreme drought to heavy precipitation aligns with previous work showing an association between coccidioidomycosis incidence and transitions from anomalously dry to wet years (3). Climate change is altering the hydroclimate of California and adjacent regions, with implications for coccidioidomycosis (11,12). Although changes in average precipitation in California are likely to be modest (13), precipitation variability will likely increase considerably (14), including increasingly large and frequent swings between high and low precipitation conditions from season to season and between years, a phenomenon known as precipitation whiplash (12).

Risk for Coccidioides exposure is likely to be highest in the dry summer and fall months; drier soil leads to more dust and the release of Coccidioides spores. Reported cases typically lag pathogen exposure by 1–2 months, aligning with the observed peak of cases around November (15). However, risk for infection persists year-round. To prevent exposure, persons in regions where coccidioidomycosis is endemic and emerging should avoid dust where possible, practice dust suppression, and consider using N95 masks when disturbing soil. Clinicians should consider coccidioidomycosis when evaluating a patient with respiratory illness who has spent time in an endemic or emerging region, particularly those who are unresponsive to antibiotics, who had exposure to dust or dirt, or whose symptoms last >1–2 weeks.

This analysis is subject to exposure misclassification because case data were aggregated to disease onset, which lags exposure, and census tract of patient residence, which might not represent exposure location. Climate conditions in the forecasted period are uncertain; however, forecasts were similar under the alternate climate scenarios examined. Future work might consider using seasonal climate predictions from large ensemble climate models. Our forecasts cannot account for stochastic point source outbreaks that might lead to anomalously high case counts in certain regions. Continued collaborative work might focus on developing an accurate coccidioidomycosis forecasting system that can be integrated into public health practice in California and other endemic regions.

This article was originally published as a preprint at https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2024.08.30.24312858v1.

Mr. Camponuri is a PhD candidate in environmental health sciences at the University of California, Berkeley, School of Public Health. His research focuses on how environmental change influences the dynamics of coccidioidomycosis in California. Dr. Heaney is an assistant professor at the Herbert Wertheim School of Public Health at the University of California, San Diego. Her research combines epidemiology and computational sciences to understand the relationships between climate variability and human disease.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this manuscript was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) of the National Institutes of Health under award numbers R01AI148336, R01AI176770, and K01AI173529. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views or opinion of the California Department of Public Health or the California Health and Human Services Agency.

References

- Sondermeyer Cooksey GL, Nguyen A, Vugia D, Jain S. Regional analysis of coccidioidomycosis incidence—California, 2000–2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:1817–21. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Nguyen A, Sondermeyer Cooksey G, Djamba Y. Coccidioidomycosis. California provisional monthly report, January–July 2024. Sacramento (California): California Department of Public Health; 2024.

- Head JR, Sondermeyer-Cooksey G, Heaney AK, Yu AT, Jones I, Bhattachan A, et al. Effects of precipitation, heat, and drought on incidence and expansion of coccidioidomycosis in western USA: a longitudinal surveillance study. Lancet Planet Health. 2022;6:e793–803. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Heaney AK, Camponuri SK, Head JR, Collender P, Weaver A, Sondermeyer Cooksey G, et al. Coccidioidomycosis seasonality in California: a longitudinal surveillance study of the climate determinants and spatiotemporal variability of seasonal dynamics, 2000-2021. Lancet Reg Health Am. 2024;38:

100864 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Greene DR, Koenig G, Fisher MC, Taylor JW. Soil isolation and molecular identification of Coccidioides immitis. Mycologia. 2000;92:406–10. DOIGoogle Scholar

- Taylor JW, Barker BM. The endozoan, small-mammal reservoir hypothesis and the life cycle of Coccidioides species. Med Mycol. 2019;57(Supplement_1):S16–20. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- National Centers for Environmental Information, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Climate at a glance [cited 2024 May 15]. https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/access/monitoring/climate-at-a-glance/statewide

- California Department of Public Health. Potential increased risk for Valley fever expected [press release]. August 1, 2023 [cited 2024 Jul 1]. https://www.cdph.ca.gov/Programs/OPA/Pages/NR23-023.aspx

- Bergmeir C, Benítez JM. On the use of cross-validation for time series predictor evaluation. Inf Sci. 2012;191:192–213. DOIGoogle Scholar

- Diffenbaugh NS, Swain DL, Touma D. Anthropogenic warming has increased drought risk in California. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:3931–6. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Swain DL, Langenbrunner B, Neelin JD, Hall A. Increasing precipitation volatility in twenty-first-century California. Nat Clim Chang. 2018;8:427–33. DOIGoogle Scholar

- Persad GG, Swain DL, Kouba C, Ortiz-Partida JP. Inter-model agreement on projected shifts in California hydroclimate characteristics critical to water management. Clim Change. 2020;162:1493–513. DOIGoogle Scholar

- Wood RR, Lehner F, Pendergrass AG, Schlunegger S. Changes in precipitation variability across time scales in multiple global climate model large ensembles. Environ Res Lett. 2021;16:

084022 . DOIGoogle Scholar - Benedict K, Ireland M, Weinberg MP, Gruninger RJ, Weigand J, Chen L, et al. Enhanced surveillance for coccidioidomycosis, 14 US States, 2016. Emerg Infect Dis. 2018;24:1444–52. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

Figures

Table

Cite This ArticleOriginal Publication Date: March 18, 2025

1These authors contributed equally to this article.

Table of Contents – Volume 31, Number 5—May 2025

| EID Search Options |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Please use the form below to submit correspondence to the authors or contact them at the following address:

Jennifer R. Head, Department of Epidemiology, School of Public Health, University of Michigan, 1415 Washington Heights, Ann Arbor, MI 48109-2029, USA

Top