Volume 27, Number 5—May 2021

Research

Susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 of Cell Lines and Substrates Commonly Used to Diagnose and Isolate Influenza and Other Viruses

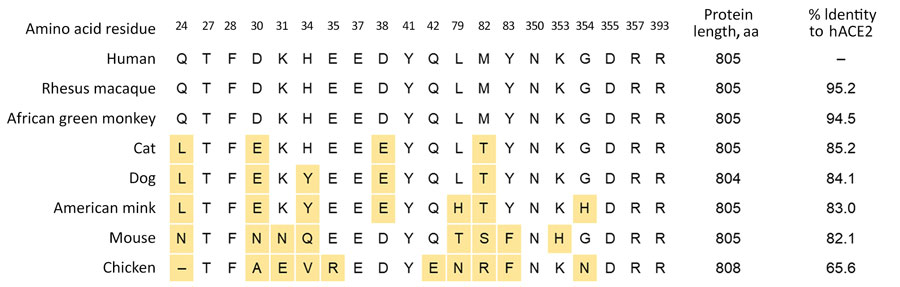

Figure 10

Figure 10. Aligned ACE2 protein sequences from human, rhesus macaque, African green monkey, cat, dog, American mink, mouse, and chicken cells in study of susceptibility to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) of cell lines and substrates used to diagnose and isolate influenza and other viruses. Residues involved in interaction with SARS-CoV-2 spike protein (41–44) shown using hACE2 numbering; yellow indicates residues varying from hACE2. Dash indicates gap in alignment. Percentage identity to hACE2 across the entire protein is shown. ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme 2; cACE2, canine ACE2; hACE2, human ACE2.

References

- Kim D, Quinn J, Pinsky B, Shah NH, Brown I. Rates of co-infection between SARS-CoV-2 and other respiratory pathogens. JAMA. 2020;323:2085–6. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Li Z, Chen ZM, Chen LD, Zhan YQ, Li SQ, Cheng J, et al. Coinfection with SARS-CoV-2 and other respiratory pathogens in patients with COVID-19 in Guangzhou, China. J Med Virol. 2020;92:2381–3. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Konala VM, Adapa S, Naramala S, Chenna A, Lamichhane S, Garlapati PR, et al. A case series of patients coinfected with influenza and COVID-19. J Investig Med High Impact Case Rep. 2020;8:

2324709620934674 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Yue H, Zhang M, Xing L, Wang K, Rao X, Liu H, et al. The epidemiology and clinical characteristics of co-infection of SARS-CoV-2 and influenza viruses in patients during COVID-19 outbreak. J Med Virol. 2020;92:2870–3. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Harcourt J, Tamin A, Lu X, Kamili S, Sakthivel SK, Murray J, et al. severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 from patient with coronavirus disease, United States. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26:1266–73. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Xie X, Muruato A, Lokugamage KG, Narayanan K, Zhang X, Zou J, et al. An infectious cDNA clone of SARS-CoV-2. Cell Host Microbe. 2020;27:841–848.e3. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Hoffmann M, Kleine-Weber H, Pöhlmann S. A multibasic cleavage site in the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 is essential for infection of human lung cells. Mol Cell. 2020;78:779–784.e5. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Chu H, Hu B, Huang X, Chai Y, Zhou D, Wang Y, et al. Host and viral determinants for efficient SARS-CoV-2 infection of the human lung. Nat Commun. 2021;12:134. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Johnson BA, Xie X, Bailey AL, Kalveram B, Lokugamage KG, Muruato A, et al. Loss of furin cleavage site attenuates SARS-CoV-2 pathogenesis. Nature. 2021;591:293–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Lu X, Wang L, Sakthivel SK, Whitaker B, Murray J, Kamili S, et al. US CDC Real-time reverse transcription PCR panel for detection of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26:1654–65. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Zhou B, Thao TTN, Hoffmann D, Taddeo A, Ebert N, Labroussaa F, et al. SARS-CoV-2 spike D614G variant confers enhanced replication and transmissibility. Nature. 2021; [Epub ahead of print]. DOIGoogle Scholar

- Matrosovich M, Matrosovich T, Carr J, Roberts NA, Klenk HD. Overexpression of the alpha-2,6-sialyltransferase in MDCK cells increases influenza virus sensitivity to neuraminidase inhibitors. J Virol. 2003;77:8418–25. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Takada K, Kawakami C, Fan S, Chiba S, Zhong G, Gu C, et al. A humanized MDCK cell line for the efficient isolation and propagation of human influenza viruses. Nat Microbiol. 2019;4:1268–73. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Wang W, Xu Y, Gao R, Lu R, Han K, Wu G, et al. Detection of SARS-CoV-2 in different types of clinical specimens. JAMA. 2020;323:1843–4. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Cheung KS, Hung IFN, Chan PPY, Lung KC, Tso E, Liu R, et al. Gastrointestinal manifestations of SARS-CoV-2 infection and virus load in fecal samples from a Hong Kong cohort: systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2020;159:81–95. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Young BE, Ong SWX, Kalimuddin S, Low JG, Tan SY, Loh J, et al.; Singapore 2019 Novel Coronavirus Outbreak Research Team. Singapore 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak research team. epidemiologic features and clinical course of patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 in Singapore. JAMA. 2020;323:1488–94. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Xu Y, Li X, Zhu B, Liang H, Fang C, Gong Y, et al. Characteristics of pediatric SARS-CoV-2 infection and potential evidence for persistent fecal viral shedding. Nat Med. 2020;26:502–5. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Zheng S, Fan J, Yu F, Feng B, Lou B, Zou Q, et al. Viral load dynamics and disease severity in patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 in Zhejiang province, China, January-March 2020: retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2020;369:m1443. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Tang A, Tong ZD, Wang HL, Dai YX, Li KF, Liu JN, et al. Detection of novel coronavirus by RT-PCR in stool specimen from asymptomatic child, China. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26:1337–9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- COVID-19 Investigation Team. Clinical and virologic characteristics of the first 12 patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in the United States. Nat Med. 2020;26:861–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Wentworth DE, Holmes KV. Coronavirus binding and entry. Thiel V, editor. Coronaviruses: molecular and cellular biology. Norfolk (UK): Caister Academic Press; 2007. p. 3–31

- Zhang H, Penninger JM, Li Y, Zhong N, Slutsky AS. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) as a SARS-CoV-2 receptor: molecular mechanisms and potential therapeutic target. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46:586–90. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Abdel-Moneim AS, Abdelwhab EM. Evidence for SARS-CoV-2 infection of animal hosts. Pathogens. 2020;9:

E529 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Oreshkova N, Molenaar RJ, Vreman S, Harders F, Oude Munnink BB, Hakze-van der Honing RW, et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection in farmed minks, the Netherlands, April and May 2020. Euro Surveill. 2020;25:

2001005 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Munster VJ, Feldmann F, Williamson BN, van Doremalen N, Pérez-Pérez L, Schulz J, et al. Respiratory disease in rhesus macaques inoculated with SARS-CoV-2. Nature. 2020;585:268–72. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Bosco-Lauth AM, Hartwig AE, Porter SM, Gordy PW, Nehring M, Byas AD, et al. Experimental infection of domestic dogs and cats with SARS-CoV-2: Pathogenesis, transmission, and response to reexposure in cats. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117:26382–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Halfmann PJ, Hatta M, Chiba S, Maemura T, Fan S, Takeda M, et al. Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in domestic cats. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:592–4. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Singla R, Mishra A, Joshi R, Jha S, Sharma AR, Upadhyay S, et al. Human animal interface of SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) transmission: a critical appraisal of scientific evidence. Vet Res Commun. 2020;44:119–30. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Chu H, Chan JF, Yuen TT, Shuai H, Yuan S, Wang Y, et al. Comparative tropism, replication kinetics, and cell damage profiling of SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV with implications for clinical manifestations, transmissibility, and laboratory studies of COVID-19: an observational study. Lancet Microbe. 2020;1:e14–23. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Barr IG, Rynehart C, Whitney P, Druce J. SARS-CoV-2 does not replicate in embryonated hen’s eggs or in MDCK cell lines. Euro Surveill. 2020;25:

2001122 . DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar - Hattermann K, Müller MA, Nitsche A, Wendt S, Donoso Mantke O, Niedrig M. Susceptibility of different eukaryotic cell lines to SARS-coronavirus. Arch Virol. 2005;150:1023–31. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Kaye M, Druce J, Tran T, Kostecki R, Chibo D, Morris J, et al. SARS-associated coronavirus replication in cell lines. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:128–33. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Yamashita M, Yamate M, Li GM, Ikuta K. Susceptibility of human and rat neural cell lines to infection by SARS-coronavirus. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;334:79–85. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Drosten C, Günther S, Preiser W, van der Werf S, Brodt HR, Becker S, et al. Identification of a novel coronavirus in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1967–76. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Gillim-Ross L, Taylor J, Scholl DR, Ridenour J, Masters PS, Wentworth DE. Discovery of novel human and animal cells infected by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus by replication-specific multiplex reverse transcription-PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:3196–206. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Hattermann K, Müller MA, Nitsche A, Wendt S, Donoso Mantke O, Niedrig M. Susceptibility of different eukaryotic cell lines to SARS-coronavirus. Arch Virol. 2005;150:1023–31. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Ksiazek TG, Erdman D, Goldsmith CS, Zaki SR, Peret T, Emery S, et al.; SARS Working Group. A novel coronavirus associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1953–66. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Mossel EC, Huang C, Narayanan K, Makino S, Tesh RB, Peters CJ. Exogenous ACE2 expression allows refractory cell lines to support severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus replication. J Virol. 2005;79:3846–50. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Severson WE, Shindo N, Sosa M, Fletcher T III, White EL, Ananthan S, et al. Development and validation of a high-throughput screen for inhibitors of SARS CoV and its application in screening of a 100,000-compound library. J Biomol Screen. 2007;12:33–40. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Yen YT, Liao F, Hsiao CH, Kao CL, Chen YC, Wu-Hsieh BA. Modeling the early events of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection in vitro. J Virol. 2006;80:2684–93. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Yan R, Zhang Y, Li Y, Xia L, Guo Y, Zhou Q. Structural basis for the recognition of SARS-CoV-2 by full-length human ACE2. Science. 2020;367:1444–8. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Wang Q, Zhang Y, Wu L, Niu S, Song C, Zhang Z, et al. Structural and functional basis of SARS-CoV-2 entry by using human ACE2. Cell. 2020;181:894–904.e9. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Lan J, Ge J, Yu J, Shan S, Zhou H, Fan S, et al. Structure of the SARS-CoV-2 spike receptor-binding domain bound to the ACE2 receptor. Nature. 2020;581:215–20. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Shang J, Ye G, Shi K, Wan Y, Luo C, Aihara H, et al. Structural basis of receptor recognition by SARS-CoV-2. Nature. 2020;581:221–4. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Enserink M. Coronavirus rips through Dutch mink farms, triggering culls. Science. 2020;368:1169. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Molenaar RJ, Vreman S, Hakze-van der Honing RW, Zwart R, de Rond J, Weesendorp E, et al. Clinical and pathological findings in SARS-CoV-2 disease outbreaks in farmed mink (Neovison vison). Vet Pathol. 2020;57:653–7. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Hammer AS, Quaade ML, Rasmussen TB, Fonager J, Rasmussen M, Mundbjerg K, et al. SARS-CoV-2 Transmission between mink (Neovison vison) and humans, Denmark. Emerg Infect Dis. 2021;27:547–51. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Oude Munnink BB, Sikkema RS, Nieuwenhuijse DF, Molenaar RJ, Munger E, Molenkamp R, et al. Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 on mink farms between humans and mink and back to humans. Science. 2021;371:172–7. DOIPubMedGoogle Scholar

Page created: February 24, 2021

Page updated: April 20, 2021

Page reviewed: April 20, 2021

The conclusions, findings, and opinions expressed by authors contributing to this journal do not necessarily reflect the official position of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the Public Health Service, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or the authors' affiliated institutions. Use of trade names is for identification only and does not imply endorsement by any of the groups named above.