Volume 30, Number 8—August 2024

Research

SARS-CoV-2 Seropositivity in Urban Population of Wild Fallow Deer, Dublin, Ireland, 2020–2022

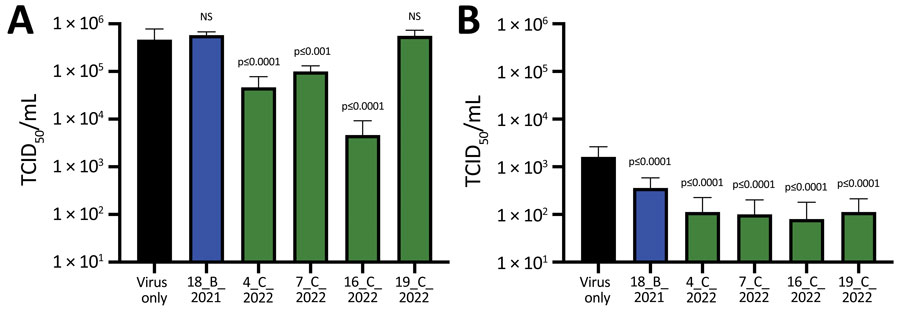

Figure 3

Figure 3. Infectivity of SARS-CoV-2 infectious viruses after incubation with SARS-CoV-2–positive serum samples from wild fallow deer, Dublin, Ireland, 2020–2022. Deer serum samples were incubated with infectious SARS-CoV-2 ancestral strain Italy_INMI1 (A) or Omicron BA.1 (B) and then used to infect Vero E6/TMPRSS2 cells. Identification numbers of deer are indicated. Cytopathic effect was calculated as TCID50, as previously described (19). Data are from 2 independent experiments with 8 biologic replicates per experiment. p values were calculated by using 1-way analysis of variance (Appendix 2 Tables 2, 3). Error bars indicate SDs. NS, not significant; TCID50, 50% tissue culture infectious dose.

References

- V’kovski P, Kratzel A, Steiner S, Stalder H, Thiel V. Coronavirus biology and replication: implications for SARS-CoV-2. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2021;19:155–70. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. SARS-CoV-2 in animals: susceptibility of animal species, risk for animal and public health, monitoring, prevention and control. February 28, 2023 [cited 2023 Jul 21]. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/sars-cov-2-animals-susceptibility-animal-species-risk-animal-and-public-health

- Chandler JC, Bevins SN, Ellis JW, Linder TJ, Tell RM, Jenkins-Moore M, et al. SARS-CoV-2 exposure in wild white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus). Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021;118:

e2114828118 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Hale VL, Dennis PM, McBride DS, Nolting JM, Madden C, Huey D, et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection in free-ranging white-tailed deer. Nature. 2022;602:481–6. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Martins M, Boggiatto PM, Buckley A, Cassmann ED, Falkenberg S, Caserta LC, et al. From Deer-to-Deer: SARS-CoV-2 is efficiently transmitted and presents broad tissue tropism and replication sites in white-tailed deer. PLoS Pathog. 2022;18:

e1010197 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Palmer MV, Martins M, Falkenberg S, Buckley A, Caserta LC, Mitchell PK, et al. Susceptibility of white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) to SARS-CoV-2. J Virol. 2021;95:e00083–21. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- World Organisation for Animal Health. OIE statement on monitoring white-tailed deer for SARS-CoV-2. December 3, 2021 [cited 2023 Jul 21]. https://www.woah.org/en/oie-statement-on-monitoring-white-tailed-deer-for-sars-cov-2

- Holding M, Otter AD, Dowall S, Takumi K, Hicks B, Coleman T, et al. Screening of wild deer populations for exposure to SARS-CoV-2 in the United Kingdom, 2020-2021. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2022;69:e3244–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Moreira-Soto A, Walzer C, Czirják GÁ, Richter MH, Marino SF, Posautz A, et al. Serological evidence that SARS-CoV-2 has not emerged in deer in Germany or Austria during the COVID-19 pandemic. Microorganisms. 2022;10:748. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Lean FZX, Cox R, Madslien K, Spiro S, Nymo IH, Bröjer C, et al. Tissue distribution of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor in wild animals with a focus on artiodactyls, mustelids and phocids. One Health. 2023;16:

100492 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Zhang Y, Wei M, Wu Y, Wang J, Hong Y, Huang Y, et al. Cross-species tropism and antigenic landscapes of circulating SARS-CoV-2 variants. Cell Rep. 2022;38:

110558 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Griffin LL, Haigh A, Amin B, Faull J, Norman A, Ciuti S. Artificial selection in human-wildlife feeding interactions. J Anim Ecol. 2022;91:1892–905. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Amin B, Jennings DJ, Smith AF, Quinn M, Chari S, Haigh A, et al. In utero accumulated steroids predict neonate anti-predator response in a wild mammal. Funct Ecol. 2021;35:1255–67. DOIGoogle Scholar

- Griffin LL, Haigh A, Conteddu K, Andaloc M, McDonnell P, Ciuti S. Reducing risky interactions: identifying barriers to the successful management of human–wildlife conflict in an urban parkland. People Nat. 2022;4:918–30. DOIGoogle Scholar

- Grierson SS, McGowan S, Cook C, Steinbach F, Choudhury B. Molecular and in vitro characterisation of hepatitis E virus from UK pigs. Virology. 2019;527:116–21. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Purves K, Haverty R, O’Neill T, Folan D, O’Reilly S, Baird AW, et al. A novel antiviral formulation containing caprylic acid inhibits SARS-CoV-2 infection of a human bronchial epithelial cell model. J Gen Virol. 2023;104:

001821 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Fletcher NF, Meredith LW, Tidswell EL, Bryden SR, Gonçalves-Carneiro D, Chaudhry Y, et al. A novel antiviral formulation inhibits a range of enveloped viruses. J Gen Virol. 2020;101:1090–102. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Reed LJ, Muench H. A simple method of estimating fifty percent endpoints. Am J Hyg. 1938;27:493–7.

- Matsuyama S, Nao N, Shirato K, Kawase M, Saito S, Takayama I, et al. Enhanced isolation of SARS-CoV-2 by TMPRSS2-expressing cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117:7001–3. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Reynolds LJ, Gonzalez G, Sala-Comorera L, Martin NA, Byrne A, Fennema S, et al. SARS-CoV-2 variant trends in Ireland: Wastewater-based epidemiology and clinical surveillance. Sci Total Environ. 2022;838:

155828 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Katoh K, Rozewicki J, Yamada KD. MAFFT online service: multiple sequence alignment, interactive sequence choice and visualization. Brief Bioinform. 2019;20:1160–6. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- World Health Organization. Joint statement on the prioritization of monitoring SARS-CoV-2 infection in wildlife and preventing the formation of animal reservoirs. March 7, 2022 [cited 2023 Jul 21]. https://www.who.int/news/item/07-03-2022-joint-statement-on-the-prioritization-of-monitoring-sars-cov-2-infection-in-wildlife-and-preventing-the-formation-of-animal-reservoirs

- World Organisation for Animal Health. SARS-COV-2 in animals—situation report 11. March 31, 2022 [cited 2023 Jul 21]. https://www.woah.org/app/uploads/2022/04/sars-cov-2-situation-report-11.pdf

- Pickering B, Lung O, Maguire F, Kruczkiewicz P, Kotwa JD, Buchanan T, et al. Divergent SARS-CoV-2 variant emerges in white-tailed deer with deer-to-human transmission. Nat Microbiol. 2022;7:2011–24. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Pitra C, Fickel J, Meijaard E, Groves PC. Evolution and phylogeny of old world deer. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2004;33:880–95. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Griffin LL, Nolan G, Haigh A, Condon H, O’Hagan H, McDonnell P, et al. How can we tackle interruptions to human–wildlife feeding management? Adding media campaigns to the wildlife manager’s toolbox. People Nat. 2023;5:1299–315. DOIGoogle Scholar

- Embregts CWE, Verstrepen B, Langermans JAM, Böszörményi KP, Sikkema RS, de Vries RD, et al. Evaluation of a multi-species SARS-CoV-2 surrogate virus neutralization test. One Health. 2021;13:

100313 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Tan CW, Chia WN, Zhu F, Young BE, Chantasrisawad N, Hwa SH, et al. SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant emerged under immune selection. Nat Microbiol. 2022;7:1756–61. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Dastjerdi A, Floyd T, Swinson V, Davies H, Barber A, Wight A. Parainfluenza and corona viruses in a fallow deer (Dama dama) with fatal respiratory disease. Front Vet Sci. 2022;9:

1059681 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Graham DA, Gallagher C, Carden RF, Lozano JM, Moriarty J, O’Neill R. A survey of free-ranging deer in Ireland for serological evidence of exposure to bovine viral diarrhoea virus, bovine herpes virus-1, bluetongue virus and Schmallenberg virus. Ir Vet J. 2017;70:13. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Biro PA, Dingemanse NJ. Sampling bias resulting from animal personality. Trends Ecol Evol. 2009;24:66–7. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Bagato O, Balkema-Buschmann A, Todt D, Weber S, Gömer A, Qu B, et al. Spatiotemporal analysis of SARS-CoV-2 infection reveals an expansive wave of monocyte-derived macrophages associated with vascular damage and virus clearance in hamster lungs. Microbiol Spectr. 2024;12:

e0246923 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Lean FZX, Lamers MM, Smith SP, Shipley R, Schipper D, Temperton N, et al. Development of immunohistochemistry and in situ hybridisation for the detection of SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded specimens. Sci Rep. 2020;10:21894. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Hamer SA, Nunez C, Roundy CM, Tang W, Thomas L, Richison J, et al. Persistence of SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibodies longer than 13 months in naturally infected, captive white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus), Texas. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2022;11:2112–5. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Lopes LR. Cervids ACE2 residues that bind the spike protein can provide susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2. EcoHealth. 2023;20:9–17. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

1These authors contributed equally to this article.