Volume 24, Number 2—February 2018

Research

New Parvovirus Associated with Serum Hepatitis in Horses after Inoculation of Common Biological Product

Cite This Article

Citation for Media

Abstract

Equine serum hepatitis (i.e., Theiler’s disease) is a serious and often life-threatening disease of unknown etiology that affects horses. A horse in Nebraska, USA, with serum hepatitis died 65 days after treatment with equine-origin tetanus antitoxin. We identified an unknown parvovirus in serum and liver of the dead horse and in the administered antitoxin. The equine parvovirus-hepatitis (EqPV-H) shares <50% protein identity with its phylogenetic relatives of the genus Copiparvovirus. Next, we experimentally infected 2 horses using a tetanus antitoxin contaminated with EqPV-H. Viremia developed, the horses seroconverted, and acute hepatitis developed that was confirmed by clinical, biochemical, and histopathologic testing. We also determined that EqPV-H is an endemic infection because, in a cohort of 100 clinically normal adult horses, 13 were viremic and 15 were seropositive. We identified a new virus associated with equine serum hepatitis and confirmed its pathogenicity and transmissibility through contaminated biological products.

Equine serum hepatitis (i.e., Theiler’s disease or idiopathic acute hepatitis) is a serious and often life-threatening disease of horses that was first described in 1919 in South Africa by Sir Arnold Theiler. Theiler observed hundreds of cases of a highly fatal form of hepatitis after experimental vaccination studies to prevent African horse sickness during which infectious virus was administered simultaneously with convalescent equine antiserum (1). The incidence of fulminant hepatitis among horses receiving antiserum in outbreaks of Theiler’s disease has been reported to be 1.4%–2.2% (1,2). Theiler’s disease has been described in horses in many areas of the world after treatment with a variety of equine serum products, including tetanus antitoxin (3–8), botulinum antitoxin (9), antiserum against Streptococcus equi (4,10), pregnant mare’s serum (4), and equine plasma (1,2,5,11). The clinical disease has a high rate of death, but some horses survive, and survivors have not been reported to have evidence of persistent liver disease (5,8).

Recently, 3 new flaviviruses were identified in horses (9,12,13). The first was the nonprimate hepacivirus (NPHV), later called equine hepacivirus (2,12), which is most closely related to hepatitis C virus (14). Natural NPHV infection in horses is reported to cause temporary elevation in liver enzymes, and negative-strand viral RNA was detected within hepatocytes (15–17). The 2 other flaviviruses of horses are Theiler’s disease–associated virus (TDAV) and equine pegivirus (EPgV), both members of the Pegivirus genus (14). TDAV was identified during an outbreak of acute clinical hepatitis in horses, 6 weeks after prophylactic administration of botulinum antitoxin of equine origin (9). EPgV is reported to be a common infection of horse populations of the United States and Western Europe, is not hepatotropic, and has not been associated with hepatic disease (13,16,18).

We identified a new parvovirus in the serum and liver of a horse that died in Nebraska, USA; the virus was also present in the tetanus antitoxin administered to the horse 65 days before disease onset. We acquired the complete viral genome from that horse and, considering its phylogenetic analysis, tentatively named the virus equine parvovirus hepatitis (EqPV-H). We describe the discovery of EqPV-H, its complete genome, infection prevalence, and virus transmission by inoculation of a commercial equine serum product resulting in hepatitis, thereby confirming EqPV-H association with equine hepatitis.

Sample Collection from the Index Horse

On November 6, 2013, a horse living in Nebraska, USA, was treated prophylactically with tetanus antitoxin (manufactured in Colorado, USA) 65 days before the onset of clinical signs of liver failure. After the horse died of Theiler’s disease in January 2014, serum and liver samples were collected and frozen or kept on ice before being shipped from the clinic of origin to Cornell University (Ithaca, NY, USA) for viral diagnostic testing. The remaining antitoxin in the vial that had been administered to the horse was shipped on ice for virologic testing. Aliquots of lots of commercial tetanus antitoxin to be used in the experimental inoculation were tested by PCR for EqPV-H, TDAV, NPHV, and EPgV as described previously (9,12,13).

Unbiased Amplification and High-Throughput Sequencing

We prepared liver suspension using ≈100 mg of liver tissue in 1 mL of phosphate-buffered saline and 3-mm steel beads using tissue lyser (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany). We centrifuged liver suspension and the antitoxin at 5,000 rpm for 10 min to remove the cell debris and filtered clarified supernatant through a 0.45-μ filter (Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA) and treated with nucleases to digest free nucleic acids for enrichment of viral nucleic acid. We performed sequencing library preparation, sequencing, and bioinformatics as described previously (19).

Complete Genome Sequencing and Genetic Analysis of EqPV-H

We acquired the complete genome of EqPV-H using a primer walking approach as previously described by us for several new animal parvoviruses, including bocaviruses (20–22). The genome of EqPV-H episome is available in GenBank (accession no. MG136722). To determine the sequence relationship between EqPV-H and other known parvovirus species, we used >1 representative virus member, including the reference genome from each species and its translated protein sequences, to generate sequence alignments. We generated a phylogenetic tree showing sequences used for the comparison and their GenBank accession numbers (Figure 1, panel A). The evolutionary history was inferred by using the maximum-likelihood method based on the Le_Gascuel_2008 model (23). The tree with the highest log likelihood is shown. We conducted evolutionary analyses in MEGA (24). DNA secondary structures of genomic termini were predicted by Mfold (25).

PCR and Serologic Assays for EqPV-H

We aligned the nonstructural (NS) protein and virion protein (VP) of EqPV-H to all known parvovirus proteins. We used nucleotide and amino acid motifs showing relative conservation among different virus lineages to make primers for screening samples for EqPV-H and related variants. All PCR mixtures used AmpliTaq Gold 360 master mix (catalog no. 4398881; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) and 2 μL of extracted nucleic acids. The EqPV-H NS gene PCR used primer pair EqPV ak1 (5′-GGAGAAGAGCGCAACAAATGCA-3′) and EqPV ak2 (5′-AAGACATTTCCGGCCGTGAC-3′) in the first round of PCR and the pair EqPV ak3 (5′-GCGCAACAAATGCAGCGGTTCGA-3′) and EqPV ak4 (5′-GGCCGTGACGACGGTGATATC-3′) in the second round of PCR. The EqPV-H VP gene PCR used primer pair EqPV ak5 (5′-GTCGCTGCATTCTGAGTCC-3′) and EqPV ak6 (5′-TGGGATTATACTGTCTACGGGT-3′) in the first round of PCR and the pair EqPV ak7 (5′-CTGCATTCTGAGTCCGTGGCC-3′) and EqPV ak8 (5′-CTGTCTACGGGTATCCCATACGTA-3′) in the second round of PCR.

Luciferase Immunoprecipitation System Assay for EqPV Serology

We cloned the C terminus of the EqPV-H capsid protein into pREN2 plasmid for making Renilla luciferase fused antigen for a Luciferase Immunoprecipitation System (LIPS) assay. In brief, we amplified the VP1 gene of EqPV-H using primers EqPV LIPSF1 (5′-AGTAAAGTCAATGGACACCA-3′) and EqPV LIPSR1 (5′-GGATCGTGGTATGAGTTC-3′). We sequenced PCR product and then used it as a template to make inserts for LIPS assay using primers with flanking restriction sites, EqPV LIPS BamHI (5′-GAGGGATCCCATGCTTTACCGTATGATC-3′) and EqPV-H LIPS XhoI (5′-GAGCTCGAGTCAGAACTGACAGTATTGGTTC-3′. Inserts were subsequently sequenced, digested, and ligated into pREN-2 expression vector. Details of LIPS antigen preparation and serologic testing have been described previously (12,26–28).

Experimental Infection of Horses

We selected 2 healthy 18- and 20-year-old mares from the Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine teaching and research herd that were negative by PCR for EqPV-H, TDAV, and NPHV. We inoculated the horses 4 months apart with 2 lots of tetanus antitoxin that were PCR positive for EqPV-H. These sample lots were selected because they had been reported to us to have been associated with additional cases of Theiler’s disease. We pooled both lots for inoculation so that each horse received the identical inoculum. In each experimental horse, we administered 5.0 mL of the pooled tetanus antitoxin intravenously and 5.0 mL subcutaneously in the neck. We collected blood samples for biochemical analysis in the experimental inoculation study from the jugular vein into 7-mL sodium heparin tubes (BD Vacutainer; Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) and promptly submitted them to the New York State Animal Health Diagnostic Center at Cornell University for biochemical tests indicative of hepatic disease: aspartate aminotransferase (AST), sorbitol dehydrogenase (SDH), γ-glutamyltransferase (GGT), total bile acids, and bilirubin. Tests were performed using a Hitachi Mod P 800 (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, USA).

We performed liver biopsies after sedation with 5 mg detomidine administered intravenously; local anesthetic (2% lidocaine) was injected subcutaneously at the planned insertion site of the percutaneous biopsy instrument (Tru-Cut Biopsy Needle; Travenol Laboratories, Deerfield, IL., USA). We determined the location of the biopsy needle insertion by ultrasonographic visualization of the liver. We placed samples in formalin for histopathologic studies and submitted fresh liver tissue to the same laboratory for quantitative PCR. The case–control and experimental inoculation studies were approved in full by the Cornell University Animal Research Committee (IACUC no. 2014-0024).

Identification of EqPV-H in Horse with Theiler’s Disease

Serum and liver samples from the deceased horse obtained postmortem and from the administered tetanus antitoxin tested negative for the 3 recently identified horse flaviviruses, NPHV, TDAV, and EPgV (29). We used an unbiased amplification and high-throughput sequencing approach to identify known and new viruses in the antitoxin and liver sample (19,23,30). Bioinformatics of sequence data revealed a 4.5-kb base assembled sequence in the horse liver sample that showed distant yet significant protein similarity with known bovine and porcine parvoviruses. Thereafter, the in silico assembled sequence data were used to design primers for amplifying the complete genome of the new parvovirus, tentatively named EqPV-H. Considering the presence of high virus titer in the liver sample and the precedent of finding virus episomes in tissue for related parvoviruses (20), we used an inverse PCR–based approach to acquire the complete virus genome. The inverse PCR confirmed that EqPV-H exists as episomes in the liver tissue.

The complete episome of EqPV-H comprises 5,308 nt and is predicted to code 2 large open reading frames whose proteins are related to the NS proteins and the structural proteins (VPs) of known animal parvoviruses (Figures 1, 2). If the first nucleotide of NS protein is considered to be genome position 1, the NS protein is coded by nucleotide positions 1–1,779, followed by an intergenic region of 21 nt, and the VPs are coded by nucleotide positions 1,801–4,722. An intergenic region of 583 nt connects the end of VP coding region to the NS coding region in the episomal genome form of EqPV-H. The genomic termini of parvoviruses play an important role in virus replication and translation. Similar to known animal parvoviruses, the DNA folding programs predicted 1 long hairpin and other small hairpins in the intergenic region of EqPV-H (Figure 2). Attempts to propagate the virus in cell culture using the serum and liver samples of infected horses have been unsuccessful.

EqPV-H genome organization and genetic relatedness to known viruses suggest its classification as a prototype of new species in the genus Copiparvovirus (Figure 1, panel A). Other members of the genus Copiparvovirus include parvoviruses that infect pigs, cows, and sea lions and a recently identified virus found in horse cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), horse parvovirus–CSF (31). Since the NS proteins of parvoviruses are relatively more conserved than the VP, we used the NS protein of EqPV-H for its phylogenetic analysis. Results indicate that EqPV-H is distinct, yet most closely related to different species of copiparvoviruses (Figure 1, panel A). The EqPV-H is more closely related to pig and cow copiparvovirus than to the only other horse copiparvovirus, indicating different evolutionary origins of these 2 horse viruses. This NS gene–based phylogenetic analysis was further confirmed using VP gene–based phylogenetic analysis (data not shown).

Infection Prevalence, Disease Association, and Molecular Epidemiology

To determine the infection prevalence of EqPV-H, we tested 100 horse serum samples of convenience submitted to the New York State Animal Health Diagnostic Center at Cornell University for nonclinical reasons. PCRs targeting the NS and VP region of EqPV-H identified 13 of 100 horses positive for EqPV-H viremia. We also tested these samples for EqPV-H IgG using partial VP1 as antigen in the LIPS assay. We determined that all 13 viremic horses had IgG. In addition, 2 nonviremic horses were seropositive, indicating clearance of EqPV-H viremia. We then tested the 13 virus-positive samples biochemically for evidence of liver disease using GGT as a marker; all results were within normal range. Genetic analysis of EqPV-H variants found in all the studied serum samples indicated a very low level of genetic diversity (<2% nt differences in NS and VP sequences) among isolates.

Experimental Inoculation of Commercial Tetanus Antitoxin

To confirm transmission of EqPV-H by tetanus antitoxin, we inoculated 2 clinically normal mares with 10 mL of tetanus antitoxin positive for EqPV-H. The 2 horses were confirmed PCR negative for EqPV-H, TDAV, and NPHV nucleic acids and LIPS negative for EqPV-H antibody. At weekly intervals after inoculation, we tested both experimentally inoculated horses for NPHV, TDAV, and EqPV-H nucleic acids by quantitative PCR, for EqPV-H antibodies by LIPS, and for biochemical evidence of liver disease (Figure 3). Both horses remained PCR negative for EqPV-H nucleic acids on weekly sampling until 47 and 48 days postinoculation (dpi), at which time both horses became PCR positive for EqPV-H. Consecutive weekly samples demonstrated increasing viremia in both horses; viremia peaked at 81 and 96 dpi. Thereafter, viremia gradually decreased, but EqPV-H was still detected in the serum of both horses at study termination (123 and 125 dpi). Antibodies against EqPV-H capsid protein were first detected at 88 and 89 dpi in the 2 infected horses. Both horses remained PCR negative for NPHV and TDAV at study termination.

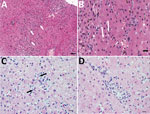

In horse 1, serum biochemical evidence of liver disease was first observed at 82 dpi, when all test parameters except bile acids and total bilirubin showed marked increases (Figure 3). Samples were then tested daily or every other day; bile acids and bilirubin were increased at 84 dpi (Figure 3). At 87 dpi, horse 1 became icteric and depressed and developed orange urine (bilirubinuria). Abnormalities in biochemical parameters increased further until 90 dpi, after which values started to return to normal. Values were normal by 98 dpi except for GGT, which returned to normal range at 114 dpi. Clinical icterus and discolored urine were not observed after 94 dpi. A liver biopsy sample obtained at 82 dpi showed lymphocytic lobular atrophy (Figure 4, panel A) and necrotic hepatocytes (Figure 4, panel B).

Horse 2 first showed abnormal serum biochemistry values at 96 dpi; AST, SDH, GGT, bile acids, and total bilirubin increased gradually until 105 dpi, when all biochemical values began decreasing and were normal by 118 dpi, except for GGT, which remained mildly elevated at the conclusion of the study (123 dpi). A liver biopsy sample obtained at 100 dpi had lymphocytes surrounding clusters of necrotic hepatocytes and lymphocytic satellitosis (Figure 4, panel C). Portal tracts were also infiltrated with small numbers of lymphocytes that breached the limiting plate (Figure 4, panel D).

The previously unidentified horse parvovirus EqPV-H we describe represents the prototype of a new virus species of genus Copiparvovirus. Although a new parvovirus in the genus Copiparvovirus was recently found in a CSF sample of a horse with neurologic signs, EqPV-H is genetically very distinct from that virus (31). EqPV-H is genetically more similar to other ungulate copiparvoviruses than the horse parvovirus–CSF. Parvoviruses are ubiquitous and are proposed to have a wide range of effects on their hosts, ranging from severe disease to nonpathogenic infections (32). The pathogenesis of parvoviruses is generally associated with their predilection for actively dividing cells and different parvoviruses have different organ tropism (32). Parvovirus hepatitis in other species is rare, although parvovirus B19 can be associated with acute hepatitis in humans after transfusion of contaminated blood products (33,34).

Although the overall incidence of clinically recognized serum hepatitis in adult horses receiving tetanus antitoxin is low, tetanus antitoxin has been the most commonly reported blood product associated with the disease in the United States for the past 50 years (3,4,6–8). Commercial tetanus antitoxin is heat treated (60°C for 1 h) to inactivate virus, and phenol and thimeresol are added as preservatives. Such treatments could leave detectable viral nucleic acids that would be nontransmissible. However, the 2 successful transmissions of EqPV-H to experimentally inoculated horses confirmed that EqPV-H can be transmitted from heat-treated commercially available tetanus antitoxin. Although this form of heat treatment is known to inactivate heat-labile viruses, such as lentiviruses (35), in blood products, parvoviruses and especially animal parvoviruses are very resistant to heat inactivation and solvent detergent treatments (35–38).

The incubation period for onset of biochemical disease after experimental inoculation of PCR-positive tetanus antitoxin to the 2 horses was longer (82 and 94 days) than most reported clinical cases of equine serum hepatitis. Clinical cases typically occur 6–10 weeks after blood product inoculation, but cases have been reported as long as 14 weeks after blood product administration (5,7). Complete recovery of both horses in the experimental study was not surprising because rapid (3–7 days) recovery occurs in some horses with Theiler’s disease (5,8). Microscopic findings in clinically affected horses with serum hepatitis consistently include widespread centrilobular to midzonal hepatocellular necrosis with hemorrhage; portal areas have mild inflammatory infiltrate, primarily monocytes and lymphocytes, and moderate bile duct proliferation (39,40). Liver enzymes, including SDH and AST, are increased several fold, and GGT is increased but often not to the same magnitude as the hepatocellular enzymes (7,8). We therefore believe that the incubation period after tetanus antitoxin administration, combined with serum chemistry and histopathologic finding in the 2 experimentally infected horses, is compatible with prior reports on equine serum hepatitis (3–8,11).

The virus and serologic survey findings of EqPV-H viremia in 13% of horses without biochemical evidence of liver disease suggests that most horses that become infected with EqPV-H do not develop clinical disease. This finding would be compatible with epidemiologic data on Theiler’s disease outbreaks in which clinical hepatitis develops in only 1.4%–2.2% of horses receiving equine blood products (1,2). One limitation of our study was that we could not determine the exact chronicity of infection in the horses in the serologic study and if these horses had biochemical evidence of liver disease at some prior point during infection. Although our limited study indicates low genetic diversity among EqPV-H isolated from different horses, follow-up studies that include horses living in different geographic areas are necessary to define the true prevalence and genetic diversity of EqPV-H. Why some horses develop severe and often fatal disease after EqPV-H infection and others do not also remains unknown and requires further investigation.

Several findings in this study suggest that EqPV-H infections in horses can often be persistent. In the serologic/virus prevalence study, only 2 horses with EqPV-H antibody were virus negative, and the 13 viremic horses all had antibody. In addition, both experimentally infected horses were virus positive after 123 days, despite having high antibody levels. We have no data on the ability of antibody specific for EqPV-H to neutralize the virus or on the role the antibody might play in maintaining infection. Finally, retrospective testing of administered antitoxin and serum samples of recipient horses indicated presence of EqPV-H in all samples that tested positive for TDAV infection in our previous study (9). We believe that because the previous study used RNA-only viral metagenomics, the EqPV-H (a DNA virus) remained elusive.

In summary, information from this study suggests that EqPV-H can cause serum hepatitis (Theiler’s disease) in horses. EqPV-H in horse serum or plasma products should be of concern.

Dr. Divers is the endowed Steffen Professor of Veterinary Medicine at Cornell University, Ithaca. His primary research interests are equine infectious diseases and disorders of the equine liver.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Nicholas A. Hollinshead and Nancy Zylich for Figure 4 preparation.

This work was supported in part by the National Institute of Food and Agriculture, US Department of Agriculture, under award no. 2016-67015-24765 and the Research Institute at Nationwide Children’s Hospital. The Zweig Equine Research Fund and the Niarchos Family also provided funding for this study.

References

- Theiler A. Acute liver atrophy and parenchymatous hepatitis in horses. Reports of the Director of Veterinary Research. 1918;5&6:7–99.

- Marsh H. Losses of undetermined cause following an outbreak of equine encephalomyelitis. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1937;91:88–93.

- Rose JA, Immenschuh RD, Rose EM. Serum hepatitis in the horse. Proceedings of the Twentieth Annual Conference of the American Association of Equine Practitioners. Lexington (KY): American Association of Equine Practitioners; 1974. p. 175–85.

- Step DL, Blue JT, Dill SG. Penicillin-induced hemolytic anemia and acute hepatic failure following treatment of tetanus in a horse. Cornell Vet. 1991;81:13–8.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Messer NT IV, Johnson PJ. Idiopathic acute hepatic disease in horses: 12 cases (1982-1992). J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1994;204:1934–7.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Guglick MA, MacAllister CG, Ely RW, Edwards WC. Hepatic disease associated with administration of tetanus antitoxin in eight horses. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1995;206:1737–40.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Chandriani S, Skewes-Cox P, Zhong W, Ganem DE, Divers TJ, Van Blaricum AJ, et al. Identification of a previously undescribed divergent virus from the Flaviviridae family in an outbreak of equine serum hepatitis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:E1407–15. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Aleman M, Nieto JE, Carr EA, Carlson GP. Serum hepatitis associated with commercial plasma transfusion in horses. J Vet Intern Med. 2005;19:120–2. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Burbelo PD, Dubovi EJ, Simmonds P, Medina JL, Henriquez JA, Mishra N, et al. Serology-enabled discovery of genetically diverse hepaciviruses in a new host. J Virol. 2012;86:6171–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Kapoor A, Simmonds P, Cullen JM, Scheel TK, Medina JL, Giannitti F, et al. Identification of a pegivirus (GB virus-like virus) that infects horses. J Virol. 2013;87:7185–90. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Scheel TK, Simmonds P, Kapoor A. Surveying the global virome: identification and characterization of HCV-related animal hepaciviruses. Antiviral Res. 2015;115:83–93. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Pfaender S, Cavalleri JM, Walter S, Doerrbecker J, Campana B, Brown RJ, et al. Clinical course of infection and viral tissue tropism of hepatitis C virus-like nonprimate hepaciviruses in horses. Hepatology. 2015;61:447–59. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Scheel TK, Kapoor A, Nishiuchi E, Brock KV, Yu Y, Andrus L, et al. Characterization of nonprimate hepacivirus and construction of a functional molecular clone. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:2192–7. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Ramsay JD, Evanoff R, Wilkinson TE Jr, Divers TJ, Knowles DP, Mealey RH. Experimental transmission of equine hepacivirus in horses as a model for hepatitis C virus. Hepatology. 2015;61:1533–46. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Lyons S, Kapoor A, Schneider BS, Wolfe ND, Culshaw G, Corcoran B, et al. Viraemic frequencies and seroprevalence of non-primate hepacivirus and equine pegiviruses in horses and other mammalian species. J Gen Virol. 2014;95:1701–11. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Kapoor A, Kumar A, Simmonds P, Bhuva N, Singh Chauhan L, Lee B, et al. Virome analysis of transfusion recipients reveals a novel human virus that shares genomic features with hepaciviruses and pegiviruses. MBio. 2015;6:e01466–15. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Kapoor A, Hornig M, Asokan A, Williams B, Henriquez JA, Lipkin WI. Bocavirus episome in infected human tissue contains non-identical termini. PLoS One. 2011;6:e21362. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Kapoor A, Mehta N, Dubovi EJ, Simmonds P, Govindasamy L, Medina JL, et al. Characterization of novel canine bocaviruses and their association with respiratory disease. J Gen Virol. 2012;93:341–6. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Kapoor A, Mehta N, Esper F, Poljsak-Prijatelj M, Quan PL, Qaisar N, et al. Identification and characterization of a new bocavirus species in gorillas. PLoS One. 2010;5:e11948. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Kapoor A, Lipkin WI. Virus discovery in the 21st century. Chichester (UK): John Wiley & Sons; 2014. DOIGoogle Scholar

- Tamura K, Stecher G, Peterson D, Filipski A, Kumar S. MEGA6: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis version 6.0. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30:2725–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Zuker M. Mfold web server for nucleic acid folding and hybridization prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3406–15. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Burbelo PD, Ragheb JA, Kapoor A, Zhang Y. The serological evidence in humans supports a negligible risk of zoonotic infection from porcine circovirus type 2. Biologicals. 2013;41:430–4. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Burbelo PD, Ching KH, Morse CG, Alevizos I, Bayat A, Cohen JI, et al. Altered antibody profiles against common infectious agents in chronic disease. PLoS One. 2013;8:e81635. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Burbelo PD, Ching KH, Esper F, Iadarola MJ, Delwart E, Lipkin WI, et al. Serological studies confirm the novel astrovirus HMOAstV-C as a highly prevalent human infectious agent. PLoS One. 2011;6:e22576. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Hartlage AS, Cullen JM, Kapoor A. The strange, expanding world of animal hepaciviruses. Annu Rev Virol. 2016;3:53–75. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Kapoor A, Simmonds P, Dubovi EJ, Qaisar N, Henriquez JA, Medina J, et al. Characterization of a canine homolog of human Aichivirus. J Virol. 2011;85:11520–5. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Li L, Giannitti F, Low J, Keyes C, Ullmann LS, Deng X, et al. Exploring the virome of diseased horses. J Gen Virol. 2015;96:2721–33. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Kailasan S, Agbandje-McKenna M, Parrish CR. Parvovirus family conundrum: what makes a killer? Annu Rev Virol. 2015;2:425–50. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Bihari C, Rastogi A, Saxena P, Rangegowda D, Chowdhury A, Gupta N, et al. Parvovirus B19 associated hepatitis. Hepat Res Treat. 2013;2013:472027.

- Hatakka A, Klein J, He R, Piper J, Tam E, Walkty A. Acute hepatitis as a manifestation of parvovirus B19 infection. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49:3422–4. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Caruso C, Gobbi E, Biosa T, Andra’ M, Cavallazzi U, Masoero L. Evaluation of viral inactivation of pseudorabies virus, encephalomyocarditis virus, bovine viral diarrhea virus and porcine parvovirus in pancreatin of porcine origin. J Virol Methods. 2014;208:79–84. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Roberts PL, Hart H. Comparison of the inactivation of canine and bovine parvovirus by freeze-drying and dry-heat treatment in two high purity factor VIII concentrates. Biologicals. 2000;28:185–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Mani B, Gerber M, Lieby P, Boschetti N, Kempf C, Ros C. Molecular mechanism underlying B19 virus inactivation and comparison to other parvoviruses. Transfusion. 2007;47:1765–74. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Blümel J, Stühler A, Dichtelmüller H. Kinetics of inactivating human parvovirus B19 and porcine parvovirus by dry-heat treatment. Transfusion. 2008;48:790–1. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Qualls CW, Gribble DH. Equine serum hepatitis: a morphologic study. Lab Invest. 1976;34:330.

- Robinson M, Gopinath C, Hughes DL. Histopathology of acute hepatitis in the horse. J Comp Pathol. 1975;85:111–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

Figures

Cite This Article1Deceased.

Table of Contents – Volume 24, Number 2—February 2018

| EID Search Options |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Please use the form below to submit correspondence to the authors or contact them at the following address:

Amit Kapoor, Ohio State University, Department of Pediatrics, Center for Vaccines and Immunity, Research Institute at Nationwide Children’s Hospital, 700 Children’s Dr, Columbus, OH 43205, USA

Top