Volume 26, Number 3—March 2020

Research

Stable and Local Reservoirs of Mycobacterium ulcerans Inferred from the Nonrandom Distribution of Bacterial Genotypes, Benin

Figure 7

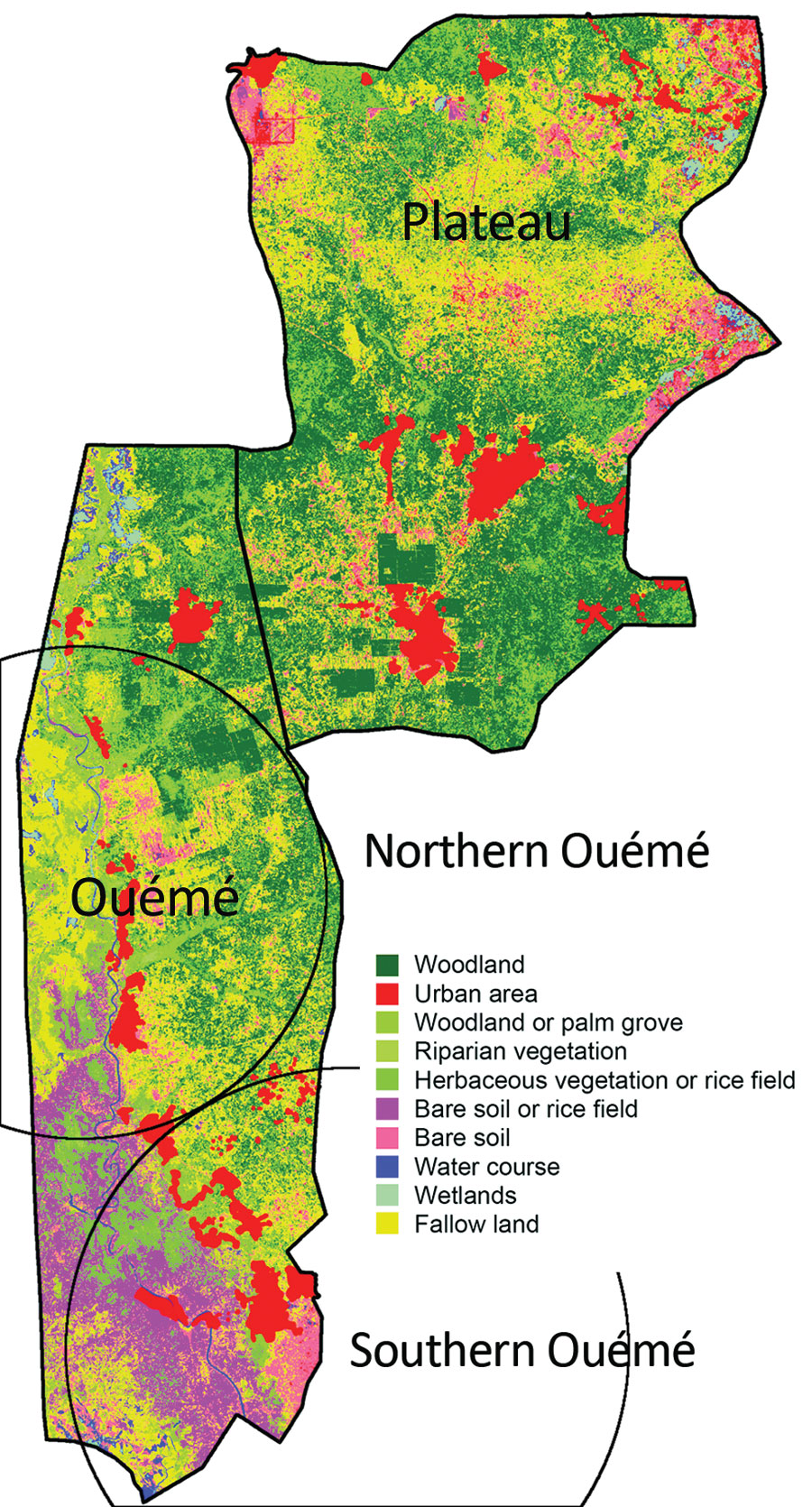

Figure 7. Land use and land cover assessment from Sentinel-2 imaging of Benin. The Ouémé region has specific land and plant formations, such as grassy savanna, grasslands, and swamps. Soils easily become saturated with water because of a shallow water table and the proximity of a river, which causes floods and a natural delta formation in the south of the region. Circles indicate the detected northern and southern Ouémé Mycobacterium ulcerans clusters.

Page created: February 20, 2020

Page updated: February 20, 2020

Page reviewed: February 20, 2020

The conclusions, findings, and opinions expressed by authors contributing to this journal do not necessarily reflect the official position of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the Public Health Service, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or the authors' affiliated institutions. Use of trade names is for identification only and does not imply endorsement by any of the groups named above.