Volume 27, Number 3—March 2021

Research

Foodborne Origin and Local and Global Spread of Staphylococcus saprophyticus Causing Human Urinary Tract Infections

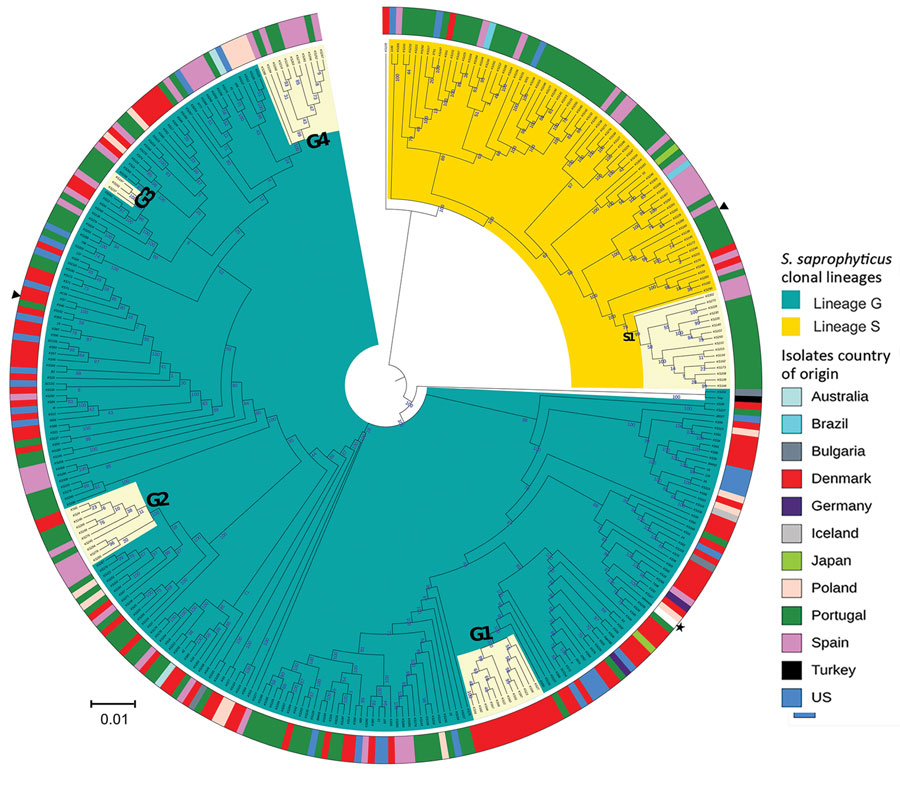

Figure 1

Figure 1. Maximum-likelihood tree of Staphylococcus saprophyticus isolates recovered from human infections and colonization globally, 1997–2017. The tree was constructed by using 9,134 SNPs without recombination. Among analyzed isolates, 321 were recovered from UTIs, 12 from blood, and 4 from colonization. Each node represents a strain; nodes with identical color belong to the same lineage. The assembled contigs were mapped to the reference genome S. saprophyticus ATCC 15305 (GenBank accession no. AP008934.1; black star). Polymorphic sites resulting from recombination events in the single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) alignments were filtered out by using Gubbins version 2.3.4 (12). Maximum likelihood tree was reconstructed by using RAxML version 8.2.4 (https://github.com/stamatak/standard-RAxML). We performed generalized time-reversible nucleotide substitution model with gamma correction with 100 bootstraps random resampling for support. We visualized the tree by using Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL; https://itol.embl.de). Black triangles represent isolates fully sequenced by using the long-read nanopore technologies and used as reference to estimate r/m in the respective lineage. Cream color represents clusters G1, G2, G3, G4, and S1, which had dissemination and transmission in same country and in different countries. The outer ring represents isolates’ country of origin; blocks with identical color represent isolates from the same country. Of note, cluster G4 contains a pair of isolates collected in 2016 that had only 10 SNPs difference; one is a blood isolate from Barcelona, Spain (KS266) and the other is a UTI isolate recovered in Lisbon, Portugal (KS135). Scale bar indicates number of substitutions per site. UTI, urinary tract infection; r/m, recombination to mutation ratio.

References

- Becker K, Heilmann C, Peters G. Coagulase-negative staphylococci. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2014;27:870–926. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Latham RH, Running K, Stamm WE. Urinary tract infections in young adult women caused by Staphylococcus saprophyticus. JAMA. 1983;250:3063–6. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Garduño E, Márquez I, Beteta A, Said I, Blanco J, Pineda T. Staphylococcus saprophyticus causing native valve endocarditis. Scand J Infect Dis. 2005;37:690–1. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Rupp ME, Soper DE, Archer GL. Colonization of the female genital tract with Staphylococcus saprophyticus. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:2975–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- de Sousa VS, da-Silva APS, Sorenson L, Paschoal RP, Rabello RF, Campana EH, et al. Staphylococcus saprophyticus recovered from humans, food, and recreational waters in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Int J Microbiol. 2017;2017:

4287547 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Hedman P, Ringertz O, Eriksson B, Kvarnfors P, Andersson M, Bengtsson L, et al. Staphylococcus saprophyticus found to be a common contaminant of food. J Infect. 1990;21:11–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Lee B, Jeong D-W, Lee J-H. Genetic diversity and antibiotic resistance of Staphylococcus saprophyticus isolates from fermented foods and clinical samples. J Korean Soc Appl Biol Chem. 2015;58:659–68. DOIGoogle Scholar

- Mortimer TD, Annis DS, O’Neill MB, Bohr LL, Smith TM, Poinar HN, et al. Adaptation in a fibronectin binding autolysin of Staphylococcus saprophyticus. MSphere. 2017;2:e00511–7. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Kuroda M, Yamashita A, Hirakawa H, Kumano M, Morikawa K, Higashide M, et al. Whole genome sequence of Staphylococcus saprophyticus reveals the pathogenesis of uncomplicated urinary tract infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:13272–7 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Hansen KH, Andreasen MR, Pedersen MS, Westh H, Jelsbak L, Schønning K. Resistance to piperacillin/tazobactam in Escherichia coli resulting from extensive IS26-associated gene amplification of blaTEM-1. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2019;74:3179–83. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Kaas RS, Leekitcharoenphon P, Aarestrup FM, Lund O. Solving the problem of comparing whole bacterial genomes across different sequencing platforms. PLoS One. 2014;9:

e104984 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Croucher NJ, Page AJ, Connor TR, Delaney AJ, Keane JA, Bentley SD, et al. Rapid phylogenetic analysis of large samples of recombinant bacterial whole genome sequences using Gubbins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:

e15 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Brynildsrud O, Bohlin J, Scheffer L, Eldholm V. Erratum to: Rapid scoring of genes in microbial pan-genome-wide association studies with Scoary. Genome Biol. 2016;17:262. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Chen L, Zheng D, Liu B, Yang J, Jin Q. VFDB 2016: hierarchical and refined dataset for big data analysis—10 years on. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44(D1):D694–7. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Monk IR, Foster TJ. Genetic manipulation of Staphylococci-breaking through the barrier. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2012;2:49. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Tomita K, Nagura T, Okuhara Y, Nakajima-Adachi H, Shigematsu N, Aritsuka T, et al. Dietary melibiose regulates th cell response and enhances the induction of oral tolerance. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2007;71:2774–80. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Dinicola S, Minini M, Unfer V, Verna R, Cucina A, Bizzarri M. Nutritional and acquired deficiencies in inositol bioavailability. Correlations with metabolic disorders. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18:

E2187 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Gómez FA, Cárdenas C, Henríquez V, Marshall SH. Characterization of a functional toxin-antitoxin module in the genome of the fish pathogen Piscirickettsia salmonis. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2011;317:83–92. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Conceição T, Coelho C, de Lencastre H, Aires-de-Sousa M. High prevalence of biocide resistance determinants in Staphylococcus aureus isolates from three African countries. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;60:678–81. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Costliow ZA, Degnan PH. Thiamine acquisition strategies impact metabolism and competition in the gut microbe Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron. mSystems. 2017;2:1–17. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Chekabab SM, Harel J, Dozois CM. Interplay between genetic regulation of phosphate homeostasis and bacterial virulence. Virulence. 2014;5:786–93. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Sharp JA, Echague CG, Hair PS, Ward MD, Nyalwidhe JO, Geoghegan JA, et al. Staphylococcus aureus surface protein SdrE binds complement regulator factor H as an immune evasion tactic. PLoS One. 2012;7:

e38407 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Ghali I, Sofyan A, Ohmori H, Shinkai T, Mitsumori M. Diauxic growth of Fibrobacter succinogenes S85 on cellobiose and lactose. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2017;364:1–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Frankel MB, Hendrickx APA, Missiakas DM, Schneewind O. LytN, a murein hydrolase in the cross-wall compartment of Staphylococcus aureus, is involved in proper bacterial growth and envelope assembly. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:32593–605. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Hallet B, Sherratt DJ. Transposition and site-specific recombination: adapting DNA cut-and-paste mechanisms to a variety of genetic rearrangements. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1997;21:157–78. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- García-Gómez E, González-Pedrajo B, Camacho-Arroyo I. Role of sex steroid hormones in bacterial-host interactions. BioMed Res Int. 2013;2013:

928290 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Datta S, Costantino N, Zhou X, Court DL. Identification and analysis of recombineering functions from Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria and their phages. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:1626–31. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Schürch AC, Arredondo-Alonso S, Willems RJL, Goering RV. Whole genome sequencing options for bacterial strain typing and epidemiologic analysis based on single nucleotide polymorphism versus gene-by-gene-based approaches. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2018;24:350–4. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Ronald A. The etiology of urinary tract infection: traditional and emerging pathogens. Dis Mon. 2003;49:71–82. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- González-García S, Belo S, Dias AC, Rodrigues JV, Da Costa RR, Ferreira A, et al. Life cycle assessment of pigmeat production: Portuguese case study and proposal of improvement options. J Clean Prod. 2015;100:126–39. DOIGoogle Scholar

- Chopra I, Roberts M. Tetracycline antibiotics: mode of action, applications, molecular biology, and epidemiology of bacterial resistance. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2001;65:232–60. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Walker SW. Laboratory reference ranges. In: Endocrine self-assessment program. Washington, D.C.: Endocrine Society; 2015. p. 1–5 [cited 2019 Apr 29]. https://education.endocrine.org/system/files/ESAP%202015%20Laboratory%20Reference%20Ranges.pdf

- Linhares IM, Minis E, Robial R, Witkin SS. The human vaginal microbiome. In: Faintuch J, Faintuch S, editors. Microbiome and metabolome in diagnosis, therapy, and other strategic applications. London: Elsevier, Inc.; 2019. p. 109–14.

- Clarkson MR, Magee CN, Brenner BM. Chapter 2: Laboratory assessment of kidney disease. In: Clarkson MR, Magee CN, Brenner BM eds. Pocket companion to Brenner and Rector’s the Kidney 8th edition. London: Elsevier; 2011. p. 21–41 [cited 2019 Apr 29]. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9781416066408000026

- Frank LA, Mullins R, Rohrbach BW. Variability of estradiol concentration in normal dogs. Vet Dermatol. 2010;21:490–3. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Flores-Mireles AL, Walker JN, Caparon M, Hultgren SJ. Urinary tract infections: epidemiology, mechanisms of infection and treatment options. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2015;13:269–84. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Siboo IR, Chaffin DO, Rubens CE, Sullam PM. Characterization of the accessory Sec system of Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:6188–96. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- King NP, Beatson SA, Totsika M, Ulett GC, Alm RA, Manning PA, et al. UafB is a serine-rich repeat adhesin of Staphylococcus saprophyticus that mediates binding to fibronectin, fibrinogen and human uroepithelial cells. Microbiology (Reading). 2011;157:1161–75. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Arndt D, Grant JR, Marcu A, Sajed T, Pon A, Liang Y, et al. PHASTER: a better, faster version of the PHAST phage search tool. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44(W1):

W16-21 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Yahara K, Didelot X, Jolley KA, Kobayashi I, Maiden MCJ, Sheppard SK, et al. The landscape of realized homologous recombination in pathogenic bacteria. Mol Biol Evol. 2016;33:456–71. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Tristan A, Bes M, Meugnier H, Lina G, Bozdogan B, Courvalin P, et al. Global distribution of Panton-Valentine leukocidin—positive methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, 2006. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13:594–600. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Vincent C, Boerlin P, Daignault D, Dozois CM, Dutil L, Galanakis C, et al. Food reservoir for Escherichia coli causing urinary tract infections. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010;16:88–95. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Hedman P, Ringertz O, Lindström M, Olsson K. The origin of Staphylococcus saprophyticus from cattle and pigs. Scand J Infect Dis. 1993;25:57–60. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Verstappen KM, Willems E, Fluit AC, Duim B, Martens M, Wagenaar JA. Staphylococcus aureus nasal colonization differs among pig lineages and is associated with the presence of other staphylococcal species. Front Vet Sci. 2017;4:97. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Imperi F, Leoni L, Visca P. Antivirulence activity of azithromycin in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Front Microbiol. 2014;5:178. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Goerke C, Köller J, Wolz C. Ciprofloxacin and trimethoprim cause phage induction and virulence modulation in Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006;50:171–7. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Davies MR, McIntyre L, Mutreja A, Lacey JA, Lees JA, Towers RJ, et al. Atlas of group A streptococcal vaccine candidates compiled using large-scale comparative genomics. Nat Genet. 2019;51:1035–43. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Méric G, Mageiros L, Pensar J, Laabei M, Yahara K, Pascoe B, et al. Disease-associated genotypes of the commensal skin bacterium Staphylococcus epidermidis. Nat Commun. 2018;9:5034. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Dearborn AD, Dokland T. Mobilization of pathogenicity islands by Staphylococcus aureus strain Newman bacteriophages. Bacteriophage. 2012;2:70–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar