Volume 30, Number 9—September 2024

Research

Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification Assay to Detect Invasive Malaria Vector Anopheles stephensi Mosquitoes

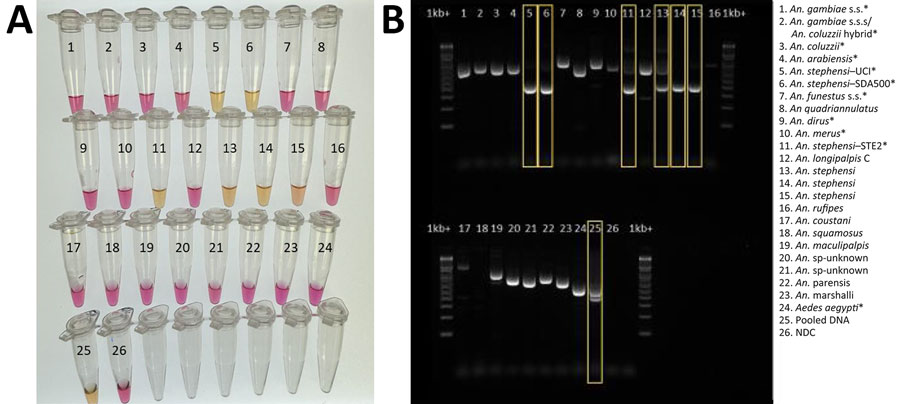

Figure 4

Figure 4. Validation of colorimetric loop-mediated isothermal amplification assay to detect invasive malaria vector Anopheles stephensi mosquitoes. A) Results using new assay. B) Results using existing An. stephensi PCR (13); yellow boxes indicate An. stephensi products. Conventional PCR resulted in difficult-to-interpret gel bands for An. longipalpis C, Aedes aegypti, and An. coustani samples, similar to An. stephensi samples, and inconsistently produced double bands (positive detection) on sequence-confirmed An. stephensi samples from Kenya. Asterisks (*) in key indicate samples from insectary-reared mosquitoes. Samples 12–23 came from sequence-confirmed field-collected specimens. Sample 25 contained a pool of assorted mosquito DNA species, in which An. stephensi was represented 1:10. For both assays, 1 µL extracted DNA was used. NDC, no DNA template control; UCI, An. stephensi laboratory colony (BEI Resources, https://www.beiresources.org).

References

- Faulde MK, Rueda LM, Khaireh BA. First record of the Asian malaria vector Anopheles stephensi and its possible role in the resurgence of malaria in Djibouti, Horn of Africa. Acta Trop. 2014;139:39–43. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- World Health Organization. WHO initiative to stop the spread of Anopheles stephensi in Africa. 2023 update [cited 2023 Aug 15]. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-UCN-GMP-2022.06

- World Health Organization. Vector alert: Anopheles stephensi invasion and spread: Horn of Africa, the Republic of the Sudan and surrounding geographical areas, and Sri Lanka: information note. 2019 [cited 2019 Sep 1]. https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/326595

- Emiru T, Getachew D, Murphy M, Sedda L, Ejigu LA, Bulto MG, et al. Evidence for a role of Anopheles stephensi in the spread of drug- and diagnosis-resistant malaria in Africa. Nat Med. 2023;29:3203–11. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Faulde MK, Pages F, Uedelhoven W. Bioactivity and laundering resistance of five commercially available, factory-treated permethrin-impregnated fabrics for the prevention of mosquito-borne diseases: the need for a standardized testing and licensing procedure. Parasitol Res. 2016;115:1573–82. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Balkew M, Mumba P, Yohannes G, Abiy E, Getachew D, Yared S, et al. An update on the distribution, bionomics, and insecticide susceptibility of Anopheles stephensi in Ethiopia, 2018-2020. Malar J. 2021;20:263. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Sinka ME, Pironon S, Massey NC, Longbottom J, Hemingway J, Moyes CL, et al. A new malaria vector in Africa: Predicting the expansion range of Anopheles stephensi and identifying the urban populations at risk. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117:24900–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Hamlet A, Dengela D, Tongren JE, Tadesse FG, Bousema T, Sinka M, et al. The potential impact of Anopheles stephensi establishment on the transmission of Plasmodium falciparum in Ethiopia and prospective control measures. BMC Med. 2022;20:135. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- World Health Organization. Vector alert: Anopheles stephensi invasion and spread in Africa and Sri Lanka. 2022 [cited 2022 Oct 15]. https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/365710

- US President’s Malaria Initiative. Responding to Anopheles stephensi [cited 2023 Feb 22]. https://www.pmi.gov/what-we-do/entomological-monitoring/anstephensi

- Coetzee M. Key to the females of Afrotropical Anopheles mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae). Malar J. 2020;19:70. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Ahmed A, Irish SR, Zohdy S, Yoshimizu M, Tadesse FG. Strategies for conducting Anopheles stephensi surveys in non-endemic areas. Acta Trop. 2022;236:

106671 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Singh OP, Kaur T, Sharma G, Kona MP, Mishra S, Kapoor N, et al. Molecular tools for early detection of invasive malaria vector Anopheles stephensi mosquitoes. Emerg Infect Dis. 2023;29:36–44. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Garg N, Ahmad FJ, Kar S. Recent advances in loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) for rapid and efficient detection of pathogens. Curr Res Microb Sci. 2022;3:

100120 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Hatano B, Maki T, Obara T, Fukumoto H, Hagisawa K, Matsushita Y, et al. LAMP using a disposable pocket warmer for anthrax detection, a highly mobile and reliable method for anti-bioterrorism. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2010;63:36–40. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Dao Thi VL, Herbst K, Boerner K, Meurer M, Kremer LP, Kirrmaier D, et al. A colorimetric RT-LAMP assay and LAMP-sequencing for detecting SARS-CoV-2 RNA in clinical samples. Sci Transl Med. 2020;12:

eabc7075 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - New England Biolabs. NEB LAMP primer design tool version 1.4.1 [cited 2023 May 1]. https://www.neb.com/en-us/neb-primer-design-tools/neb-primer-design-tools

- Mishra S, Sharma G, Das MK, Pande V, Singh OP. Intragenomic sequence variations in the second internal transcribed spacer (ITS2) ribosomal DNA of the malaria vector Anopheles stephensi. PLoS One. 2021;16:

e0253173 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Notomi T, Okayama H, Masubuchi H, Yonekawa T, Watanabe K, Amino N, et al. Loop-mediated isothermal amplification of DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:

E63 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Nagamine K, Hase T, Notomi T. Accelerated reaction by loop-mediated isothermal amplification using loop primers. Mol Cell Probes. 2002;16:223–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Bonizzoni M, Afrane Y, Yan G. Loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) for rapid identification of Anopheles gambiae and Anopheles arabiensis mosquitoes. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2009;81:1030–4. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- BEI Resources Malaria Research and Reference Reagent Resource Center (MR4) [cited 2023 Jun 15]. https://www.beiresources.org/About/MR4Home.aspx

- Ochomo EO, Milanoi S, Abong’o B, Onyango B, Muchoki M, Omoke D, et al. Detection of Anopheles stephensi mosquitoes by molecular surveillance, Kenya. Emerg Infect Dis. 2023;29:2498–508. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Folmer O, Black M, Hoeh W, Lutz R, Vrijenhoek R. DNA primers for amplification of mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I from diverse metazoan invertebrates. Mol Mar Biol Biotechnol. 1994;3:294–9.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Gillies MT, Coetzee M. A supplement to the Anophelinae of Africa South of the Sahara. Publ South African Institute for Medical Research Journal. 1987;55:1–143.

- World Health Organization. Malaria threats map [cited 2023 Aug 7]. https://apps.who.int/malaria/maps/threats

- Sherrard-Smith E, Skarp JE, Beale AD, Fornadel C, Norris LC, Moore SJ, et al. Mosquito feeding behavior and how it influences residual malaria transmission across Africa. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019;116:15086–95. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Scott JA, Brogdon WG, Collins FH. Identification of single specimens of the Anopheles gambiae complex by the polymerase chain reaction. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1993;49:520–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Carter TE, Yared S, Gebresilassie A, Bonnell V, Damodaran L, Lopez K, et al. First detection of Anopheles stephensi Liston, 1901 (Diptera: culicidae) in Ethiopia using molecular and morphological approaches. Acta Trop. 2018;188:180–6. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Chitnis N, Smith T, Steketee R. A mathematical model for the dynamics of malaria in mosquitoes feeding on a heterogeneous host population. J Biol Dyn. 2008;2:259–85. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Yakob L, Yan G. Modeling the effects of integrating larval habitat source reduction and insecticide treated nets for malaria control. PLoS One. 2009;4:

e6921 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Dye C. The analysis of parasite transmission by bloodsucking insects. Annu Rev Entomol. 1992;37:1–19. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar