Volume 26, Number 3—March 2020

Research

Stable and Local Reservoirs of Mycobacterium ulcerans Inferred from the Nonrandom Distribution of Bacterial Genotypes, Benin

Figure 3

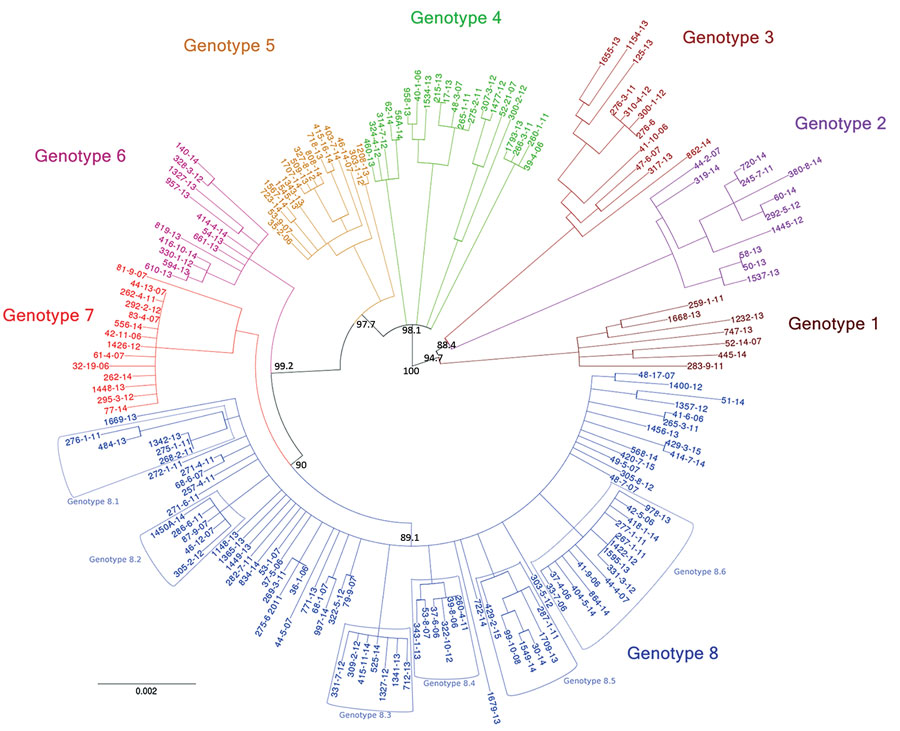

Figure 3. Eight genotypes emerging from phylogenetic analysis of Mycobacterium ulcerans isolates from Buruli ulcer patients in Benin and Nigeria. This rooted circular phylogenetic tree was built by using PhyML (22) on the basis of the core alignment of all single-nucleotide polymorphisms obtained with Snippy 3.2 (19). The bootstrap values are only represented on primitive branches. Branches with bootstrap values <70% were collapsed as polytomies. The outgroup (Papua New Guinea genomes) and the reference genome (Agy99) are not represented (see Appendix 1 Figure 1). On the basis of the segregation indicated by this tree, the genomes were divided in 8 genotypes, which are either monophyletic or paraphyletic. Each taxon was assigned a specific color. Subgenotypes of genotype 8 also are indicated. Scale bar indicates the Nei genetic distance.

References

- Sizaire V, Nackers F, Comte E, Portaels F. Mycobacterium ulcerans infection: control, diagnosis, and treatment. Lancet Infect Dis. 2006;6:288–96. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Asiedu K, Etuaful S. Socioeconomic implications of Buruli ulcer in Ghana: a three-year review. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1998;59:1015–22. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Aiga H, Amano T, Cairncross S, Adomako J, Nanas OK, Coleman S. Assessing water-related risk factors for Buruli ulcer: a case-control study in Ghana. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2004;71:387–92. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Merritt RW, Walker ED, Small PL, Wallace JR, Johnson PD, Benbow ME, et al. Ecology and transmission of Buruli ulcer disease: a systematic review. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2010;4:

e911 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Wallace JR, Mangas KM, Porter JL, Marcsisin R, Pidot SJ, Howden B, et al. Mycobacterium ulcerans low infectious dose and mechanical transmission support insect bites and puncturing injuries in the spread of Buruli ulcer. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017;11:

e0005553 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Williamson HR, Mosi L, Donnell R, Aqqad M, Merritt RW, Small PL. Mycobacterium ulcerans fails to infect through skin abrasions in a guinea pig infection model: implications for transmission. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8:

e2770 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Johnson PD, Azuolas J, Lavender CJ, Wishart E, Stinear TP, Hayman JA, et al. Mycobacterium ulcerans in mosquitoes captured during outbreak of Buruli ulcer, southeastern Australia. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13:1653–60. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Marsollier L, Robert R, Aubry J, Saint André JP, Kouakou H, Legras P, et al. Aquatic insects as a vector for Mycobacterium ulcerans. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2002;68:4623–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Portaels F, Elsen P, Guimaraes-Peres A, Fonteyne PA, Meyers WM. Insects in the transmission of Mycobacterium ulcerans infection. Lancet. 1999;353:986. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- van der Werf TS, Stinear T, Stienstra Y, van der Graaf WT, Small PL. Mycolactones and Mycobacterium ulcerans disease. Lancet. 2003;362:1062–4. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Buultjens AH, Vandelannoote K, Meehan CJ, Eddyani M, de Jong BC, Fyfe JAM, et al. Comparative genomics shows that Mycobacterium ulcerans migration and expansion preceded the rise of Buruli ulcer in southeastern Australia. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2018;84:e02612–7. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Vandelannoote K, Phanzu DM, Kibadi K, Eddyani M, Meehan CJ, Jordaens K, et al. Mycobacterium ulcerans population genomics to inform on the spread of Buruli ulcer across central Africa. MSphere. 2019;4:e00472–18. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Wu J, Tschakert P, Klutse E, Ferring D, Ricciardi V, Hausermann H, et al. Buruli ulcer disease and its association with land cover in southwestern Ghana. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9:

e0003840 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Bolz M, Bratschi MW, Kerber S, Minyem JC, Um Boock A, Vogel M, et al. Locally confined clonal complexes of Mycobacterium ulcerans in two Buruli ulcer endemic regions of Cameroon. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9:

e0003802 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Vandelannoote K, Meehan CJ, Eddyani M, Affolabi D, Phanzu DM, Eyangoh S, et al. Multiple introductions and recent spread of the emerging human pathogen Mycobacterium ulcerans across Africa. Genome Biol Evol. 2017;9:414–26. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Kambarev S, Corvec S, Chauty A, Marion E, Marsollier L, Pecorari F. Draft genome sequence of Mycobacterium ulcerans S4018 isolated from a patient with an active Buruli ulcer in Benin, Africa. Genome Announc. 2017;5:e00248–17. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Andrew S. FastQC: a quality control tool for high throughput sequence data. 2010 [cited 2019 Apr 1].

- Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2114–20. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Seemann T. Snippy: fast bacterial variant calling from NGS reads. 2015 [cited 2019 Apr 1].

- Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1754–60. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Stinear TP, Seemann T, Pidot S, Frigui W, Reysset G, Garnier T, et al. Reductive evolution and niche adaptation inferred from the genome of Mycobacterium ulcerans, the causative agent of Buruli ulcer. Genome Res. 2007;17:192–200. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Guindon S, Dufayard JF, Lefort V, Anisimova M, Hordijk W, Gascuel O. New algorithms and methods to estimate maximum-likelihood phylogenies: assessing the performance of PhyML 3.0. Syst Biol. 2010;59:307–21. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Hodcroft E. TreeCollapserCL. 2012 [cited 2019 Apr 1].

- Kulldorff M. SatScan: software for the spatial and space-time scan statistics. 2019 [cited 2019 Apr 1].

- Team QGIS Development. QGIS Geographic Information System. Project OSGF. 2019 [cited 2019 Apr 1].

- R Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Computing RFfS. 2019 [cited 2019 Apr 1].

- Powers DMW. Evaluation: from precision, recall and F-Measure to ROC, informedness, markedness, and correlation. J Mach Learn Technol. 2011;2:37–63.

- Bennett SD, Lowther SA, Chingoli F, Chilima B, Kabuluzi S, Ayers TL, et al. Assessment of water, sanitation and hygiene interventions in response to an outbreak of typhoid fever in Neno District, Malawi. PLoS One. 2018;13:

e0193348 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Davies HG, Bowman C, Luby SP. Cholera - management and prevention. J Infect. 2017;74(Suppl 1):S66–73. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Mitjà O, Marks M, Bertran L, Kollie K, Argaw D, Fahal AH, et al. Integrated control and management of neglected tropical skin diseases. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017;11:

e0005136 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Brou T, Broutin H, Elguero E, Asse H, Guegan JF. Landscape diversity related to Buruli ulcer disease in Côte d’Ivoire. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2008;2:

e271 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Landier J, Gaudart J, Carolan K, Lo Seen D, Guégan JF, Eyangoh S, et al. Spatio-temporal patterns and landscape-associated risk of Buruli ulcer in Akonolinga, Cameroon. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8:

e3123 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Marion E, Landier J, Boisier P, Marsollier L, Fontanet A, Le Gall P, et al. Geographic expansion of Buruli ulcer disease, Cameroon. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17:551–3. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Nackers F, Johnson RC, Glynn JR, Zinsou C, Tonglet R, Portaels F. Environmental and health-related risk factors for Mycobacterium ulcerans disease (Buruli ulcer) in Benin. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007;77:834–6. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Pouillot R, Matias G, Wondje CM, Portaels F, Valin N, Ngos F, et al. Risk factors for buruli ulcer: a case control study in Cameroon. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2007;1:

e101 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Raghunathan PL, Whitney EA, Asamoa K, Stienstra Y, Taylor TH Jr, Amofah GK, et al. Risk factors for Buruli ulcer disease (Mycobacterium ulcerans Infection): results from a case-control study in Ghana. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40:1445–53. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Wagner T, Benbow ME, Burns M, Johnson RC, Merritt RW, Qi J, et al. A Landscape-based model for predicting Mycobacterium ulcerans infection (Buruli Ulcer disease) presence in Benin, West Africa. EcoHealth. 2008;5:69–79. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Röltgen K, Stinear TP, Pluschke G. The genome, evolution and diversity of Mycobacterium ulcerans. Infect Genet Evol. 2012;12:522–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Demangel C, Stinear TP, Cole ST. Buruli ulcer: reductive evolution enhances pathogenicity of Mycobacterium ulcerans. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2009;7:50–60. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Rondini S, Käser M, Stinear T, Tessier M, Mangold C, Dernick G, et al. Ongoing genome reduction in Mycobacterium ulcerans. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13:1008–15. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Yerramilli A, Tay EL, Stewardson AJ, Fyfe J, O’Brien DP, Johnson PDR. The association of rainfall and Buruli ulcer in southeastern Australia. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2018;12:

e0006757 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Tanser FC, Le Sueur D. The application of geographical information systems to important public health problems in Africa. Int J Health Geogr. 2002;1:4. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Carpi G, Walter KS, Bent SJ, Hoen AG, Diuk-Wasser M, Caccone A. Whole genome capture of vector-borne pathogens from mixed DNA samples: a case study of Borrelia burgdorferi. BMC Genomics. 2015;16:434. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar