Dominican Republic

CDC Yellow Book 2024

Popular ItinerariesDestination Overview

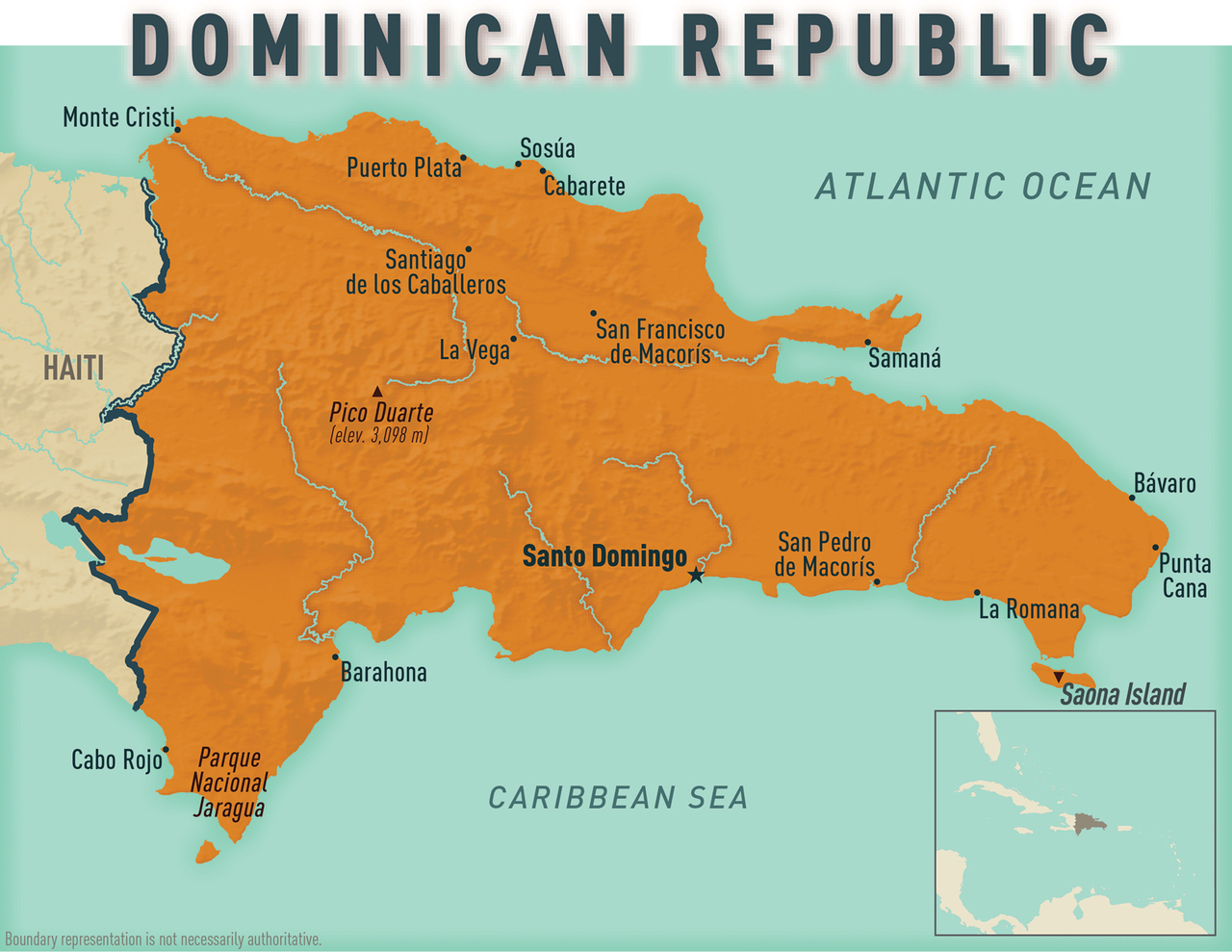

The Dominican Republic—the second-largest Caribbean nation, both by area and by population—covers the eastern two-thirds of the Caribbean Island of Hispaniola; Haiti comprises the western third. The capital city, Santo Domingo, is located on the southern coast of the island (see Map 10-07). Although English is spoken in most tourist areas, Spanish is the official language. Approximately 250,000 US citizens call the Dominican Republic home. Average temperatures range from 73.5°F (23°C) in January to 80°F (26.5°C) in August. The island receives more rain during May–November, and tropical storms or hurricanes are possible.

In 2018, >6.5 million foreign tourists, including ≈3 million from Canada and the United States, visited the Dominican Republic, making it the most visited destination in the Caribbean. The Dominican Republic offers a diverse geography of beaches, mountain ranges (including the highest point in the Caribbean, Pico Duarte [3,098 m; 10,164 ft]), sugar cane and tobacco plantations, and farmland. Most tourism is concentrated in the east of the country around Bávaro and Punta Cana, which offer all-inclusive beach resorts.

Whale watching is popular seasonally near the northeastern area, Samaná, and kitesurfing and windsurfing attract visitors to the northern areas of Puerto Plata, Sosúa, and Cabarete. Santo Domingo has an attractive colonial district that contains many historical sites dating back to Christopher Columbus’s arrival in the New World. Few travelers visit other parts of the country, where tourist infrastructure is limited or nonexistent.

Infectious Disease Risks

All travelers should be up to date on routine vaccinations, including coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and seasonal influenza. Cases of vaccine-preventable diseases have been reported among the local population and unvaccinated tourists from Europe and other parts of the world. Travelers also should be vaccinated against hepatitis A.

Enteric Infections & Diseases

Cholera

The most recent cholera outbreak in the Dominican Republic occurred in 2018 in Independencia Province and was readily contained. Since then, no cholera cases have been reported. For current recommendations for travelers to the Dominican Republic, visit the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Travelers’ Health website.

Travelers’ Diarrhea

Although food hygiene at large, all-inclusive resorts and popular tourist locations has improved in the past few years, travelers’ diarrhea (TD) continues to be the most common health problem for visitors to the Dominican Republic (see Sec. 2, Ch. 6, Travelers’ Diarrhea). Food purchased on the street or sold on beaches by informal sellers presents a greater risk for illness (see Sec. 2, Ch. 8, Food & Water Precautions). Advise travelers not to eat raw or undercooked seafood, and remind them to drink only purified, bottled water. Ice served in well-established tourist locations is usually made from purified water and safe to consume. Ice might not be safe in remote or non-tourist areas, however.

Typhoid Fever

Travelers should be vaccinated against typhoid fever, especially anyone visiting friends or relatives (see Sec. 5, Part 1, Ch. 24, Typhoid & Paratyphoid Fever).

Respiratory Infections & Diseases

Coronavirus Disease 2019

All travelers going to the Dominican Republic should be up to date with their COVID-19 vaccines.

Tuberculosis

In 2019, the National Tuberculosis (TB) Control Program reported an incidence of 30.4 TB cases per 100,000 inhabitants. Although there is community spread of TB, no reports exist of travelers or tourists becoming infected with TB while visiting the Dominican Republic.

Sexually Transmitted Infections & HIV

Although illegal, commercial sex workers (CSW) are found throughout the Dominican Republic; Samaná, Sosúa, and Puerto Plata are known sex tourism destinations. HIV prevalence among female CSW is ≈3%, and up to 6% in some areas; syphilis (12%), hepatitis B virus (2.4%), and hepatitis C virus (0.9%) are also concerns. Among men who have sex with men, HIV prevalence is ≤4.5% and active syphilis ≤13.9%. Travelers should avoid sexual intercourse with CSW and always use condoms with any partner whose HIV or sexually transmitted infection status is unknown (see Sec. 9, Ch. 12, Sex & Travel). Hepatitis B vaccine is recommended for people who could be exposed to blood through needles or medical procedures, or body fluids during sexual intercourse with a new partner.

Soil- & Waterborne Infections

Leptospirosis

Leptospirosis is prevalent on the island; in 2020, 210 leptospirosis cases and 38 deaths were reported. Leptospira contamination can be attributed to climatic conditions (e.g., heavy rainfall, flooding) and to environmental factors, including agricultural practices, animal husbandry, inadequate disposal of waste, and poor sanitation. Travelers should avoid recreational activities in lakes and rivers, and other unprotected exposures to fresh water potentially contaminated with animal urine (see Sec. 5, Part 1, Ch. 10, Leptospirosis).

Schistosomiasis

Based on the results of a 2013 serological survey conducted in provinces with a history of schistosomiasis transmission, the Dominican Republic has likely eliminated schistosomiasis transmission. This status has not yet been verified according to World Health Organization (WHO) criteria.

Vectorborne Diseases

Vectorborne viral diseases (e.g., dengue), as well as parasitic diseases (e.g., malaria) are potential concerns for travelers to the Dominican Republic. All travelers should take precautions to prevent mosquito bites by wearing long-sleeved shirts and long pants and by using insect repellent (see Sec. 4, Ch. 6, Mosquitoes, Ticks & Other Arthropods).

Arboviruses: Chikungunya, Dengue & Zika

Dengue is widespread in the Dominican Republic; 3,964 cases and 38 deaths were reported in 2020. Although cases of dengue are reported year-round, transmission frequently increases during the rainy season, May–November. The principal mosquito vector of the dengue virus, Aedes aegypti, is found in both rural and urban areas in the Dominican Republic (see Sec. 5, Part 2, Ch. 4, Dengue). Neither chikungunya nor Zika have been detected in the Dominican Republic for several years.

Lymphatic Filariasis

The Dominican Republic is actively participating in the global program to eliminate lymphatic filariasis (LF). LF is considered endemic to some smaller foci in the east and southwest regions of the country. As of 2020, the country had achieved targets set by the WHO to stop annual treatment, suggesting low likelihood of ongoing disease transmission and minimal risk to travelers. The Dominican Republic is still working to achieve all targets demonstrating elimination of LF as a public health problem (see Sec. 5, Part 3, Ch. 9, Lymphatic Filariasis, and the WHO website.

Malaria

For the most up-to-date malaria prevention information for the Dominican Republic, please visit Yellow Fever Vaccine and Malaria Prevention Information, by Country.

Environmental Hazards & Risks

Animal Bites & Rabies

Reports of animal rabies in the Dominican Republic are not uncommon, and the last reported case of human rabies was in 2019. In 2020, no cases of animal rabies or human rabies were reported. Postexposure rabies prophylaxis is available in specialized and regional hospitals. Consider preexposure vaccination for travelers potentially at risk for animal bites (e.g., people spending extended time outdoors, anyone handling animals). Advise travelers to avoid petting or playing with animals.

Climate & Sun Exposure

Visitors to the Dominican Republic often underestimate the strength of the sun and the dehydrating effect of the humid environment. Encourage travelers to take precautions to avoid sunburn by wearing hats and suitable clothing, along with proper application of a broad-spectrum sunscreen with a sun protection factor (SPF) ≥15 that protects against both ultraviolet A and B (see Sec. 4, Ch. 1, Sun Exposure). Travelers should drink plenty of hydrating fluids throughout the day.

Toxic Exposures

Methanol

Poisonings from consuming methanol- contaminated ethanol in fermented beverages occur in both resort areas and in the community in the Dominican Republic. In December 2017, an outbreak involved 41 vacationers in the resort areas of Punta Cana. In December 2019, 4 people became sick and 2 died from methanol poisoning. In a community outbreak in November 2020, 9 men in the Santo Domingo Este municipality suffered methanol poisoning after consuming a contaminated drink. During January–April 2021, an outbreak involving >300 people, predominantly in the northern and northeastern regions of the country, was traced to drinking adulterated ethanol; >100 died. The majority of cases occurred the week after the long Easter weekend.

Safety & Security

Crime

The risk for crime in the Dominican Republic is like that of major cities in the United States. Although most crime affecting tourists involves robbery or pickpocketing, more serious assaults occasionally occur, and perpetrators might react violently if resisted (see Sec. 4, Ch. 11, Safety & Security Overseas). Visitors to the Dominican Republic should follow normal safety precautions (e.g., going out in groups, especially at night; using only licensed taxi drivers; drinking alcohol in moderation; and being cautious of strangers). Criminal activity often is higher during the Christmas and New Year season, and additional caution during that time is warranted.

Traffic-Related Injuries

Driving in the Dominican Republic is hazardous (see Sec. 8, Ch. 5, Road & Traffic Safety). Traffic laws are rarely enforced, and drivers commonly drive while intoxicated, text while driving, exceed speed limits, do not respect red lights or stop signs, and drive without seatbelts or helmets. According to WHO statistics, the Dominican Republic has the highest number of traffic deaths per capita in the world (110 per 100,000 population in 2019).

Many fatal or serious traffic crashes involve motorcycles and pedestrians. Motorcycle taxis, used throughout the country, including in tourist areas, frequently carry ≥2 passengers riding without helmets. Remind visitors to avoid motorcycle taxis, to use only licensed taxis, and to always wear a seatbelt.

Availability & Quality of Medical Care

In the Dominican Republic, public medical clinics lack basic resources and supplies, and few or no English-speaking staff are available. In addition, only minimal staff are available overnight in non-emergency wards; if hospitalized, travelers should consider hiring a private nurse to spend the night.

Private hospitals and doctors might offer a more comprehensive range of services but typically require advance payment or proof of adequate insurance before providing medical services or admitting a patient. Some hotels and resorts have preestablished, exclusive arrangements with select medical providers; these can have additional, associated costs, and might also limit choices for emergency medical care.

Psychological and psychiatric services are limited, even in the larger cities, with hospital-based care available only through government institutions.

Medical Tourism

The market for medical tourism, including plastic surgery and dental care, is growing in the Dominican Republic. Thousands of patients travel to the country each year to access medical services that cost a fraction of what they do in the United States. Several companies and clinics offer package deals that include postsurgical recovery at local tourist resorts. Most health care facilities catering to medical tourists have not, however, met the standards required by international accrediting bodies.

Some medical tourists to the Dominican Republic have experienced a substandard quality of care, health care–associated infections, and even death. Anyone considering the Dominican Republic as a destination for medical procedures should consult with a US health care provider before travel, and research whether the health care providers and facilities in the Dominican Republic meet accepted standards of care (see Sec. 6, Ch. 4, Medical Tourism). Legal options in case of malpractice are very limited in the Dominican Republic.

The following authors contributed to the previous version of this chapter: