Volume 31, Number 4—April 2025

Research

Detection and Decontamination of Chronic Wasting Disease Prions during Venison Processing

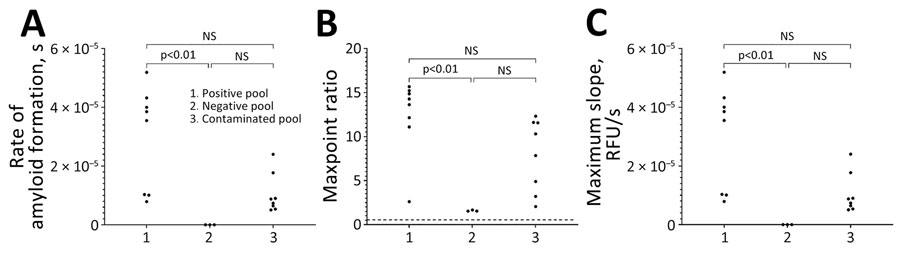

Figure 4

Figure 4. Results of real-time quaking-induced conversion in study of detection and decontamination of chronic wasting disease prions during venison processing. Results are shown for the CWD-positive muscle homogenate (positive pool), CWD-negative muscle homogenate before passing through a contaminated grinder (negative pool), and the CWD-negative muscle homogenate after passing through a contaminated meat grinder (contaminated pool). A) Rate of amyloid formation; B) maxpoint ratio (ratio of the maximum value to the initial reading) (28); C) maximum slope. NS, not statistically significant.

References

- Prusiner SB. Novel proteinaceous infectious particles cause scrapie. Science. 1982;216:136–44. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Miller MW, Williams ES. Chronic wasting disease of cervids. In: Harris DA, editor. Mad cow disease and related spongiform encephalopathies. Berlin: Springer; 2004. p. 193–214.

- Williams ES, Young S. Chronic wasting disease of captive mule deer: a spongiform encephalopathy. J Wildl Dis. 1980;16:89–98. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- US Geological Survey. Distribution of chronic wasting disease in North America [cited 2024 May 22]. https://www.usgs.gov/media/images/distribution-chronic-wasting-disease-north-america-0

- National Deer Association. NDA’s deer report 2023 [cited 2024 Aug 7]. https://deerassociation.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/NDA-DR2023-FINAL.pdf

- Manitoba Wildlife Federation. The challenge of CWD: insidious, dire and urgent, late-breaking research reinforces the need for action [cited 2024 May 22]. https://mwf.mb.ca/archives/709

- Li M, Schwabenlander MD, Rowden GR, Schefers JM, Jennelle CS, Carstensen M, et al. RT-QuIC detection of CWD prion seeding activity in white-tailed deer muscle tissues. Sci Rep. 2021;11:16759. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. About chronic wasting disease (CWD) [cited 2024 May 22]. https://www.cdc.gov/chronic-wasting/about/index.html

- Tranulis MA, Tryland M. The zoonotic potential of chronic wasting disease—a review. Foods. 2023;12:824. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Otero A, Duque Velasquez C, McKenzie D, Aiken J. Emergence of CWD strains. Cell Tissue Res. 2023;392:135–48. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Cassmann ED, Frese AJ, Moore SJ, Greenlee JJ. Transmission of raccoon-passaged chronic wasting disease agent to white-tailed deer. Viruses. 2022;14:1578. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Henderson DM, Davenport KA, Haley NJ, Denkers ND, Mathiason CK, Hoover EA. Quantitative assessment of prion infectivity in tissues and body fluids by real-time quaking-induced conversion. J Gen Virol. 2015;96:210–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Tennant JM, Li M, Henderson DM, Tyer ML, Denkers ND, Haley NJ, et al. Shedding and stability of CWD prion seeding activity in cervid feces. PLoS One. 2020;15:

e0227094 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Miller MW, Williams ES, Hobbs NT, Wolfe LL. Environmental sources of prion transmission in mule deer. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10:1003–6. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Escobar LE, Pritzkow S, Winter SN, Grear DA, Kirchgessner MS, Dominguez-Villegas E, et al. The ecology of chronic wasting disease in wildlife. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc. 2020;95:393–408. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Orrú CD, Groveman BR, Hughson AG, Barrio T, Isiofia K, Race B, et al. Sensitive detection of pathological seeds of α-synuclein, tau and prion protein on solid surfaces. PLoS Pathog. 2024;20:

e1012175 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Georgsson G, Sigurdarson S, Brown P. Infectious agent of sheep scrapie may persist in the environment for at least 16 years. J Gen Virol. 2006;87:3737–40. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Yuan Q, Rowden G, Wolf TM, Schwabenlander MD, Larsen PA, Bartelt-Hunt SL, et al. Sensitive detection of chronic wasting disease prions recovered from environmentally relevant surfaces. Environ Int. 2022;166:

107347 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Soto P, Bravo-Risi F, Benavente R, Lichtenberg S, Lockwood M, Reed JH, et al. Identification of chronic wasting disease prions in decaying tongue tissues from exhumed white-tailed deer. MSphere. 2023;8:

e0027223 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Chesney AR, Booth CJ, Lietz CB, Li L, Pedersen JA. Peroxymonosulfate rapidly inactivates the disease-associated prion protein. Environ Sci Technol. 2016;50:7095–105. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Williams K, Hughson AG, Chesebro B, Race B. Inactivation of chronic wasting disease prions using sodium hypochlorite. PLoS One. 2019;14:

e0223659 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Hughson AG, Race B, Kraus A, Sangaré LR, Robins L, Groveman BR, et al. Inactivation of prions and amyloid seeds with hypochlorous acid. PLoS Pathog. 2016;12:

e1005914 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Gavin C, Henderson D, Benestad SL, Simmons M, Adkin A. Estimating the amount of Chronic Wasting Disease infectivity passing through abattoirs and field slaughter. Prev Vet Med. 2019;166:28–38. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Nastasijevic I, Boskovic M, Glisic M. Abattoir hygiene. In: Knowles ME, Anelich LE, Boobis AR, Popping B, editors. Present knowledge in food safety: a risk-based approach through the food chain. San Diego: Academic Press; 2023. p. 412–38.

- Atarashi R, Sano K, Satoh K, Nishida N. Real-time quaking-induced conversion: a highly sensitive assay for prion detection. Prion. 2011;5:150–3. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Haley NJ, Van de Motter A, Carver S, Henderson D, Davenport K, Seelig DM, et al. Prion-seeding activity in cerebrospinal fluid of deer with chronic wasting disease. PLoS One. 2013;8:

e81488 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Gallups NJ, Harms AS. ‘Seeding’ the idea of early diagnostics in synucleinopathies. Brain. 2022;145:418–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Rowden GR, Picasso-Risso C, Li M, Schwabenlander MD, Wolf TM, Larsen PA. Standardization of data analysis for RT-QuIC-based detection of chronic wasting disease. Pathogens. 2023;12:309. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Wilham JM, Orrú CD, Bessen RA, Atarashi R, Sano K, Race B, et al. Rapid end-point quantitation of prion seeding activity with sensitivity comparable to bioassays. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:

e1001217 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Cooke CM, Rodger J, Smith A, Fernie K, Shaw G, Somerville RA. Fate of prions in soil: detergent extraction of PrP from soils. Environ Sci Technol. 2007;41:811–7. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Pitardi D, Meloni D, Maurella C, Di Vietro D, Nocilla L, Piscopo A, et al. Specified risk material removal practices: can we reduce the BSE hazard to human health? Food Control. 2013;30:668–74. DOIGoogle Scholar

Page created: February 07, 2025

Page updated: March 24, 2025

Page reviewed: March 24, 2025

The conclusions, findings, and opinions expressed by authors contributing to this journal do not necessarily reflect the official position of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the Public Health Service, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or the authors' affiliated institutions. Use of trade names is for identification only and does not imply endorsement by any of the groups named above.